From Palestine to the Lacandon Jungle, in this time of wars that we live in, the peoples put forward the possibilities for resurgence, rebirth, resistance, rooting and germination of life in the stones and ruins left by genocide and narco-violence in the world

By Daliri Oropeza Alvarez

I learned what Hakura is in Palestine, thanks to Natasha Aruri. She is a tall woman in comparison to the average height that we are in Mexico. From the moment I saw her I felt a lot of affinity for the way she smiles. I met her at the meeting Fertile territories: towards a lexicon of land struggles, held in Cuetzalan.

The Hakura, Natasha explains, is a place in the house where families have a space to plant and keep supplies and tools for daily life. It is essential in the creation of community because they are open spaces where children can play or there are paths for the inhabitants, for example, of Jerusalem, where she was born. A space to connect the community. “Disconnected we are more vulnerable,” she says.

It was unavoidable for me to approach her after she introduced herself. I ask her about the context of the Israeli attacks. I took it as an great opportunity that we had met at the meeting held by the Sabr Collective, during the visit of several people to Mexico as part of the International Conference of Critical Geographies. The conference was previously held in Palestine and then Greece.

“Dignity!” she says to me with emotion. That is the main demand of the Palestinian people.

“Dignity, and that they stop questioning our humanity. We are not ‘barbaric animals’ as Israeli and Western leaders have tried to label us, dehumanize us… We want to be recognized as equal human beings who feel pain and want nothing more than to have a decent life… Dignity, therefore, is our land. May we not be discarded or expelled from her…. Without land, which is our home, there can be no dignity,” Natasha assures us in English, the language in which we communicate.

The land that is home, I think as I say it. During the meeting, participants from Chiapas, Oaxaca, Puebla, CDMX, Brazil, Egypt, Palestine or the US talk about territories and struggles for land, what they have meant in their own lands or homes, and the words they want to share.

I think of Natasha’s own story, who confides in me that she studied for a degree in Architecture during the so-called second intifada, which was very bloody, between 2001 and 2006 at Birzeit University, a municipality in Palestine, located in the West Bank, in the province of Ramallah and Al Bireh.

In 2008 she studied her master and PhD in urban planning and researched how to remake city infrastructures (physical and social) to germinate the emergence of new and better forms of resistance against oppression and dispossession. She left Palestine for graduate school and upon her return, Israel has denied her entry several times, only complicating the process of family reunification.

In the discussion, the category with which they define what is happening in Palestine is Settler Colonialism or Settlement Colonialism. They also use the category genocide. Not to be outdone, Israel’s bloody bombardments have already killed… they are not numbers, they are humans. Many are children. 5 thousand 87 people, among them 2 thousand 55 minors, 1 thousand 119 women and 15 thousand 273 wounded. More than 1,500 missing in the rubble.

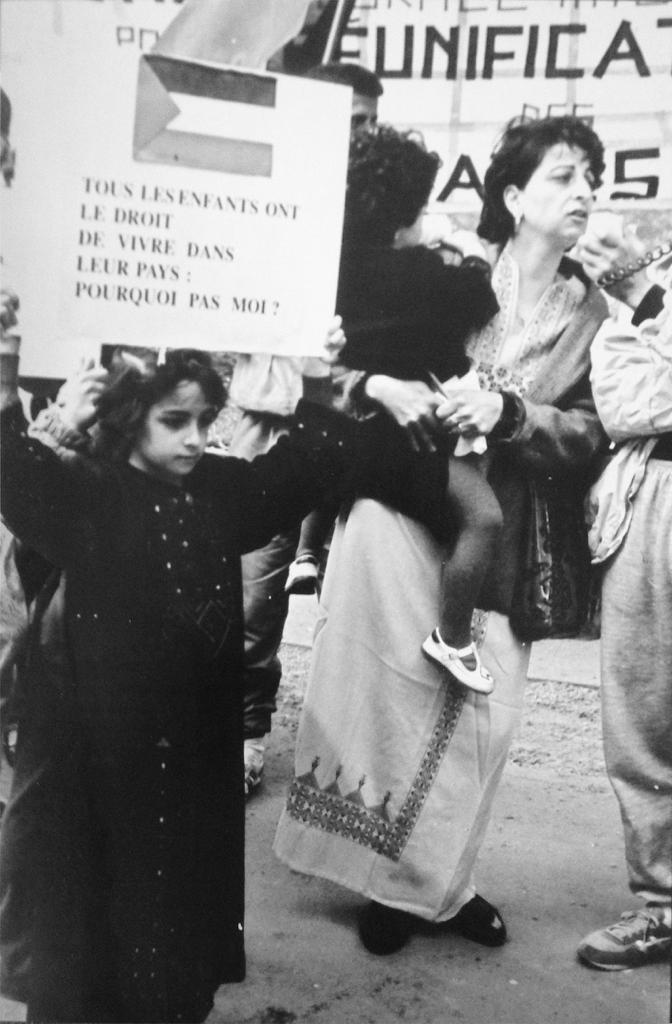

Even with the bombings, Natasha Aruri does not lose hope of returning to her homeland. In the photo, she marches as a child with her family and the poster she is holding asks: “All children have the right to live in their country, why not me?”

I think of the defenders of territory in Mexico who have had to leave their communities and always think about returning. Professor Jorge Velázquez, defender of the Nahua community of Amilcingo who had to leave because of persecution. Or Esteban and Clementina, church authorities of the Yaqui Tribe who had to leave because of harassment and crime in their communities. And they always think about returning. They among so many others.

This is where the Hakura, an Arabic word, makes sense as a physical space of resistance in Palestine. A tool of the Palestinian people to procure the region’s own plants, such as olive trees. To procure coexistence and organization from the family nucleus.

“Sadly we have no power or political influence to fight against genocide, as can be seen in the attitudes of governments. The only tool we have is solidarity,” describes the Palestinian architect.

I think that recently, the U kúuchil k Ch’i’ibalo’on Community Center launched a campaign against the genocide of the Mayan people. For this collective school of Chan Santa Cruz, it is important to state that there has been a war against the peninsular Maya people since colonial times, throughout the modern era of Porfirio Díaz, and arriving now at the poorly-named “Mayan” train that AMLO’s government is building.

It is a word that does not have a strong resonance in Mexico, but it frames different atrocities that are still in full force. And now they sweep through with megaprojects, co-optation of people through social programs, militarization or with the impunity that prevails in the face of organized crime, drug trafficking, et al.

I think of news for children that they make so that children are aware of the devastation of the Mayan jungle, thinking about the survival and future of the people, land, water and people. I think of the similarity between the Mayan solar and the Hakura.

Natasha Aruri describes it as solidarity on several levels: “standing in solidarity with each other as Palestinians, helping each other to move forward despite the destruction and pain…”

“Nothing in the world can erase the pain and trauma of the children of Gaza who have lived through several genocidal attacks by Israel in recent years (similarly, the children in Israeli prisons who are being subjected to horrors and torture)….. But we must keep trying… in spite of the very few resources we have…. We cannot give up…”.

I think of the writing left by the poet Heba Abu Nada before she was assassinated:

The night in the city is dark,

except for the glow of the

missiles;

silent, except for the

sound of bombing;

terrifying, except for the

soothing promise of

prayer;

black, except for the light of the

martyrs.

Hope lies in the exception.

“The second cornerstone on which our struggle against genocide is sustained is the solidarity of the peoples of the world with us, internationalist solidarity.”

I think of the Zapatista Crossing to Europe carried out by two delegations (air and sea) of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in 2020, at the height of the pandemic, in the same year that marked the 500th anniversary of the fall of Tenochtitlan.

“This dimension of solidarity used to be much stronger in the 1960s and 1980s. The “Oslo Era” destroyed many of the “bases” we used to have (also the changes of other societies’ struggles in the post-Cold War era). But, we are hopeful that our generation can reverse the tide… there are some signs that give hope, like you… for this, meetings, fostering common dreams and projects are very important…,” Natasha tells me while in my mind it resonates: common dreams.

Common horizons between peoples.

With the passage of generations, the attacks have changed their ways and means; the genocide in Quintana Roo has adapted to the contemporary conditions. The perpetration of attempts on the lives of the Mayan people, and the population in general, have not ceased; the present exploitation and dispossesion have intensified endlessly: the impoverishment, the contamination of the water and foods, the premature deaths due to violence and insecurity, territorial reorganization, militarization, the extermination of ways of life… Because of this, in these critical times, we should not forget the attempted genocide in Dzulá, which, remembering year after year, remains firm in the memory of the Máasewal people. Cultivating memory so that the injustices are never again repeated; thus recovering the resistance and the defense of territory and autonomy.

90 years ago, at dawn on the 13th of April 1933, soldiers of the federal army attacked the people of Dzulá, in another devastating episode of genocide against the Máasewal Maya people. The objective was to carry out the extermination of indigenous autonomy, the colonization of the territory and the imposition of Mexican education and culture. The Maya resisted and defended their community with courage, as they had so many times, but the difference in their weapons could not combat murders, looting, and devastation. With the town surrounded, exile into the jungle was the only escape for six years.

The power of a poem can expose and exalt the depths of being in a world full of grievances that do not cease.

The EZLN brings to the present the poem, The Motives of the Wolf by Nicaraguan writer Rubén Darío, 110 years after its creation. They publish it in the context of the narco‘s infiltration into the depths of the Lacandon Jungle. The place where the high school teacher José Artemio López Aguilar was assassinated. He coordinated the March for Peace last October 12 in Chicomuselo, where the dispute between cartels for territory has escalated.

But then I began to see that in all the housesthere was envy, anger and wrath,and in all the faces burned the embers of hatred.of hatred, of lust, of infamy and lies.Brothers waged war against brothers,the weak lost, the wicked won,female and male were like dog and bitch,and one fine day they all beat me up.They saw me humble, I licked their handsand feet. I followed your sacred laws,all creatures were my brothers:brothers men, brothers oxen,sister stars and brother worms.And thus, they beat me and cast me out.And their laughter was like boiling water,and within my guts revived the beast,and I felt like a bad wolf all of a sudden;but always better than those bad people.And I began to fight again here,to defend myself and to feed myself.As the bear does, as the wild boar does,that to live, have to kill.

The tools of liberation are seen as a weapon. The wolf as a being that is always evil. The wolf that all living beings carry inside. The weapons that the peoples have to seek justice, to put a stop to extermination, to genocide, to dispossession. I think of the armed uprising of 1994.

Let us not forget the way in which 43 towns in Guerrero (and counting) armed themselves to put a stop to organized crime recently. This history is also present in towns like Cherán1, and Óstula 2in Michoacán.

Circumstances are leading more and more people to take justice into their own hands. I can’t help but think of the recent criminalization of the Otomí ñathö people of Huitzizilapan for having stopped criminals in their community in the Otomí Forest.

The people of Huitzizilapan got fed up with the assailants and extortionists. The people reacted and organized themselves to carry out a process of their own justice. Now, the villagers are being accused of a crime they did not commit.

The peoples of the world have taught us that they have different weapons to confront oppression, invasion and extermination. One of them is the exercise of autonomy. Another is the arts, sciences, and philosophies. Another weapon that has been crucial is the alliance amongst the peoples of the world. That weapon of multi-affinities.

Original text published in Pie de Pagina on October 24, 2023. https://piedepagina.mx/las-resistencias-de-los-pueblos/

English translation by Schools for Chiapas.

Botas llenas de Tierra. Tejedora de relatos. Narro sublevaciones, grietas, sanaciones, Pueblos. #CaminamosPreguntando De oficio, periodista. Maestra en Comunicación y cambio social. #Edición #Crónica #Foto #Investigación

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona