Indigenous organizations joined together to create a common front against megaprojects after López Obrador announced their development is in the “national interest.” The groups that gathered will realize a Caravan for Life beginning March 22, 2022.

Text and photos by Ángel Melgoza, originally published January 16, 2022.

Translated by Dawn Marie Paley for Pie de Página in English.

SANTA MARÍA ZACATEPEC, PUEBLA– “The gas doesn’t flow here,” said Campeche, referring to the Morelos Gas Pipeline which we walked along on the morning of Sunday, January 16th. Campeche is a 36 year old man who is part of the United Communities of the Cholulteca Region in Puebla. This is the same group that has had a blockade outside of the Bonafont water bottling plant, which they blame for massive overuse of underground water.

The people of Santa María Zacatepec, where the Bonafont plant is located, watched as the land sank, forming a massive sinkhole 150 meters in diameter on May 29th of last year, just two months after they started their protest for water.The sinkhole became known nationally as “el socavón,” the distance between the part of the Morelos Gas Pipeline we walked along and the sinkhole is around 400 meters. The people of Zacatepec imagine the magnitude of disaster that an explosion provoked by an earthquake, a new sinkhole, or by fuel theft could cause. On October 31, in the city of Puebla, around 30 minutes from this town, a clandestine siphon off the gas line exploded, killing five, injuring 17, seriously damaging 50 homes, and forcing 2,000 people to evacuate.

Standing in front of the sinkhole, Miguel López Vega said it is a clear demonstration of the destruction and death provoked by industry.

“In this region, Bonafont extracts 19 liters [of water] every second; the thermoelectric plant would use 500 liters of second; Volkswagen uses more than 1,000 liters per second; Hysla also uses 400 liters per second.” All of this extraction is believed to be at the root of the sinkage.

“Zedillo, Fox, Calderón, Peña Nieto and now López Obrador,” says Campeche, listing the presidents residents of this region have faced off against in order to avoid the installation and operation of the gas pipeline. During Zedillo’s time, in 1998, the project was called the Transportadora de Gas Zapata. Back then, the villages of San Lucas Nextetelco, Cuanalá and San Juan Tlautla organized to prevent the project from crossing their lands.

They were able to hold off the project during the first two presidents, but Félipe Calerón made an alliance with Rafael Moreno Valle, then governor of Puebla, which the villagers were unable to stop. The pipeline was under the custody of the Mexican Army and the Federal Police. Since then, what the state hasn’t managed to do, according to Campeche, is to get the gas flowing through the pipeline.

The Morelos Gas Pipeline is part of the Morelos Integral Project (PIM), which Calderón inaugurated in 2007. The PIM is an infrastructure project designed to generate electric energy through thermoelectric plans, a gas pipeline, an aqueduct, and a network of energy transmission via high tension towers.

“This project has been stopped many times, precisely because of the refusal of local people to accept it. And that’s why López Obrador made that decree,” said Campeche, referring to the Presidential Accord. For him and many others from impacted Indigenous communities, the Accord “makes us worse than terrorists, we are now enemies of the nation, for defending our land,” said Campeche.

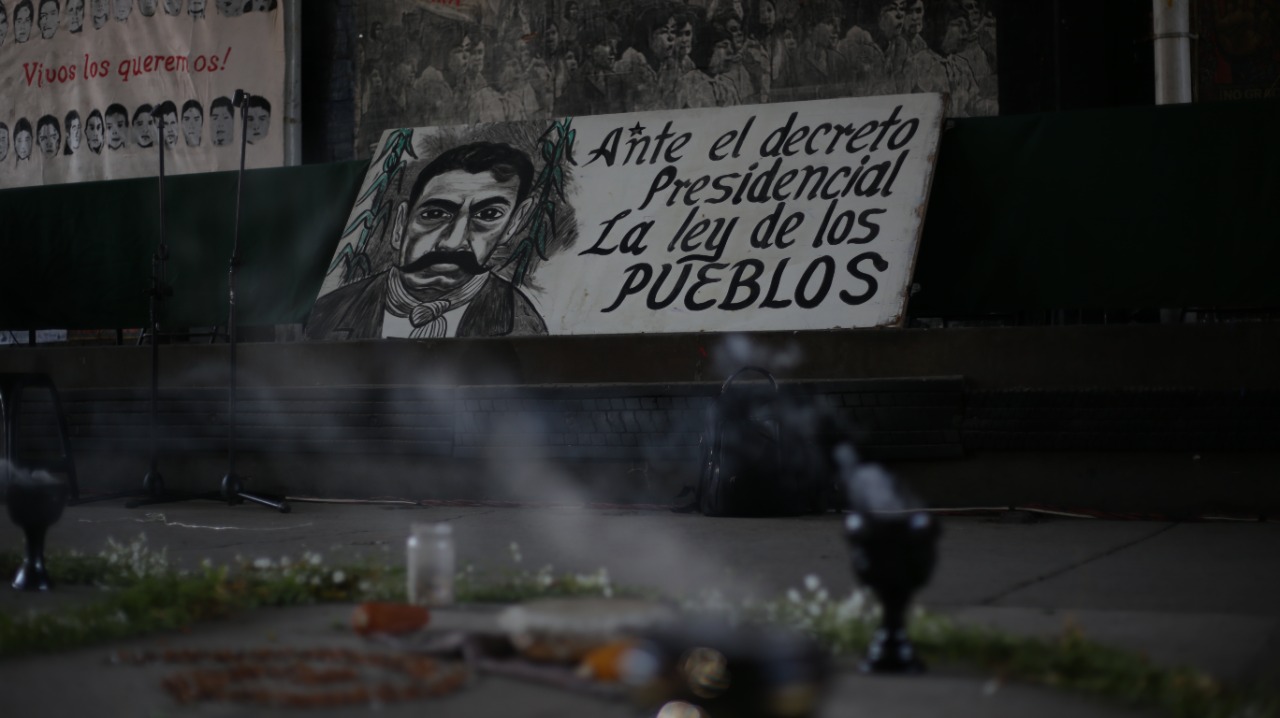

Land defenders here said they have been called anti-progressives, backwards, and ignorant. The stage here is decorated with banners and posters: demanding the return of the 43 disappeared students from Ayotzinapa; demanding that Bonafont leave; announcing struggles against pipelines; showing the photo of Emiliano Zapata and the flags of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN). Groups from the north of Puebla and Hidalgo, from Sonora, Jalisco and Morelos took to the stage to share their stories and their demands.

An accord to impose megaprojects

The National Gathering Against Gas Pipelines and Projects of Death wrapped up on Sunday, January 16. It took place in Altepelmecalli, the House of the People, a structure belonging to the Bonafont bottling plant –owned by the transnational Danone– which has been occupied since last year.

The gathering was convened by 13 organizations, including United Communities of the Cholulteca Region, the Peoples’ Front in Defense of Water and Land Morelos-Puebla-Tlaxcala (FPDTA), and the National Indigenous Congress (CNI). The national gathering represents an important opposition against the Presidential Accord that President López Obrador emitted on November 22nd.

AMLO’s accord prioritizes large infrastructure projects that, because of their “complexity and size, will be considered priorities or strategic for national development.” In addition, it instructs federal agencies to provisionally authorize these projects “in a maximum of five business days” so as to obtain the rulings, permissions, or licenses required to start said projects.

The three main points of the accord have been called unconstitutional and illegal by specialists; the actions stemming from this accord could have serious consequences, including the violation of human rights.

The organizations that convened the gathering said the current federal government is “the government of megaprojects, of militarization, of an attack on communities,” and emphasized that the Maya Train, the Trans Isthmus Corridor, and the Morelos Integral Project are three of the main threats against original peoples.”

The Caravan

The final result of the gathering was the announcement that a Caravan for Life will depart from Altepelmecalli, the House of the People, on March 22, 2022. The caravan will travel through towns, communities and territories resisting megaprojects, and will end a month later, on April 22, in the city of Juchitán, Oaxaca, in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

Saturday was spent going over cases, with participants taking part in meetings, and with a show of regional dances. On Sunday, we traveled along a part of the Morelos Gas Pipeline, to the sinkhole, and then attended the final assembly. The message that came out of Puebla is that of the autonomy of Indigenous peoples; of resistance to megaprojects that go against their way of life; that of self-determination and community law. In the words of Miguel López, “the life of our people comes before industry.”

“Imagine where we have our fields today, what will they be tomorrow? An industrial zone contaminating the Metlapanapa River, drying up our wells, forcing us to work as laborers, contaminating the water, the air, we’d rather keep our fields for our community to plant and harvest healthy food,” said Campeche.

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona