Lithium, violence and special interests in Sonora

15 abril, 2022

In Sonora, the use of paramilitary groups to weaken opposition to mining is an ongoing practice. Local and national corporate and political interests have created a reality with a single horizon: accumulation and profit, at the expense of life.

Text by Alejandro Ruiz, originally published April 6, 2022.

Photos by Nacho Ruiz and Galo Cañas / Cuartoscuro and courtesy.

MÉXICO CITY—The debate about the nationalization of lithium has again put Sonora in the spotlight, as the reserves of this mineral are in the municipality of Bacadehuachi and the region known as “lithium valley,” located in the northeast of Sonora, in the western Sierra Madre mountains.

The proposal, jump started by the President’s party, has been met with resistance from the political opposition in congress, as well as from the extractive industries which, over the last decades, has overseen mining concessions in the northern state.

Their arguments, articulated by the Mining Chamber of Mexico and BNamericas Group and taken on by politicians, businessmen and public figures, center on the supposed non-existence of lithium in the region. They also point to a lack of government infrastructure and technical knowledge to mine and transform the resources.

But the reality is otherwise. That’s what Rompeviento TV’s reportage, titled Mexico: Lithium Exposed, showed. Not only does Mexico have lithium, it has the technical resources needed to exploit it.

Days after its publication, the filmmakers received death threats.

Behind the opposition to the nationalization of lithium there’s a cluster of businesses that, in some cases, have established themselves in Sonora through violence and the displacement of campesinos and communal landowners (ejidatarios).

Politicians, businessmen and crime groups have been operating mining and agribusiness in Sonora for decades, leaving in their wake extreme violence: massacres, killings, displacements and disappearances, according to activists from the region. Even so, there’s little discussion about what’s happening there.

Mining in Sonora

Jano Valenzuela is a sociologist and activist who is part of the Yaqui nation. He has participated in organizing in his community and studies how violence works in his territory and in the state of Sonora.

For him, trying to understand Sonora without looking at the role of the extractive industries is pointless.

“The main dynamic that has been imposed in Sonora is the expansion of the extractive industries. Especially the mining industry, but also industrial agriculture… The mining industry is expanding in Sonora, so for example, almost all the territory is concessioned to foreign mining companies. Even though the president has said there will be no new mining concessions, the territory is already concessioned,” he said.

According to a document called Mining Panorama of the State of Sonora, published by the Secretary of the Economy in 2020, there are 21 mines in operation in the state. Of them, 14 extract metals and 7 non-metallic minerals.

The most exploited minerals are copper, gold, silver, graphite and coal. In addition, there are lime, iron and molybdenum mines. All of these minerals are used to make electronics because of their properties when alloyed with other minerals.

In these territories, concentrated in the mountain and desert regions of Sonora, but also in the central and southern regions of the state, where the Yaqui live, social conflicts have escalated over the past years. This is especially true since the war on drugs started by ex-president Felipe Calderón Hinojosa. During his term, 13,000 concessions for mining in Mexico were granted.

Territories of violence

Jano Valenzuela says “all the violence that’s taking place in Sonora is intimately linked to the expansion of big capital. Capital from the extractive industry, but also from drug trafficking, human trafficking and legal industries like maquilas and large scale agriculture.

For Valenzuela, the key businesses of organized crime are joined with the interests of extractive companies. This happened through the use of paramilitary structures that are connected to criminal groups to eliminate the opposition that exists in territories where minerals are located.

“Of course there is a direct relationship between the exercise of violence in the hands of the state and paramilitary groups. Organized crime doesn’t just look after its economic interests (drug trafficking and migrants), it also exercises violence on behalf of mining interests,” said the Sonoran sociologist.

By way of example, says Valenzuela, is the case of the El Bajío Ejido, in the municipality of Caborca. Dozens of ejidatarios (communal land owners) have been killed and disappeared by paramilitaries who, he says, work for Penmont mining company, property of the Bailleres family. He also denounced the interests of the ex-governor of Sonora, Claudia Pavlovich.

Jano also points to aggressions against the Yaqui people on their lands, which were legally granted to them by presidential decree since the middle of the 20 Century.

“In Yaqui land alone there are 25 mining concessions… We’ve been seeing a tendency, over the last 30 years, of the concentration of homicides in the five municipalities that make up Yaqui territory. In 2021, these five municipalities accounted for 54.6 percent of homicides in the state,” said Valenzuela.

Today, there is a conflict in this region stemming from the Independence Aqueduct, a water diversion system, that in recent months has been a source of controversy due to the Yaqui Justice Plan the federal government has implemented in the area. The dispute is due to the fact that some among the Yaqui, who say they are the legitimate traditional guard of Loma de Bacum, have stated that the federal government has usurped their authority.

For Valenzuela, the struggle that the Yaqui have been carrying out against the Sonora Gas Pipeline since 2012 reflects the ongoing conflict between the government and extractivism in the region.

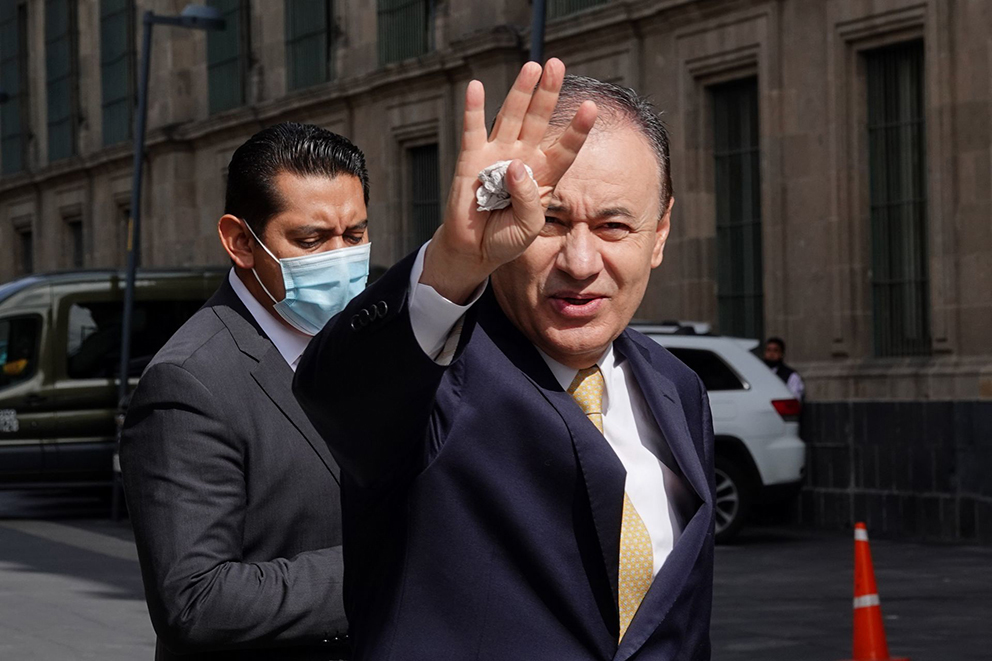

One impact of this, he says, is related to the business dealings of the ex-secretary of Federal Citizen Security and Protection (SSPC) who is now the governor of Sonora, Alfonso Durazo. He is a shareholder in the company Agua Prieta Gas, which was founded by his brother Héctor Manuel.

Politicians and businessmen, or political businessmen

In his yearly declaration of properties and conflict of interests for 2020, Durazo reported an income over $7,000,000 (approximately US$350,000). Of that, $4,719,963 (approximately US$235,450) are from his participation in the gas company.

Jano Valenzuela thinks the governor’s business in Agua Prieta is a clear conflict of interest that exemplifies the problem of politics and violence in the state. Durazo’s gas company is located where the Sonora Gas Pipeline is supposed to end. The Sonora Pipeline was marketed as a project that would allow the sale of gas to the US.

Similarly, says the sociologist, Durazo has major investments in the housing sector in Hermosillo. In other words, the politician is close to long-time business groups in Sonora.

“Alfonso Durazo sells himself as a common man. But the Durazo Montaño family is part of a colonial and aristocratic elite in Sonora that have always held power in the mountainous region in the state’s north east. They’ve been in power for centuries,” said Valenzuela.

For her part, ex-governor Claudia Pavlovich, who is linked to businessmen like Lemenmeyer, Mazón, Camou and Castelo, comes from a family with roots in industrial agriculture. This is another one of the key economic sectors in Sonora, which is just as strong as mining.

In fact, the family history of the ex-governor goes back to the beginning of the 20th Century, when her Yugoslav ancestors, D. Lucas and D. Felipe Pavlovich, became important orange producers in the state of Sonora.

The key sectors that contribute to Sonora’s GDP are mining, housing and services (sectors to which the Pavlovich and Durazo families have been connected), and the role of the agricultural industry is also fundamental.

Sonora’s northeast

Sonora is among the states with the highest production of certain greens and citrus fruit nationally, this production is concentrated in large part in the northeast and in the south of the state.

Regardless of this, the mountainous northeast, which borders Chihuahua, is where Lithium Valley is located. It also has a central place in industrial agriculture, particularly in crops for animal feed. According to information published during Pavlovich’s term as governor, this area has received millions of pesos in investment for housing projects, highway modernization and increased services.

Jano Valenzuela understands lithium valley such:

What we know is that [lithium valley] is a territory that is totally concessioned, where there doesn’t appear to be a criminal process to destroy the social fabric. What we have seen over the past months is a very active presence of Alfonso Durazo (Alfonso Durazo Chávez), who has been very active traveling through the region and promoting energy reform.”

It wouldn’t be the first time that Durazo Chávez has participated in campaign activities that, by law, his father is forbidden from doing. Over the past weeks he had been campaigning for the Presidential Recall vote in San Luis Rio Colorado. His presence in the mountain region, which according to Valenzuela has been an electoral bastion for the Durazo family, isn’t a coincidence.

The Duraznos (father and son) have both been involved in media scandals in which they are linked to organized crime, principally the “Sinaloa Cartel.”

While he was President Vincente Fox’s personal secretary (2000-2006). Durazo Sr. was accused of having ties with Nahum Acosta Lugo, a National Action Party politician who, in 2013, was accused of leaking information from the president’s office to the Sinaloa Cartel. The accusation faded away. Durazo was never investigated, though he was accused of helping Lugo gain access to the President’s office.

Decades later, while Durazo Sr. was head of the SSPC in the current federal government, a video was leaked hinting that Durazo Jr. had gone to school with Ovidio Guzmán, the son of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, head of the Sinaloa Cartel. Guzmán Jr. has also been identified as a drug trafficker. The video was circulated days after a failed operation in which the Mexican marines attempted to capture El Chapo’s son.

The video was disqualified by López Obrador during a morning press conference, and the scandal appears to have been forgotten.

The relationships of the Durazos and their presence in Sonora’s northeast seem to be intact.

There have been many complaints about the presence and control of criminal groups in the region. During Pavlovich’s term and to the present, violence in Sonora along the border with Chihuahua has been constant. Probably the most emblematic case is the paramilitary attack which resulted in the massacre of the LeBaron family in 2019.

The massacre of the LeBarons

The phone rings. On the line is Alex LeBaron González, who is part of the LeBaron community in the municipality of Galeana, Chihuahua, a few kilometers from the border with Sonora.

On November 4, 2019, nine members of his family was horrifically murdered while driving to Galeana from Bavispe, Sonora. Three women and six minors were killed.

Then head of the SSPC, Alfonso Durazo, detailed the chronology of the crime, which was attributed to a confusion between organized crime groups in the region.

Bavispe is located on the lower slopes of the Western Sierra Madre mountains, an hour and a half from Bacadehuachi and lithium valley.

Prior to the massacre, in 2018, Alex LeBaron was a federal congressperson for the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) for District Seven, representing Ocampo Chihuahua, another a mining district.

LeBaron says that while he was a congressperson, the mining laws (which were derived from Enrique Peña Nieto’s energy reform) began to favor the communities where the companies were based.

“The municipalities began to receive direct social programs and the investments were notable right away,” he said.

Some of the advances are connected to the fact that the capital of the mining companies setting up in Sonora and Chihuahua are foreign, and particularly, he said, from the US, Canada and Europe.

He also said that organized crime has played a crucial role in creating problems in the territory.

“We know that organized crime has played or plays a key role. Not just in these regions, but in the public policies that are adopted in these municipalities are impacted by drug trafficking. Unfortunately in Chihuahua and Sonora, especially in the mountain regions, this is even more evident,” he said.

One example of this, says LeBaron, is the killing of nine members of his community, which is Mormon. For him, the dispute in these lands cannot be understood as a conflict between cartels. It goes beyond that.

“I don’t have any doubt that there are hidden interests seeking to firm up their power in different parts of the mountains between Chihuahua and Sonora. I think that without a doubt a lot of what we’ve seen in the past few years has to do with that,” he said.

One way to explain what is going on in this territory, Alex LeBaron explains, using his analysis of what happened in his community, is the influence of interests that foreigners, and North Americans in particular, hold in the region.

“When the massacre happened in our community, we saw signs of groups who were influenced by groups in the US,” he said.

LeBaron makes clear he doesn’t have concrete proof, but as he has followed up on the tragedy, he has found information that leads him to believe there was the participation of such groups.

In particular, this is related to the context of the 2018 federal elections, during which, in his way of seeing things, the alliances between organized crime and powerful political groups were modified. This transformed the power relations in the territory, confronting the interests of various criminal groups, among them some which act on behalf of US groups, he says.

“I don’t say this lightly. What’s cleat to me is that what happened to my family in La Mora, in Bavispe, with the election of Durazo as governor of Sonora and the actions and confrontations of criminal groups in Sonora, there are a lot of connections that can’t be coincidental,” he said.

The US connection

On March 31 of last year, John Kerry traveled to Mexico for a meeting in the National Palace. His motive: to discuss the energy reform presented by President López Obrador.

Among Kerry’s key talking points, which have since been used by the White House, are that aspects of the energy reform could violate some of the agreements established as part of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, especially those related to the suspension of authorizations for electricity generation by private companies.

The position held by Kerry and the White House has been repeated by the Mining Chamber of Mexico, which also maintains that Mexico’s lithium reserves are insufficient to justify nationalized production.

As offensive as this is, it’s not new. The intervention of the US government in Mexico’s energy policies has deep roots, and exploded with the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1992.

Back then, US President Bill Clinton pushed the tri-national agreement, which led to the granting of over 25,000 mining concessions in Mexico. Just over 22 million hectares of Mexico’s national territory have since been exploited (or are being explored) by, for the most part, Canadian, US and European mining companies.

The Mining Law was modified due to NAFTA, and has undergone legal challenges after conflicts in rural villages and Indigenous communities across the country. The Mining Law, written during Carlos Salinas de Gortari’s presidency, is in conflict with various international treaties ratified by the Mexican government.

In addition, in 2006, Hillary Clinton, wife of the ex-president who was then the US Secretary of State, intervened through civil servants like ex-ambassador Carlos Pascual and the International Energy Commissioner, David Goldwyn, in the creation of energy reform carried out during Peña Nieto’s presidential term (2012-2018), according to reporting by DeSmog in 2015. US civil servants benefited economically from their investments in oil companies and by providing consulting services for the Mexican government.

The 2013 energy reform, in addition to removing Pemex’s monopoly on oil production, allows private companies to generate energy with Mexican resources. Another key promotor of this reform, who is linked to the Clinton family, is the former US ambassador in Mexico (2016-2018), Roberta Jacobson.

In addition to her diplomatic posting during the administrations of Barack Obama and Donald Trump, Jacobson helped coordinate issues along the US’s south border during a brief period of the Biden administration, which made her part of the North American National Security Council.

Jacobson, who maintains close relationships with the Clinton family, was also close to Madeleine Albright, the former US secretary of state during Bill Clinton’s presidency.

Albright was a key figure in the expansion of NATO in Europe before the fall of the Berlin Wall, when she was the US ambassador to the United Nations. She promoted the doctrine of homeland security while at the State Department as well as vis a vis a corporate group that became known as the Albright Stonebridge Group. Roberta Jacobson is also part of that group.

In 2021, Alfonso Durazo, as governor of Sonora, announced that Jacobson would become part of the state’s Sustainable Development Council. He made the announcement on social media, and said it would help incentivize investment in different strategic sectors in the state.

“I think that we can start to connect the dots and see a tendency, and again, I’m not saying this lightly,” said LeBaron. “These aren’t accusations either, but it’s really hard to grow up and to live on this side of the line between Sonora and Chihuahua without understanding that criminal groups are no more than those that execute the needs of certain interests, in Mexico, government interests, as whoever is in office isn’t disconnected from criminal groups. That’s the reality.”

“After what happened, and after seeing all the efforts by the President Andrés Manuel López Obrador to nationalize lithium, I think what’s clear for us is that there are interests that we don’t understand, related to the lack of lithium worldwide,” said LeBaron. “That’s not a coincidence.”

Communitarian nationalization?

Jano Valenzuela adds that, even when there are different interests at play, for him, legal and illegal economies connect through a modern logic that puts profit and capital above life, territory and community.

“The logic that is mobilized is that of the accumulation of capital. Every group, subgroup, and macrogroup has its own logic for the accumulation of capital: they ally themselves, they articulate themselves, and they split apart, depending on the needs of the market.”

That vision, he says, is what has dominated President López Obrador’s new energy reform.

“It’s worrying to see a dichotomous vision of reality, in the sense of market or state, in the electricity reform. We see the risk of nationalizing lithium and then having a Pemex-like company being the one that displaces communities in the country,” said the Sonoran sociologist.

That’s why he believes a true proposal for reform should go beyond the nationalization of resources, and attend to the problems of displacement and violence that are connected to extractivism.

“It should be a communitarian nationalization, so that it is the communities that organize, oversee and work the extraction of minerals, if the communities wish to do so,” he said. “They should have the support of the state for that.”

Jano says the proposal, in order to really benefit and support communities, should tend towards the creation of public and communitarian associations, not state-owned companies. Otherwise, “nationalization will fall short, because if it isn’t a communitarian nationalization, the ones at risk are the communities.”

If things don’t go this way, he said, “we could see abusive practices, displacement and the imposition and reproduction of modern logics, in the sense that a private company is only seeking to increase its profit share, when what should prevail is community logic.”

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona