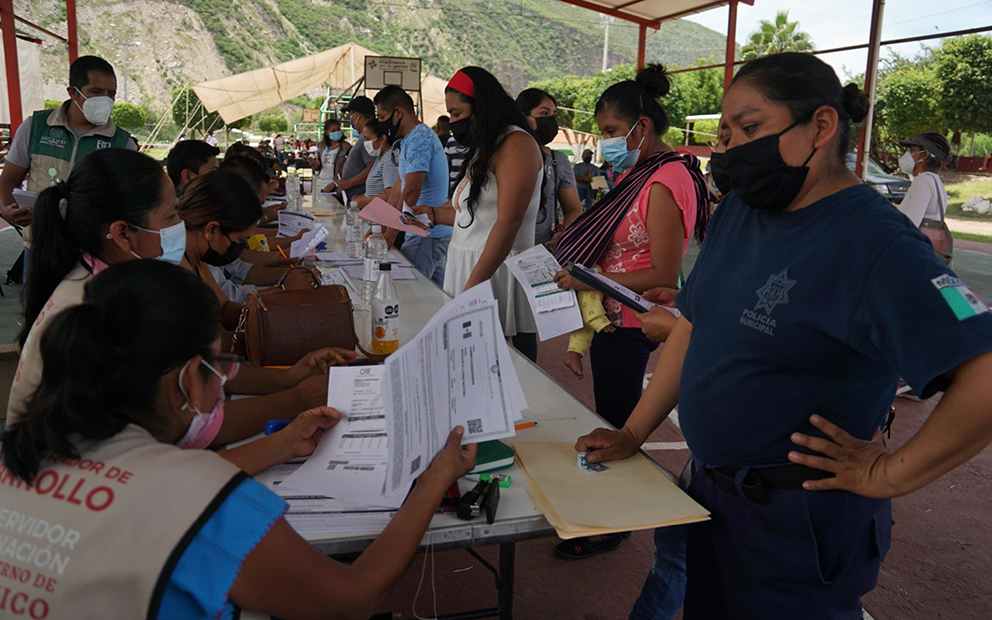

This week, vaccines returned to La Montaña, the poorest region in the state of Guerrero, with the largest Indigenous population. The objective is to vaccinate all adults over 18 in the state, one of the most abandoned in the country. In Tlapa, the economic center of this area, attendance was massive.

Text by Daniela Pastrana and Isabel Briseño, originally published July 25, 2021.

Photos by Isabel Briseño.

Translation by Dawn Marie Paley.

TLAPA, GUERRERO – Juana Ferino Tapia walks quickly, looking for a place to make photocopies. The woman, a 48 year old housewife, was already worried because here, in La Montaña, vaccines have only arrived for people over 50. Many didn’t get the vaccine out of distrust. But this week, the vaccines came back and now they are for everyone who was left out: the population between 18 and 49 years old. That’s why she’s hurrying to make the copies she needs to get her vaccine.

Like all the residents of the 19 municipalities of La Montaña, Juana and her husband are going to be inoculated with the Chinese vaccine CanSino, which is a single dose and therefore less logistically completed in this region, where there are few roads.

But it’s all the same to Juana, who doesn’t know the difference between the different vaccines that are being given in Mexico. When I asked her if she knows what vaccine she’s getting, she replied, smiling, “the Covid one.”

Unlike in February, when the vaccination of people over 60 kicked off in the remotest parts of México, the anti-vaccine campaigns from the center haven’t arrived here. On the contrary, the feeling here in Tlapa, the economic center of the region, is a kind of “vaccine energy.”

You can hear it among teachers and on the radio, like the pitch that Nacario de Jesús Chepe makes on Imparcial Radio on 99.1 fm. He reads an article from El Sol de Acapulco on the economic and psychological impacts of the pandemic out loud.

“Those who have lost family members must reflect. For youth, for everyone who has suffered the loss of family members, Covid 19 isn’t simply an illness, rather, it affects us economically and emotionally,” emphasized the broadcaster.

“I don’t know why many people don’t want to get vaccinated, they don’t want to use a mask, or do anything, because ‘God wanted it that way.’ Friends: I’m doing it. In other places they wish they had the vaccine and they don’t. That is taking place in other parts of Latin America. It’s an opportunity we have to take advantage of, since yesterday you can get a vaccine if you are over 18.”

Parallel realities

Quetzalli Rojas Villa, a 21 year old nursing student, is also looking for a place to make copies.

She said she became interested in nursing when her mother got sick and she looked after her. Her mother had diabetes and passed away two years ago from kidney failure.

Now, she has no doubts: “I want to get vaccinated to protect myself and my family members,” she said.

Her father was vaccinated in February, when the vaccine began to be administered to seniors. Her four brothers are teachers, they are also already vaccinated. Even so, Quetzalli doesn’t want to be a source of contagion to her family.

I asked her what she thinks, as a future nurse, about the CanSino vaccine, which her and her brothers will receive.

“It’s one of the best vaccines,” she said, without hesitation.

It’s paradoxical to think about these parallel realities. In France and other countries in Europe people who don’t want to get vaccinated are fighting the police because of restrictions the governments are bringing in so that they will take the vaccine. In this town, which doesn’t have a CAT scanner or an ultrasound machine in the hospital, people arrive from all around to line up for a vaccine. In México City, there is drama every time the authorities announce what vaccine will go to what new group, while in this majority Indigenous (Nahuas, Na Savi, Me ‘Phaa and Ñoomdá), which lacks doctors and medicine, people are grateful for whatever vaccine arrives.

Quetzalli, for example, studies in Puebla (250km away) because here, in La Montaña, there is no nursing school. She wants to come back to Tlapa to do her social service and then work in public health, helping sick people from the communities. But the path to doing so is as difficult as wanting to study nursing if you’re born in Tlapa.

For the health of our children

Guadalupe de la Cruz Trinidad is from Ahuacuotzingo, a population that is on the road to Chilapa, around 2.5 hours from here. She’s 29 and has three sons: Pedro Alexis, who is 9, Miriam, who is 5, and a four month old baby she hasn’t named yet.

She gave birth in the middle of the pandemic. She said that everything went fine in the Women’s Hospital, though she was sent to buy medicines elsewhere because there was none in the hospital. Even so, she said, it seemed like a better option than giving birth at home.

“I was hoping not to get it (Covid) in the hospital. Then I thought, ‘I can still be scared, but I should deliver in the hospital and not in my house and lose another one (she previously lost a baby for lack of access to medical care). In the hospital we were talking to the doctors, none of what they say about dying from the vaccine is true. But people say many things that are not true.”

Guadalupe said that in her town there are people who don’t want to get a vaccine, but she’s convinced that she has to do it, for the health of her children.

“I want to see my daughter healthy and strong. We have to get vaccinated so that this illness stops,” she said.

She explains her concern:

“My kids, more than anything, they don’t want to go out to avoid getting sick. I don’t go out, only to buy the things I need. But they don’t even want to go to school. They’re scared. Especially my son, who is older, he can already read and everything… We have to educate people to get vaccinated, to not be afraid, they know that we have to get vaccinated against illnesses. They have to go to school, it’s been too long. In our village there are people who say not to get vaccinated, but I think that in order to know you should try it, and, well, put our faith in God. I don’t think anything bad will happen.”

A few steps away, police officer Margarita Juárez Martín shares Guadalupe’s concerns. She is especially concerned that there is no vaccine for children.

She said she’s a little scared of the vaccine, but “the nurses we know tell us that we should get it.”

On Wednesday she asked for a day off to get vaccinated. She hasn’t heard anything about the vaccine she’ll get (CanSino). Not about the lack of transparency in the purchase, or of the safety and efficiency of the vaccine.

Like any good police officer, she said dryly: “I’m unaware of the issue.”

Any doubts about the vaccine?

More than 40 million Mexicans have received at least one dose of one of the six vaccines approved for emergency use. This represents about 45 per cent of the adult population nationwide. The states that are most advanced in the application of vaccines are Baja California Norte, Baja California Sur, and México City, with vaccination rates above 70 per cent.

Guerrero, on the other hand, has one of the lowest vaccination rates, together with Puebla and Chiapas, where just 30 percent of the population is vaccinated.

Here, too, there are differences. In four municipalities –Cualac, Alpoyeca, Huamuxtitlán and Xochihuehuetlán— so many people wanted to get vaccinated they had to send more doses. But in more marginalized municipalities, like Cochoapa, Metlatónoc, Acatepec and Tlacoapa it was necessary to add more vaccination days and organize brigades to bring vaccines into the communities.

The distrust in health institutions and the fear caused by rumors and social media campaigns were the key factors, in this region, that caused people to turn down the vaccine.

Now, the line-ups move forward more quickly and it’s much better organized.

Outside of the main vaccination center in Tlapa, Gaudencio Solano yells out instructions on how to fill out the vaccine registry to those who are lined up.

“If you are 36 years old, write 36. If you turn 37 tomorrow, don’t write that, you have to put your current age… Telephone, put your personal number… On the left side it asks for your email. If you have one, write it, otherwise leave it blank… Where it says address we’re going to take that from your proof of residence, with one difference, we’re going to change the postal code. You can see that your electricity bill still says 42300. Do you remember what Tlapa’s postal code is? 41 what? 41304. Very good! Then comes the part about medical conditions. There are two options: yes or no. If you have diabetes you mark yes, if not, obviously, don’t. For the women, if you’re pregnant mark yes, if you’re not, mark no… The lot number is A062621.. Remember that the only original that we’re keeping is the vaccination document, together with a copy of your voting card, your tax number, and your proof of residency. Everything up to date, please! Any questions?

“What if I’m breastfeeding,” asks a young woman.

“Go ahead,” says the man, and then, “just make sure you mention it to the doctors.”

“How many copies do you need?” asks another man.

“Fortunately it’s been like this since yesterday, we’re seeing 2,800 to 3,200 people every day. We are supposed to give doses to 20,000 people,” he tells us in a moment of calm.

“Is that more than last time?”

“Many more”

“What is the main thing people ask you? What’s their main concern?”

“The most common question is what brand the vaccine is, or the lot number.”

“Nobody distrusts this vaccine?”

“Not yet, thankfully.”

“The anti-vaccine campaign hasn’t arrived here?”

“Yes, among older people. Younger people, they have more information about the new wave, and there is no issue.”

“Were you already vaccinated?”

“Yes, with CanSino.”

“Are you worried about what is being said about that vaccine? Or that they won’t let you into Europe?”

“What can I say,” he said, smiling, and looked around. “There are two different worlds. What we aspire to here is to go to Puebla or Mexico (City), or if we want to go really far, to Monterrey.”

Daniela Pastrana wanted to be an explorer and see the world, but instead she became a journalist and decided to try and understand human societies. For six years she ran the Red de Periodistas de a Pie. She founded Pie de Página, a digital outlet that seeks to change the narrative of terror that is installed in the Mexican media. She always has more questions than answers.

Isabel Briceño has never liked the fact that happy stories come to an end, which is why she captures them on camera, she captures sad stories in a search for answers.

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona