Tlacoapa’s hospital has new equipment, but is without doctors or basic medicine

20 agosto, 2021

The first hospital that was built for residents of Tlacoapa, Guerrero, nearly collapsed due to flooding related to hurricanes. Then, US$3.5 million was spent on another hospital that was never inaugurated. Now it is open, but there’s no doctors. In one of the most abandoned municipalities in Mexico, access to health remains a distant promise.

Text by José Ignacio De Alba, originally published August 5, 2021.

Photos by Isabel Briseño.

Translation by Dawn Marie Paley.

TLACOAPA, GUERRERO–The residents of Tlacoapa, in Guerrero’s La Montaña region, waited eight years for the federal government to provide them with a hospital. The federal government finally did… and now, there are no doctors or specialists to attend to the population.

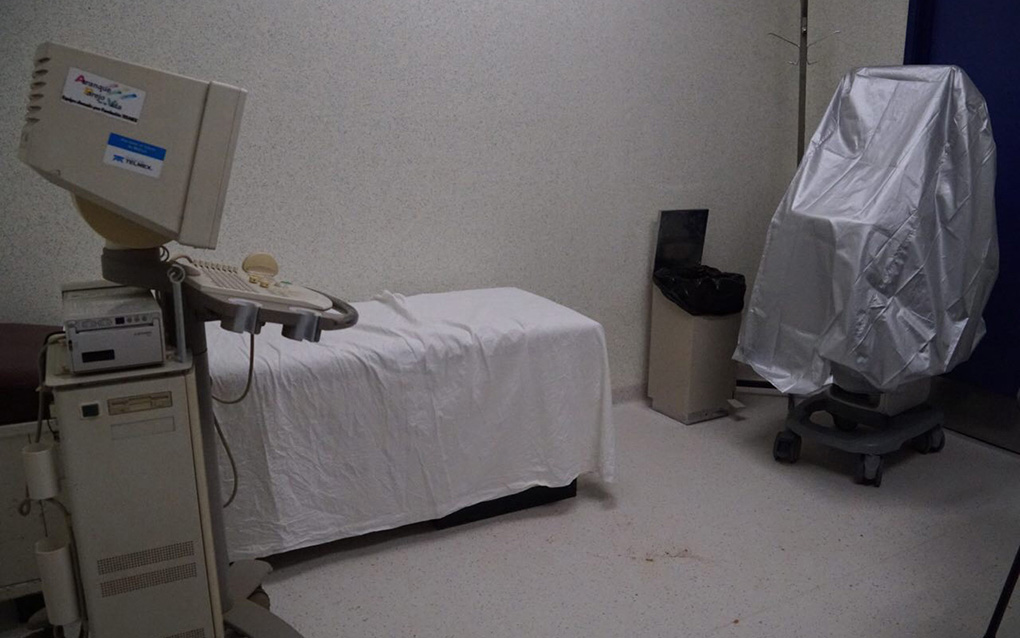

The hospital that opened its doors two weeks ago, in the most abandoned municipality in one of the most marginalized parts of Mexico is one of the best equipped in the region. It has dental offices, preventative medicine, gynecology, pediatrics, a recovery area, six hospital beds, a delivery room, an x-ray laboratory, an ultrasound, a clinical laboratory, an emergency room, a surgery room, a postoperative recovery room, an all purpose room, areas for medical residents and administrative offices. What it doesn’t have is a surgeon, an anesthesiologist, a gynecologist, a dentist, a radiologist, a psychologist or a pediatric doctor. Nor is there someone who can translate to the Me’phaa or Náhuatl languages, which is what is spoken in the communities of this municipality.

The building, which even has an elevator –possibly the only elevator in Guerrero’s La Montaña region– stands out like a huge white elephant, a symbol of the theft, corruption and ill treatment of the poorest people in Mexico.

This is its story.

A $3.2 million dollar “reconstruction”

In September of 2013, tropical storms Ingrid and Manuel hit this region of Guerrero. Perhaps in other parts of the country the impacts would have been less severe, but here, where there are no roads and people live in precarious houses on steep slopes, the storms caused a true humanitarian crisis. There were mudslides that destroyed communities, swelling rivers cut various towns off, and harvests were ruined.

The impacts led to what the government of Enrique Peña Nieto called “rescue operations to make the population safe.” In addition, a mega-investment of $3.2 million dollars was announced for the La Montaña region. The federal program would uplift this area, historically ignored by the government. The Secretariat of Social Development (today the Secretariat of Wellbeing), then overseen by Rosario Robles, took charge of managing the New Plan for Guerrero.

Rosario Robles traveled to Tlacoapa in April, 2014, “on instructions from President Enrique Peña Nieto,” to announce that the investment in the municipality would be so large that it would end up “better than it was before Ingrid and Manuel.”

In the auditorium near the main city hall, the official made various promises, together with the General Secretary of the Government of Guerrero, Jesús Martínez Garnelo; the coordinator of the Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples, Nuvia Mayorga; Tlacoapa’s mayor Efrén Merino Sierra; the federal sub-secretary of Community Development and Social Participation, Javier Guerrero García; and the state delegate of the Development Secretariat (SEDESOL) José Manuel Armenta Tello.

Robles announced, among other things, that loans for starting productive projects would be granted, that scholarships for youth all the way up to university would be expanded, that the Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples would build 20km of highway, which would mean that Tlacoapa would stop being the only municipality in La Montaña without a paved road. It was also announced that the two schools in Tlacoapa would be relocated, that the Secretariat of Agrarian Development would build hundreds of houses, and that the Secretariat of Communications and Transport would build new bridges.

Finally, Robles said: “…in the same way, we have been informed by the state government, and now we are going to supervise the area where the health center will be built, we know this is a pressing need. We know that now they are located in a temporary way in an area that belongs to the municipal commission. But we have to build a new health center, because that is what has been decided by the CENAPRED [National Disaster Prevention Center].”

In the same speech, Robles pointed to the mayor’s role. “Today, Mr. Mayor, we need you to make the commitment and outline the process for the immediate construction of the hospital. On the part of the federal government there is money for this hospital to be built immediately.”

Robles travelled at least twice to Tlacoapa, where she personally supervised the building of various buildings in the municipality.

But the hospital was never inaugurated. In February of this year, when a team from Pie de Página arrived in the community to report on the vaccine rollout, nurses and a doctor were still working in the House of Communal Goods, which, after the tragic storms, had been used as an improvised hospital.

Eight years later, Rosario Robles is in prison, accused of corruption unrelated to her activities in Guerrero. The rest of the officials that promised to rebuild Tlacoapa after the hurricane no longer show their faces in the area.

Today, Tlacoapa remains one of the municipalities with the highest percentage of extreme poverty in México. It is the only one of the 19 municipalities of La Montaña that doesn’t have a paved road connecting its municipal center to the region.

In the rainy season, a 4×4 vehicle is needed to cross the last 20km to reach the municipal center, because the highway was never built.

Before we arrived to Tlacoapa, we passed by dozens of houses built by the Secretary of Agricultural, Territorial and Urban Development (SEDATU, created by the Peña Nieto administration and led by Carlos Ramírez, Jesus Murillo Karam and Rosario Robles herself), as part of the plan to rebuild La Montaña.

But the houses, which look like tiny INFONAVIT (social housing) houses in the middle of La Montaña, are empty. The low quality of the construction and design (there’s no space for animals, and indoor bathrooms in an area with no sewage system) led residents to abandon them and remake their adobe houses on the sides of the hills.

Questions for the president

La Montaña has been harshly impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic. The lack of access to health services has impeded treatment of sick people. In fact, Covid-19 hasn’t been the main concern in this area, where food security is a central issue.

Tlacoapa is only 400km from Mexico City, but it takes more than 9 hours to arrive by car. In the municipal center there is no cellphone network, limited internet and unstable electricity.

Incredibly, this municipality was one of the first places in the world to receive the vaccine for Covid-19, because the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador prioritized vaccination in the most remote regions of the country.

When we arrived, locals told us it was urgent that the hospital that was promised by the Peña Nieto administration open. The new hospital was built and equipped, but for an unknown reason, it was never opened.

On March 17th, we brought the issue of the hospital to the presidential press conference. “The INSABI [Secretariat of Health for Wellbeing] will go on our behalf to La Montaña, to see about that hospital,” responded the President.

A few weeks later, on April 6th, the director of the INSABI, Juan Antonio Ferrer, arrived in Tlacoapa together with Guerrero’s health secretary, Carlos De la Peña Pintos, to see the hospital and plan the inauguration.

On May 27th, we returned to the presidential press conference to ask. That time, Ferrer himself responded that the hospital would be ready in two weeks.

“We saw that the hospital is in good shape. It’s been under construction for eight years and what was badly planned, according to experts, was that there were only three beds. But in 10 days, two weeks maximum, the hospital will be running… As will others that the President instructed us to build, which are also in the La Montaña region in Guerrero, we will announce when they will be opened to begin to serve the people.”

On June 13th, INSABI announced in a communiqué that the Tlacoapa hospital would begin operations that week.

In reality, the hospital beds weren’t the main problem.

After the announcement that the hospital would open, Pie de Página traveled to Tlacoapa a second time.

What we found was a paradox: the people have a hospital that is much better than others in the region, outfitted with modern equipment that they can’t use because there are no specialists, and no supplies.

Ambulances without gasoline, operating rooms without surgeons

In front of the hospital there is a Mercedes Benz ambulance, which is not being used because the hospital doesn’t have gasoline to transport patients. In any case, according to hospital director José Ángel Antonio Núñez, the vehicle is used to bring patients to other regions where they can receive care. If, he clarified, the family is able to pay for the gasoline.

The closest cities to take patients to are Tlapa, which is three hours away, or Chilapa, which is six hours away. But in the case of a broken bone, they have to go to Chilpancingo, the capital of Guerrero, which is 8-9 hours away. And the families have to pay their own costs to stay in the capital.

“I used to take patients with broken bones to Malinaltepec, but they don’t want to take them anymore, they don’t have enough staff,” said nurse Maru Estela Espinoza Aguilar.

The recently opened hospital is large and dark. The modern look of the building contrasts with the dirt roads and the small houses in the area.

It looks like nothing was spared in the construction of the hospital, but also, it appears those who designed it don’t understand a thing about hospital architecture: the building has video cameras that are not connected; smoke alarms that don’t work; an elevator that no one needs because it goes to the second floor but all patient services are on the first floor; and a generator, which doesn’t work because there is no money to buy diesel. Almost every day the light goes out in the afternoon, according to the director. Some of the lights already need to be repaired.

It’s obvious that the hospital is operating below its capacity. Even though there is an operating room with tools and modern equipment like an X-ray machine, ultrasounds, sterilizing equipment, a delivery room, anesthesiology, cauterizing machine, and beds, almost nothing can be used.

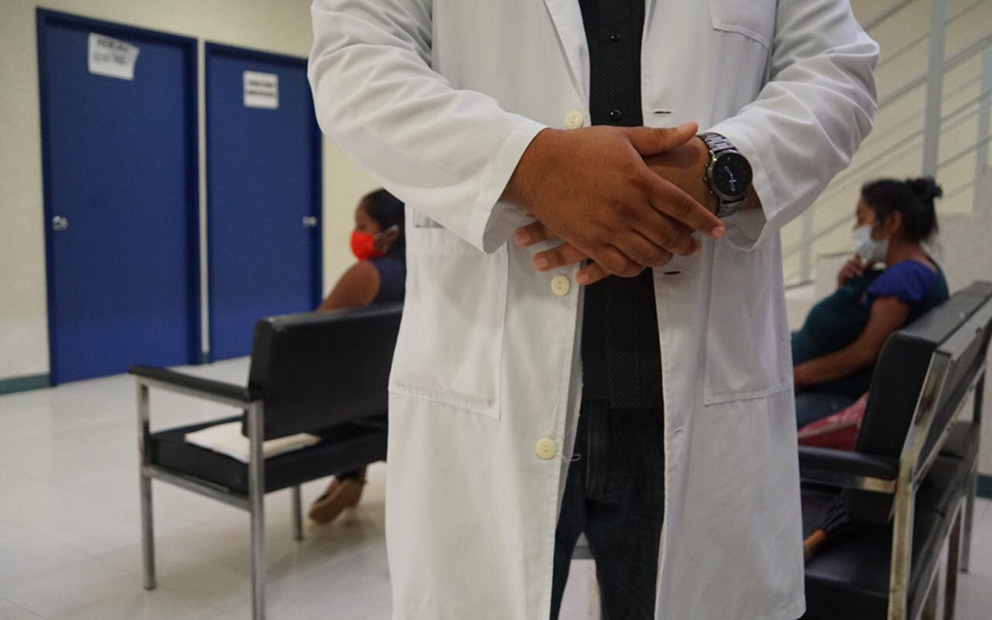

“There’s no specialist doctors,” said the director, who said that “we always have to work overtime, we come in at 7am and we don’t know when we can go home.”

Núñez is used to resolving problems and improvising. After all, a few weeks ago people from the town were still being seen at the Communal Goods House, while this hospital was used as a warehouse for the million dollar equipment that was bought with the reconstruction fund.

In a tour of the new hospital, the director told us “we haven’t had any patients, because, well, the people know we don’t have everything and they leave. If they come it’s just for a check up.” Even those that do arrive for appointments have to buy their own medicine.

“What medicine are you lacking?”

“If I made you a list it would be enormous, we don’t have syringes, yellow, black or green needles, we don’t have so many medicines, we don’t have Dexamethasone. We don’t have medicine in the red box, the red box is for emergencies. If a patient comes in in a bad state and we need medicine from the red box, we don’t have it. We try to stabilize them with what we have and we send them on to Tlapa.”

Between the white walls of the new hospital a small, well used stove is still being used to sterilize medical equipment, even though there is sterilizing equipment. Why? “We don’t have the key to where the other equipment is, and no one here knows how to use it.”

The rains over the last weeks have created small floods in the hospital, a stream of water flows through the emergency room, and the roof is also leaking.

“Has any of the medical equipment been ruined by the flooding,” we asked.

“I don’t know, we haven’t used it.”

“What’s the problem here, why don’t the resources arrive?”

“I could say it’s a problem of jurisdiction, but it isn’t that. Most of it is on the state level, but they tell us it’s federal. So we don’t even know where to go, they send us back and forth, from one to the other.”

“How much does a hospital like this cost?”

“I don’t know, but what we see in the documents is that it cost at least [3.5 million dollars]. That’s for the construction and the equipment.”

What Nuñez says can be checked against the Health Secretariat’s website: $2.5 million were spent by the National Fund for Natural Disasters, another million from the Budget Care Fund.

No interest from doctors, nurses

From June 8 to 11, INSABI published a call to contract 46 people in the Tlacoapa hospital, including administrative personnel, maintenance and janitorial staff, security guards, human resources, translators, specialists in gynecology, surgery, anesthesiology, odontology, a driver, a warehouse specialist, a psychologist, social workers, a pharmacist, an x-ray technician, people to wash linens, nurses and general doctors.

“The Institute of Health for Wellbeing (INSABI) emits the following call directed to health personnel interested in participating in the selection process in order to staff the Medical Unit of a marginalized or remote community described below, reads announcement No. MDB-001/GRO/H.C. TLACOAPA/2021.

The revision process for those seeking jobs was to be from June 12 to 14, and on the 15th the results were to have been announced. The contract would have started on June 16 for six months. But nobody applied.

“Los médicos no quieren ir para acá porque no hay condiciones para trabajar”, resumió la enfermera “The doctors don’t want to come because there aren’t conditions for them to work,” said nurse Espinoza, who is the health authority in the municipality.

It’s a structural problem, say those already working in the hospital. Of the 34 employees, only two would be permanent. The rest would have to renew their contracts every six months. The six doctors juggle to cover the morning, weekend and night shifts, for a monthly salary of US$350.

Old hospital, old problems

The newly opened hospital isn’t the first to be built in Tlacoapa.

The old hospital, which had to be evacuated due to risks caused by the passage of Ingrid and Manuel, wasn’t even that old. It was inaugurated in 2001 by then governor of Guerrero René Juarez Cisneros. It operated under the umbrella of the Popular Insurance program during the government of Vicente Fox.

The old hospital doesn’t appear to be all that damaged. It is used as a warehouse, oxygen tanks and hospital equipment that weren’t used before the equipment was purchased for the new hospital can be seen through the windows.

Beside the door that is closed with a padlock is a plaque which was installed on the day of the inauguration. The plaque indicates that the hospital was built thanks to the Municipal budget line 33, and it has the name Basic Community Hospital “Toni Starr de Camil.” It was named after the New York model who married various businessmen with interests in Guerrero. Her last husband was Jaime Camil Garza, a businessman active in political consulting and entertainment.

In sum, in one of the places with the highest levels of marginalization in Mexico, two hospitals have been built in 20 years: one in a risky area, and another that is essentially a warehouse for a multimillion dollar investment. For locals, access to health services remains a distant promise.

In front of the old hospital, we met with Juana Orijuelo, who is Indigenous Me’phaa from a nearby community, who tells us she “had a daughter who wants to study,” but that she can’t pay for school because she can’t work and she doesn’t have any money.

The woman, who is forty but whose teeth are worn and whose face is wrinkly, said that she hasn’t gone to the new hospital, even though she has been feeling ill for a year. “They say I don’t have anything wrong with me, that it’s just gastritis, but I can’t work anymore.”

José Ignacio de Alba was educated in Catholic schools until he became an atheist. He is a shy wanderer, and never finished his journalism degree. He tends to have more faith in the old narratives than the new, and he likes to write stories.

Isabel Briceño has never liked the fact that happy stories come to an end, which is why she captures them on camera, she captures sad stories in a search for answers.

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona