At least 114 Indigenous migrants from Mexico died of COVID-19 in the United States last year: Nahuas, Otomís, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, Mazahuas, Huichols, Tepehuáns, Rarámuris, Purépechas and Triquis. Although they’ve been returned to their home country, they don’t always appear in consular data.

Text by Patricia Monreal, Mariana Morales, Alma Ríos, Teresa Montaño for La Verdad de Juarez, originally published on November 22, 2021.

Photo by Mariana Morales.

Translated by Elysse DaVega for Pie de Página in English.

It was the first week of July last year when a vehicle came to a sudden stop in the highlands of Chiapas. Its mission: to deliver the ashes of a Tzotzil woman who had passed away from COVID-19 just a month before, in a foreign land.

After a more than 3,000 kilometer journey from Alabama, the state where she lost her life to the virus that has devastated the world, Micaela –whose name has been changed– came home as ashes.

The car would return to Puschen, a neighborhood whose residents are natives of the municipality of San Juan Chamula. They’ve become accustomed to receiving the remains of deceased loved ones after passing away in or on the way to the U.S.

So many of their compatriots die there. The families, who only speak Tzotzil and have no internet access, anguish as they hurry to bury their loved ones according to their rituals and customs. This is why they’ve turned to Víctor Gómez, an Indigenous ex-migrant fluent in Spanish and English who began to explain to them what to do to bring the bodies home.

This information is available in Spanish on the Mexican government’s Foreign Affairs website, but not in any Indigenous languages. In its Chiapas office, as well as in the rest of México, there are no interpreters.

Micaela’s body surrendered on June 7, 2020, after a week of headaches, vomiting, fatigue, and loss of appetite. She didn’t see a doctor because she feared she would be deported.

She knew that the health crisis wouldn’t stop her from being persecuted. Foreign Affairs statistics confirm her fears: in 2020, 1,277 Indigenous women were deported, mainly hailing from Guerrero, Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Veracruz.

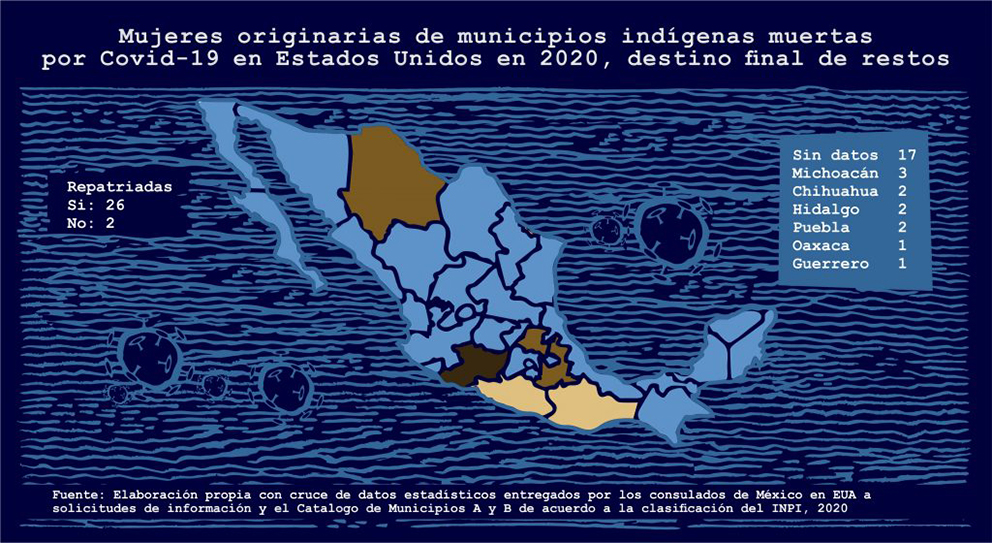

Upon cross-examination, we identified 28 Indigenous migrants that died of COVID-19 in the US: Nahuas, Otomís, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, Mazahuas, Huichols, Tepehuáns, Rarámuris, Purépechas, and Triquis.

But Micaela’s death –like many others– doesn’t appear in the Mexican government’s records.

The database, constructed from 1,007 records from municipal, state, and federal authorities, gives a rough estimate of the Indigenous people that died from COVID-19 in the US in 2020, how they dealt with the illness, and Mexico’s inaction to return their remains.

The Foreign Affairs records aren’t enough to create the full picture. There is a lack of transparency that extends to 27 states, including those with the largest Indigenous populations, such as Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Yucatán.

Mexico’s National Migration Institute, the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples, and the federal Secretary of Health are lacking in information or stated that they have none.

Our investigation found Guerrero is the only state that tracks what happened to its deceased migrants, but it’s records don’t match those of the 51 Mexican consulates in the U.S.

The 21 Indigenous people returned to Olinalá, Alcozauca, Alpoyeca, Atlamajalcingo del Monte, Copanatoyac, Malinaltepec, Tlapa de Comonfort, and Xalpatlahuac –all in Guerrero– don’t appear in consular data.

What’s worse is that cases like Micaela’s add up in places like Los Nogales, a community in Michoacán, where four [out of five] repatriated bodies are nonexistent in federal records.

«This is the case of Ms. Ofelia, Doña Soledad, Doña Chole, Doña Raquel and Mr. José Luis. They all died last year in the U.S. from COVID-19 and they were brought here to be buried,» says Rogelio Cerna Ortega, a communal authority from Los Nogales.

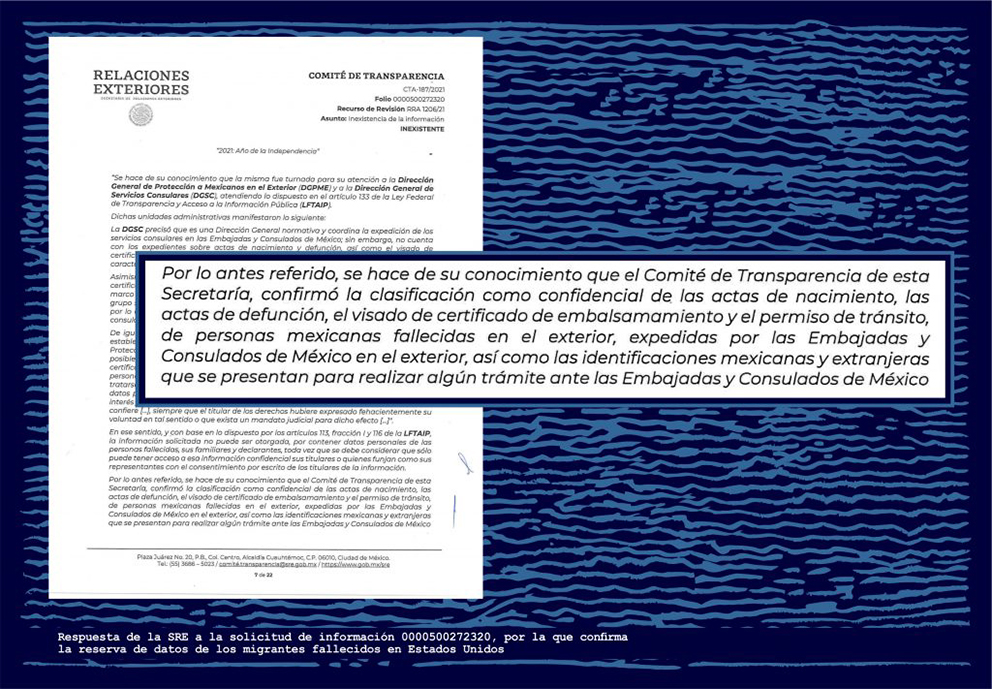

The road to discovering the final resting places of the deceased women in Mexico is a closed one. Foreign Affairs classified their birth and death certificates, visas, embalming certificates, and transit permits, which would have indicated where their coffins and urns were headed, as confidential.

«To die» in Tzotzil

When the world imposed new health guidelines to prevent the spread of COVID-19, Micaela went to work at a frozen food factory in Alabama; she continued the work to support her husband and her three children until she died. Micaela’s widower delivered the bad news to her mother over the phone in Tzotzil, their native language.

Aside from Micaela, who died at home, there’s another Indigenous person who, at age 55, died from the virus at her residence in San José, California. She was originally from Jaltocan, Hidalgo. Another 11 died at the hospital, the circumstances of deaths of 16 others are unknown.

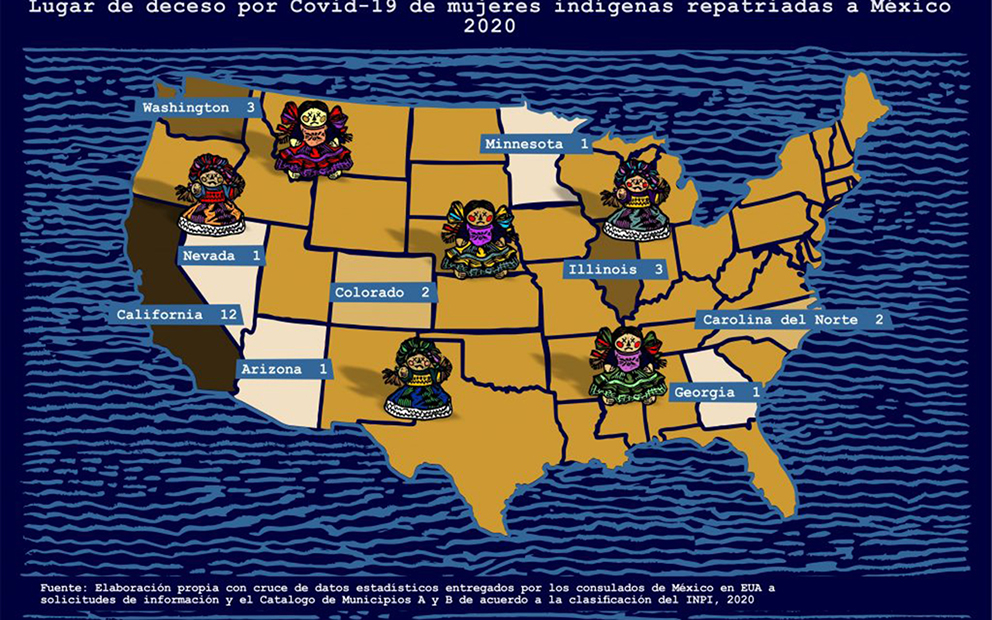

The deaths occurred in California, Illinois, Washington, North Carolina, Colorado, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Nevada, Georgia, and Arizona.

Micaela died in the state of Alabama, her family says.

Over the phone, the consulate told her brother –the only Spanish-speaker in the family– that they had to wait for her return, because the morgues were full of dead migrants. In Mexico, however, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador bragged that Foreign Affairs was effectively working to repatriate the bodies.

A posthumous pilgrimage

After five months of the pandemic in the United States, New York’s morgues and funeral homes were at capacity, and 709 Mexican families had sought consular support all over the country to repatriate their deceased, out of fear they would be buried in a mass grave.

Over that first year, an Indigenous person from Mexico died from the virus every three days in the US. Our investigation detected 114 deaths in federal records.

«In that situation, when were we going to be able to bring her home?» Micaela’s brother recalls.

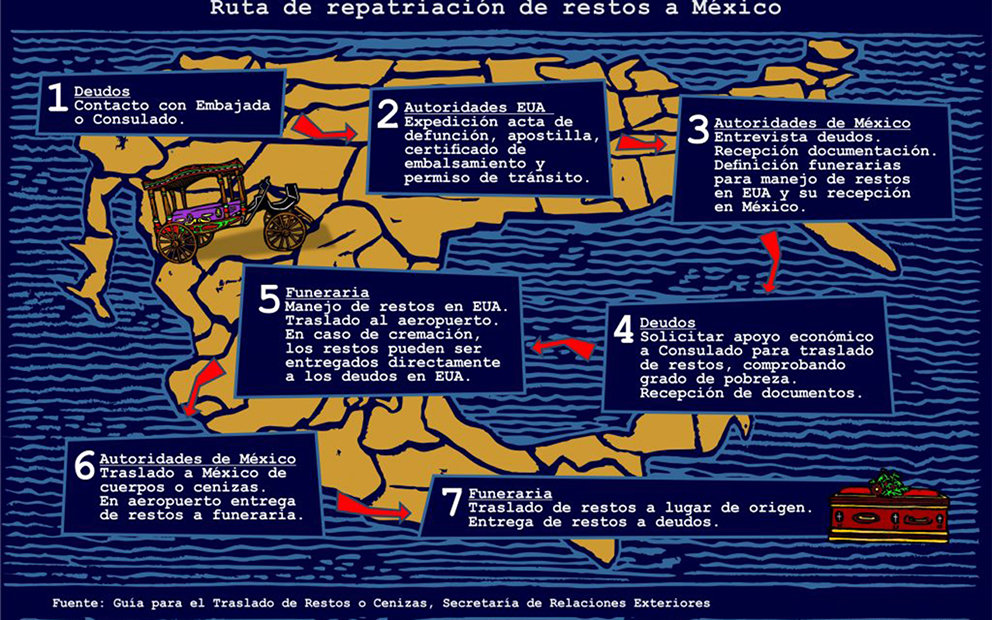

To officially bring the Tzotzil woman home, her family in the U.S. had to reach out to local authorities to obtain her death certificate and its apostille, the embalming certificate, and the transit permit. The pilgrimage didn’t end there: these documents had to be delivered to the consulate, which would certify and return them.

To obtain financial support, the paperwork increases; a request has to be sent to the consulate. If the consulate approves the request, it sends the financial aid to funeral homes, not the families.

Micaela’s husband was paralyzed by the fear that he might be deported, and that they wouldn’t understand Tzotzil, his native tongue. Because of this, his brother-in-law took charge and told him what he should do.

«Dying in the U.S. is expensive,» says María Fernanda Zavala, the former chief of the Migration Secretary’s Department of Human Rights and Repatriation in the state of Michoacán.

What she’s referring to is the fact that, on average, it costs $125,000 pesos (around US $6,000) to repatriate an entire body, and $30,000 to $40,000 pesos (US $1,400 to $1,800) to repatriate ashes. Because of this, there are some people who sell their belongings or collect donations.

«There’s no way that Indigenous peoples would allow for their relatives to be buried away from their land,» says Juan Lorenzo, a Mixe man from Oaxaca currently living in Pennsylvania.

Micaela’s family didn’t benefit from the money that the consulate gives to funeral homes. They didn’t even know about it because nobody told them –not in Spanish, and much less in their native Tzotzil.

Her ashes arrived in a car. Two friends, who work in sales and who come and go regularly, helped to transport them. The townspeople were stunned, they’re used to bidding farewell to their deceased whole, not as dust.

From the total of Indigenous women repatriated to Mexico, 13 arrived in coffins and nine arrived cremated. Three were Nahua, two Zapotec, two Otomí, one Mazahua, and another Tepehuán. There are six women for whom the status of their remains are unknown.

The highest number of deaths were among women aged 65 and up: 13 in total. There are nine Indigenous women aged 42 to 59, and five young people aged 23 to 36, just like Micaela. In one woman’s case, her age was unknown.

Ashes in a coffin

Micaela, the chattiest of five siblings, grew up just a few miles from her community’s mythical, colorful cemetery, El Romerillo.

Her father, a humble carpenter, and her mother María, a modest homemaker, watched sadly as she immigrated to the United States at just 14 years old. She left so they could rebuild their wooden house out of cement. Years later, to the same house that she left, she returned in ashes. She was able to return, but the bodies of two Indigenous people –one Triqui and one Mixtec woman from Oaxaca– could not. The remaining 26 returned to their final resting places of Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla, Hidalgo, Chihuahua, and Michoacán.

The ordeal gets more complicated with the transfer time: the transfers from the morgue, to a funeral home, then to Mexican territory, take four to six weeks. «There is way too much paperwork,» Fernanda Zavala explains.

In some cases it takes even longer. Gabriel Laguna’s family couldn’t hold a wake for him in his home in Tonatico, Mexico State, because a month and a week after he was hit by a car in California, his remains arrived «in an advanced state of decomposition.»

His relatives blame the funeral home and the airline for not handling the body properly, which prevented them from being able to see Gabriel and say goodbye before burying him.

In general, when migrants’ bodies arrive in Mexico, the services are handled by local funeral homes that the families hire; these funeral homes pick up the remains at airports and transfer them to the appropriate place.

In case of ashes, they can be sent in a diplomatic pouch to Foreign Affairs’ state offices, where relatives may pick them up, or, in Micaela’s case, receive them in US territory and determine their resting place from there.

Mexican families did the impossible to return their deceased: out of 114 Indigenous people, only nine never returned to their land.

«What can we do about it? It’s always been like this,» Micaela’s brother said in their family home, which, thanks to the Tzotzil woman’s hard work, is now made of cement.

In the absence of her body, the family put her ashes and traditional clothing in a wooden coffin in accordance with Tzotzil burial rites.

Today, Micaela rests in the Romerillo cemetery, where, decades before, she would run with her little sister, looking up at the sky and breathing in the earth’s humid smell. This is where people have grown accustomed to repatriating their dead migrant relatives.

This journalistic investigation was supported by the Adelante Reporting Initiative of the International Women’s Media Foundation. The translation above is of the first of a three part series.

This report was originally published by LA VERDAD, which is part of the Media Alliance organized by Red de Periodistas de a Pie. You can read the original here.

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona