Vaccinating 100 million people is a good tale to begin with, but to do so while prioritizing the most vulnerable is something we may never see again. We’ll follow this historic campaign from the Mountains of Guerrero to the urban áreas of the Valley of Mexico and the deserts of Baja California

Photos: Isabel Briseño, Duilio Rodríguez, María Ruiz

Text: Daniela Pastrana, originally published March 7, 2021

Translation: Dawn Marie Paley

MEXICO CITY–The second phase of vaccination in Mexico started with the forgotten: elders, Indigenous people, the poor, those who live in the most isolated communities or in densely populated urban peripheries. It is a historical exercise in social justice. And according to authorities, it is a strategy that will allow for a more rapid slowdown in the spread of the virus that just marked its first year in the country.

The worst pandemic in a century has killed at least 185,000 people in Mexico. The hope today is in vaccines, which began to be applied among seniors on February 15th (the first phase was applied to medical workers).

The goal of vaccinating more than 100 million people over the coming months is not minor, considering that the largest previous vaccination campaign carried out in Mexico up until today was 10 times smaller.

At Pie de Pagina we are documenting the beginning of this vaccination campaign in the parts of the country where the poorest, the most remote, the more peripheral communities live. These are postcards from our coverage in three of these places.

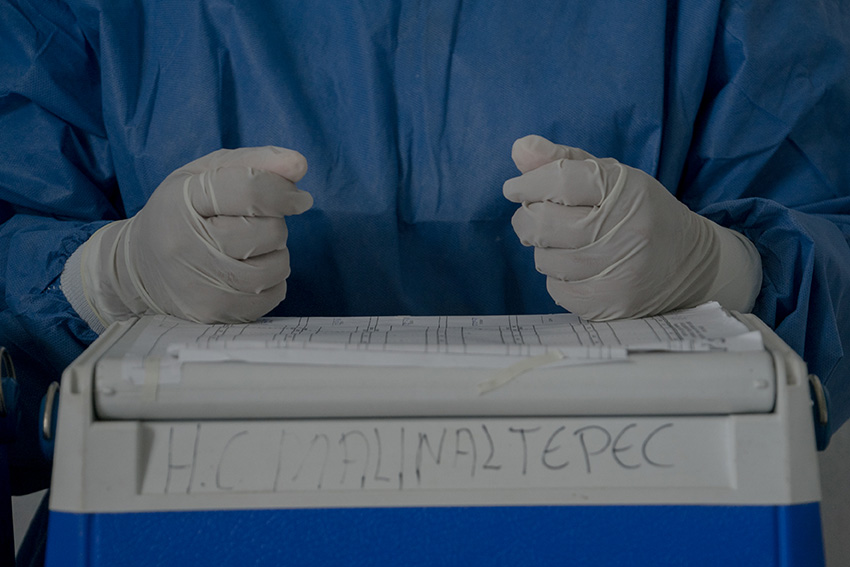

1. The Montaña in Guerrero and the disbelief of the marginalized

The Montaña in Guerrero is the most populated of all of the marginal areas in Mexico: 300,000 people live in its 19 municipalities, most of them Indigenous Nahua, Me’phaa and Ñomndáa peoples. Every year since Mexico began measuring poverty, this region has the most maternal deaths, school dropouts and child malnutrition. People survive based on what migration allows, be it to the farms of Sonora, Sinaloa or Baja California, or to the United States. But death is so common that the undercount of Covid deaths would be one of the highest in the country. Seventeen thousand doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine arrived in the region but the volunteers were faced with a problem: the disbelief of the population that has never received anything good from the government.

Photos: Isabel Briceño.

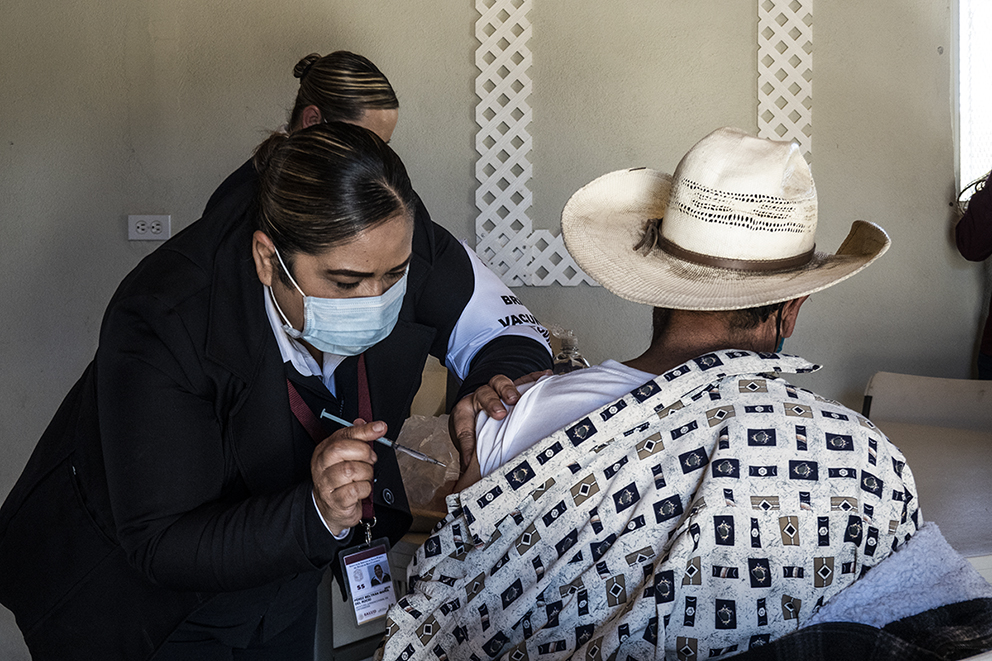

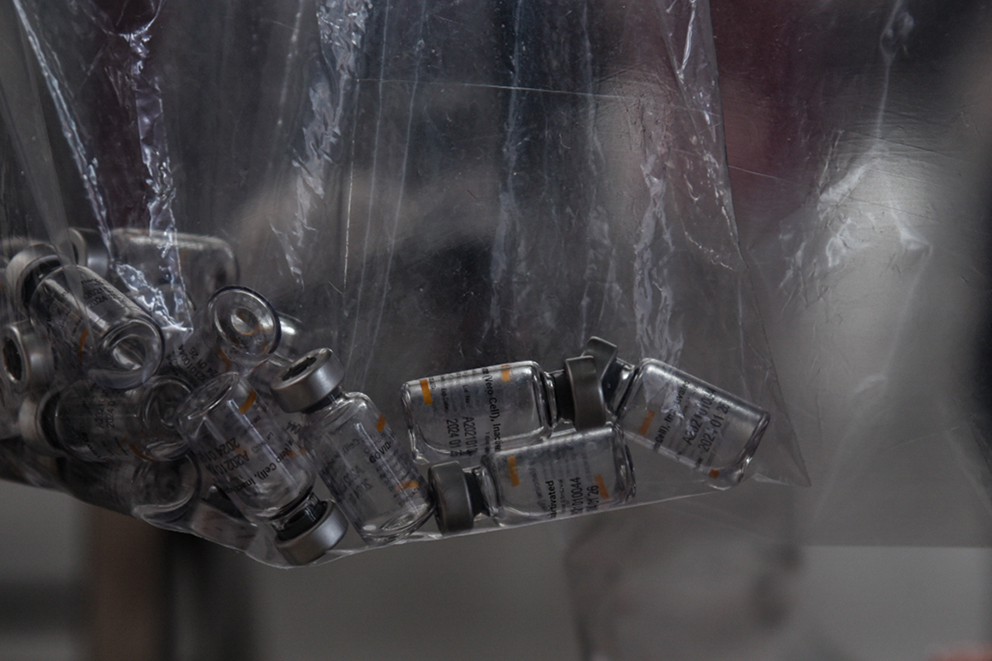

2. Ejido Kiliwas: the vaccines that arrived from India to the desert of Baja California

The Kiliwas are one of five Yumano-Cochimíe nations that live in the peninsula of Baja California and which, according to authorities, are in extreme risk of extinction. They live in ranches spread around in an ejido in Ensenada near the Trinidad Valley. There is not enough water in the ejido, just a few years ago a well was drilled that barely meets the needs of residents. Electricity arrived in 2000, and just a few months ago, those who were able to pay were connected to the internet. There’s no phones at all. After over two weeks in transit over more than 19,000km, the AstraZeneca vaccines that came from India arrived at the homes of every member of the ejido over 60 years old, to immunize the 13 Kiliwa elders left in Mexico.

Photos: Duilio Rodríguez.

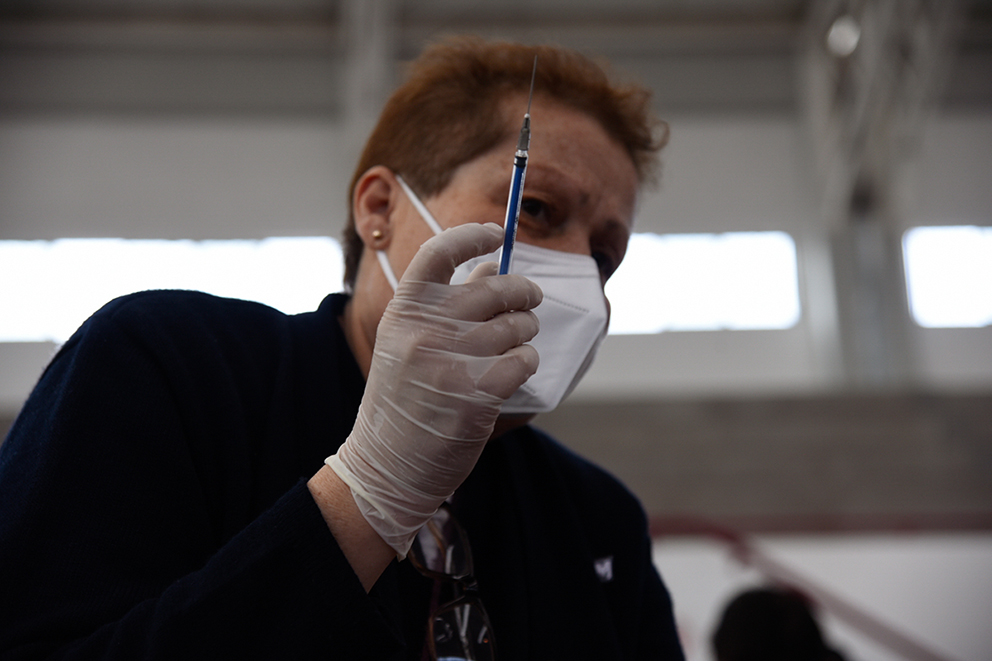

3. Ecatepec and the chaos of mega vaccination

Ecatepec is the most populous municipality in Mexico State and in the country. It is also one of the most marginalized and the first in urban poverty. It borders the north of Mexico City, and has the largest day-to-day population flow. This is where massive vaccination got its start, with the Sinovac vaccines from China. But demand overflowed the operation. Lineups at the vaccination sites were the hallmark of the first week of massive COVID-19 vaccine applications in the Valley of Mexico. Ecatepec was at the center of the disaster, where disinformation and fear of losing a chance to be vaccinated provoked three days of chaos. The challenge of giving out doses made the brigades of nurses into unstoppable vaccination machines.

Fotos: María Fernanda Ruíz.

Isabel Briceño has never liked the fact that happy stories come to an end, which is why she captures them on camera, she captures sad stories in a search for answers.

Duilio Rodriguez is a photographer and editor interested in art, ciname, arquitecture, literature, rock climbing and spots in general (except soccer). duiliorodriguez.com

María Fernanda Ruiz is always an outsider, audiovisual is her jam, and journalism is the path through which she understands and questions the world.

Daniela Pastrana wanted to be an explorer and see the world, but instead she became a journalist and decided to try and understand human societies. For six years she ran the Red de Periodistas de a Pie. She founded Pie de Página, a digital outlet that seeks to change the narrative of terror that is installed in the Mexican media. She always has more questions than answers.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona