Rarámuri people protest land theft in Chihuahua

12 junio, 2021

Although there are records of the Rarámuri’s existence in the Barrancas del Cobre region dating back to 1915 as well as attempts to be recognized as the territory since 1980, agricultural authorities have ruled in favor of PRI-affiliated businessmen such as Omar Bazán Flores, former leader of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and state legislator who ran for re-election, and Ricardo Orviz Blake, a former PRI legislator and owner of a residential housing development in the city of Delicias

Text and photos by Óscar Rosales, originally published by Raichali Noticias on May 31, 2021.

Translation by Elysse DaVega.

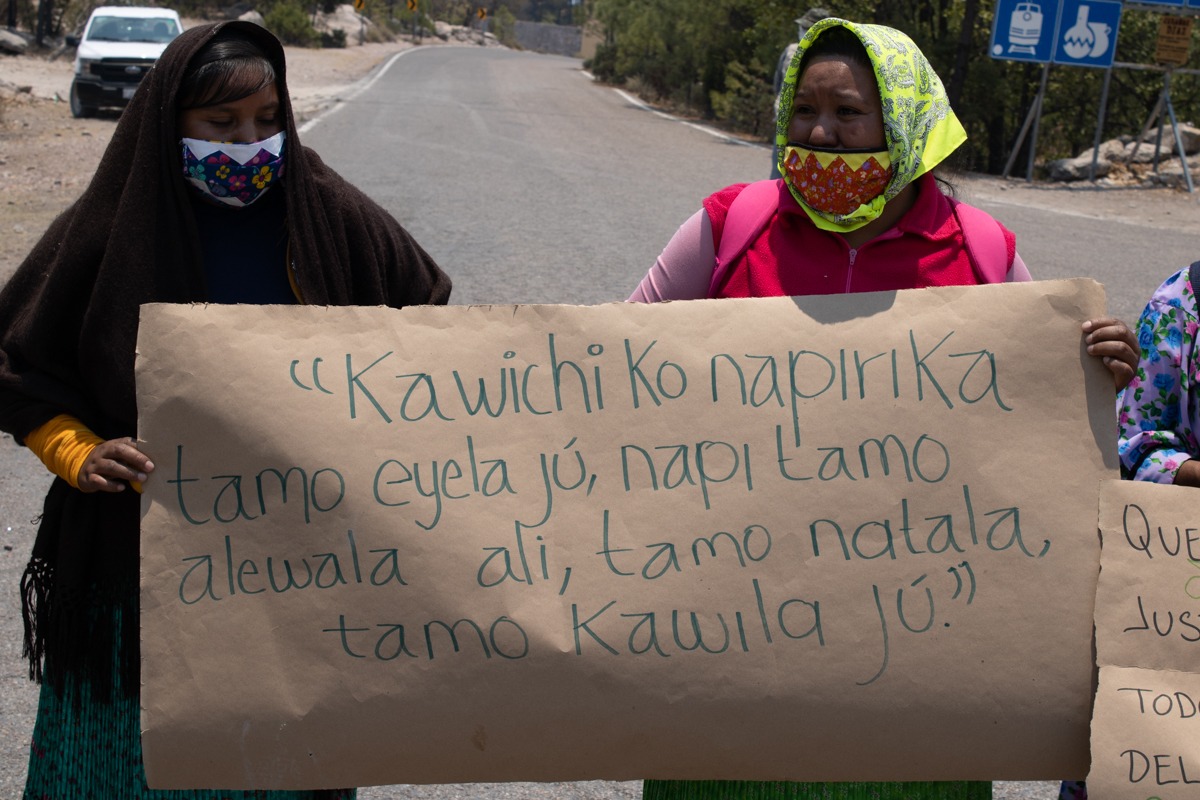

CHIHUAHUA–Dozens of Rarámuri from the Mogótavo community in Urique, a municipality in northern Mexico, held a peaceful blockade on the morning of Saturday, May 30th on the Creel-San Rafael highway near the Barrancas del Cobre limit to demand a stop to the lawsuit against its residents brought by businessmen linked to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

As the Sierra Tarahumara Indigenous community fights for the recognition and protection of its territory; figures linked to the PRI file a penal lawsuit against the three governors of the Indigenous community for «aggravated dispossession,» through which they intend to evict more than 80 Rarámuri families.

Although there are baptismal records of Rarámuri people in Barrancas del Cobre dating back to 1915 and attempts to regulate the territory since 1980, the Superior Agricultural Court has always ruled in favor of mestizos, or mixed-race Mexicans, and denied the existence of the community.

Among the plaintiffs are Omar Bazán Flores, former head of the PRI of the state of Chihuahua and current local representative seeking reelection, and Ricardo Orviz Blake, another former PRI leader and owner of a housing development named after him in the city of Delicias.

Also involved in the case against the Rarámuris are Jesús Alberto Cano Vélez, former PRI representative in Sonora; Agustín López Dumas a Delicias businessman; and Ricardo Valles Alvelais, the brother of Chihuahua’s former secretary of tourism. Alvelais died in 2015, but his family has continued to use his name in the legal process.

Ódame and Rarámuri communities including Huitosachi, Cordón de las Cruces, Bosques de San Elías Repechique, Bacajipare, Malanoche and Bawinokachi joined the Saturday demonstration. With banners and signs, they demanded recognition of their people and respect of their ancestral lands.

Accompanied by the chords of a guitar-violin duo, the Indigenous groups danced for the freedom of Mogótavo residents to sow, honor and tend the land that they consider sacred.

Civil associations Awé Tibúame, the Community Technical Consulting Firm (CONTEC), the Center for Training and Defense of Indigenous and Human Rights (CECADDHI), the Sierra Madre Alliance (ASMAC) and the Commission for Solidarity and Defense of Human Rights (COSYDDHAC) also supported the protest.

A long struggle

State police forces arrived during the protest to question participants in the highway blockade, who distributed flyers to tourists passing by. Despite the interrogation of the Indigenous leaders, the group carried on peacefully.

Raíchali had the opportunity to interview one of the longest-standing residents of Mogótavo. She shared her memories of the beginnings of the land seizure by mestizos in her territory and the fight that they’ve carried out. Her granddaughter served as her translator.

«She grew up here in Mogótavo. The issue began when she was little; she remembers very well that she used to walk by where the hotel is now. There wasn’t a hotel back then, just houses. Her grandma and grandpa would go too, they had houses close to here,» her granddaughter explained after hearing her grandmother’s account in her native tongue.

«And then Efraín Sandoval suddenly wanted to demolish houses, he got very angry. He didn’t want them to build more houses. They would bring lumber and Mr. Sandoval would get mad because he didn’t want them to chop down the pine trees,» she said.

Odile Sandoval, owner of the Barrancas del Cobre tourist complex and daughter of Efraín Sandoval, would be the one to eventually sell 154 hectares of Indigenous land, worth more than US$2 million, to PRI-affiliated businessmen in 2008.

The building known as «Barranca’s Plateau» (now named «Five Brothers», signifying the number of children Efraín had), was granted to the Sandoval family by the Secretary of Agricultural Reform in 1999, during Ernesto Zedillo’s presidential term.

«We’ve been traveling back and forth to Mexico City for a long time and never found a solution, so we tried in Chihuahua and they didn’t pay us any mind there, either,» the granddaughter translated.

«Her grandparents lived there, her ancestors. It’s not right what they’re doing. They don’t live here, we do, and we always have.»

Miguel Manuel Parra, a spokesperson from Mogótavo, thanked the Rarámuri and Ódame communities, whose pleas converge into one cause, for their support.

«There are people that want to take away the birthplace of Rarámuri families. We fight so that they respect our right to the territory, to our land, where we were born.»

Parra questioned Mexico’s role in equipping politicians and businessmen with legal tools that facilitate the suppression of Indigenous communities. For them, the dispossession lawsuit is an absurdity meant to perpetuate criminalization and attack against Indigenous communities.

«Rarámuri territory used to be much larger. Don’t settle for them running us out of those more productive areas, they want to take it all,» he pointed out.

The accusatory hearing against Mogótavo’s Indigenous leaders took place in the city of Cuauhtémoc, Chihuahua, on June 9.

A collection of voices

Members of other Indigenous communities participating in the protest discussed the problems they face in their villages, where land seizure, illegal deforestation and lack of recognition and consultation are common.

Residents of Cordón de la Cruz reported that the Secretary of Territorial and Urban Development (SEDATU) continues to ignore their reports of livestock theft by mestizos, the first of which dates back to 2016.

According to testimonies, the federal body promised to resolve the problem within six months. It’s now been five years. Some families have felt obliged to move out of the community due to threats by mestizos, who set up fences and claimed the land and livestock as their own.

«In October 2019, we went to Mexico City to demand a ruling, but to this day they haven’t resolved anything,» they affirmed.

To the same effect, the Bawinokachi demanded the federal government’s recognition of their community, which was originally requested by residents in 2014.

«They’ve said to us that they continue to make progress on it, but they haven’t provided anything in writing as to whether they’ll support us or not,» their spokeswoman explained.

Another community that shared their experiences was Bosques de San Elías Repechique, who discussed the land seizures they suffer. The Rarámuri group said that the Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) continues to distribute permits to people outside of the community without taking Indigenous residents into consideration.

They claim that the megaprojects in their territory have been carried out without consultation. Projects such as the airport in Creel and the San Juanito gas pipeline and aqueduct were constructed without taking Indigenous views into account.

All of this continues, even after a ruling from the Eighth District Court that recognizes the community. Community members said the government of Chihuahua disregards the ruling entirely.

«We see the government implementing tourist projects, and we’re the ones that are affected, because land has been sold to people outside of the community without taking members of the Rarámuri community into account,» said a spokesperson from Bosques San Elías Repechique.

An example of this disregard came to a head in June 2020 when the construction of a Rarámuri sewing shop was halted by members of the State District Attorney’s office (FGE) in Cerros de la Virgen.

Land defenders under constant threat

Business owner Fernando Cuesta filed a lawsuit in which he claimed, similar to the situation of Mogótavo, intimidation against him. Despite the FGE’s presence in the area, theft and threats have become a normal part of life for those who defend their land.

«What I’ve personally had to experience, well, they’ve attacked me with guns, they’ve threatened me. At that time, I had no one to turn to,» the Rarámuri spokesman said. «We’ve been violated by the Mexican state as a community, as a people; our land, our way of life.»

This report was originally published by RAÍCHALI, which is part of the Media Alliance organized by Periodistas de a Pie. You can read the original here.

Click here to join Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona