Milpa Alpa is the borough in Mexico City with the largest number of households without access to running water, and the problem is particularly severe in San Salvador Cuautengo. Residents accuse local authorities of making money from private water supply trucks.

Text by Cuauhtémoc Osorno Córdova, originally published December 31, 2021.

Photos by Saúl López and Cuartoscuro.

Translated by Dawn Marie Paley for Pie de Página in English.

Mexico City–29,004 households in Mexico City don’t have a connection to the public system of running water. Most of the affected households are in the borough of Milpa Alta, specifically in the town of San Salvador Cuauhtenco.

In the city, 98.9 percent of households have piped, running water. In the boroughs of Benito Juárez, Coyoacán, Cuauhtémoc and Miguel Hidalgo the connection rate is nearly 100 percent, but in Milpa Alta, it is closer to 89 percent.

Milpa Alpa is the borough with the smallest population in the city (152,685 residents), it’s also the area with the most households without piped, running water (4,107 households). This is more than three times the amount than in Iztapalapa, the largest of the boroughs, where 1,278 households don’t have access to water). Milpa Alta makes up 14 percent of all the households without a connection to public water services in the capital city. In other words, around 16,000 people in Milpa Alpa –which has an average of four people per household– face severe complications in terms of accessing their human right to water.

Milpa Alta belongs to the so-called “C Zone,” which is a management district of the Water Systems of Mexico City (SACMEX). This area was concessioned to Tecnología y Servicios del Agua S.A de C.V. (TECSA), owned by the Mexican mining company Peñoles and the French transnational Suez. One of the TECSA’s responsibilities is installing new connections for drinking water and building pipes, as one of their contracts outlines that the company is obliged to “grant quality, on-time and friendly service to the public.” TECSA stopped operations in November 2021, when Claudia Sheinbaum’s government withdrew the contract because of austerity policies and in order to try and reign in the debts of large companies that consume water in the capital.

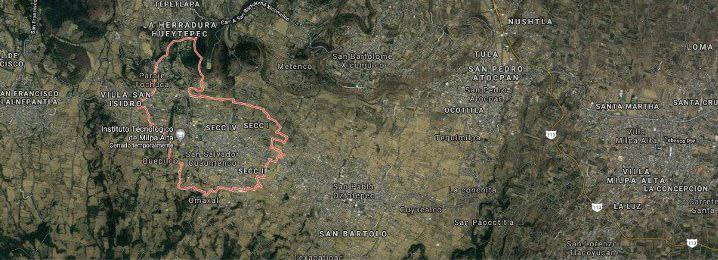

The town with the least drinking water in Mexico City

The town of San Salvador Cuauhtengo is located in the western part of Milpa Alta, bordering Xochimilco. It’s the location with the least amount of access to infrastructure in all of Mexico City; of 4,233 households, 645 don’t have water pipes. There is an average of 3.98 people per household there, which means nearly 2,500 residents are going without this service. They get their water primarily from water delivery trucks that operate in an unregulated way and take advantage of a fundamental human right.

Doña Rosalba vive desde hace tres décadas en San Salvador y es una de las personas que no cuenta con una conexión a la red de tuberías administradas por el Sacmex. Supuestamente su familia debería recibir cuatro tambos de agua de las pipas del gobierno de la capital cada ocho días, pero no es así.

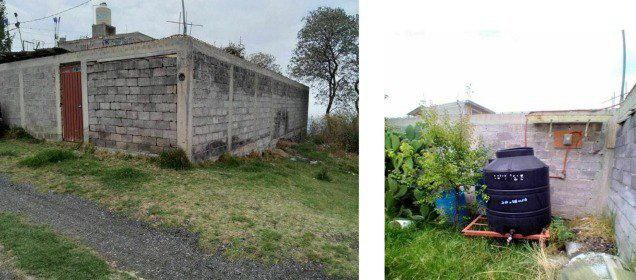

Doña Rosalba has lived in San Salvador for three decades. She is one of the people who doesn’t have a connection to the network of water pipes administered by SACMEX. In theory, her family ought to receive four barrels of water from the city government every week, but that doesn’t happen.

«The months pass, and there’s no [water] distribution. I call the city government and their response is that there is no water in the well; that there are no water trucks, that they’re broken down, that ‘it will be sent tomorrow,’ and it never arrives.”

Doña Rosalba

She normally spends $1000 pesos a month (around US$50) to get water from private trucks. Often that water is only good for washing clothes and dishes, since it isn’t drinkable; so Ms. Rosalba is also required to buy bottled water.

Her home is not within the area considered the “urban center” of San Salvador, which is a legally demarcated area. She is in agricultural lands she inherited from her grandparents. That’s why she hasn’t been able to connect to the infrastructure that is part of the public system run by SACMEX, nor has she been able to benefit from the Rainwater Harvesting program run by the Environmental Secretariat of Mexico City (SEDEMA).

“That’s why we are limited in our access to public services, we weren’t included in the program.”

There are hundreds more households just like doña Rosalba’s that are located outside of the urban area of San Salvador. There are at least 14 areas around the town defined as “irregular settlements,” which face problems of exclusion and inequality.

“City hall has been going backwards these last few years. The mayor didn’t carry out a single useful infrastructure project, and we don’t know how most of the budget was spent. But when there are elections, they pay attention to us,” said Rosalba.

The business of water

During the most recent elections in her borough, she said, the PRI and the Green Ecologist parties promised to repair the roads and give her a water tank. The rest of the candidates didn’t even come near her neighborhood.

In addition to the political use of doña Rosalba’s vulnerability, she found out that members of the city government in Milpa Alpa have played an important role in the business of selling water via private trucks in San Salvador Cuauhtenco.

Others interviewed for this article confirmed this situation.

Fernando, who is 29, does have a connection to running water in his household, which is located within official city limits. But for the last six years, there hasn’t been enough water for his family. He has to compensate by buying water distributed by private trucks. Between his payments to SACMEX and the water trucks, he pays around $1,100 pesos (US$55) per month.

The young man attributes the lack of water in his home to the growth of the population of San Salvador, as the land has been divided and sold at low prices. Milpa Alta is the borough with the third highest level of growth in single family houses in Mexico City, according to a census carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography in 2020.

Fernando explains that because territorial planning is so out of date, and because of the reforms to agricultural laws, they have not been able to increase the size of the urban center. Those who live outside of the official limits, like doña Rosalba, are those who suffer the most with regards to access to water. They are also the main consumers of water delivered by private trucks.

Fernando says the water trucks in San Salvador Cuauhtenco are sold by family members of bureaucrats within the municipality of Milpa Alta; and that they illegally siphon the water from the public system.

It’s something that we have noticed in our town, and no one does anything. We complain to SACMEX and they don’t respond. It’s not possible that there is a lack of water in the town, and these people sell water as if it was no big deal.

Fernando, resident of San Salvador Cuauhtenco.

The community lives the injustice and impunity linked to the de facto privatization of water every day, even though the Political Constitution of Mexico City stipulates that “the management of water will be public and not for profit” (Article 9).

Fernando has also been unable to access SEDEMA’s Rainwater Harvest program. A year ago he tried, but his roof didn’t meet the height requirements, which meant that installing a rainwater collection system was unviable.

In the periphery of the periphery

According to the records of Mexico City’s Systems for Rainwater Collection program, from 2019 to February 2021, a total of 20,193 water collection systems have been installed. Of these, only 151 have been installed in San Salvador Cuauhtenco. This means that not even one percent of the rainwater collectors have been installed in this community, which has serious problems in accessing hydraulic infrastructure. This leads to the question of the efficiency of the implementation of the priority selection criteria for accepting households into the program.

Another resident of San Salvador, who has asked us to protect her identity and who we’ll call C, doesn’t have water in her home. The 36-year-old woman built her home on land she inherited from her grandfather, and she doesn’t have access to public services. Her family gets their water from private water trucks, for which they pay around $300 pesos (US$15) every month. She said the person who sells her water lives in the center of the town and has a storage tank where they hoard large volumes of water.

The borough of Milpa Alta has said that because of a lack of water trucks, they can only provide the liquid via trucks to half of the population that lives in irregular settlements. They do so with trips that take place weekly, biweekly, every three weeks, or monthly.

“We only get a water truck every two weeks, or every month or so, it’s not enough,” said C.

In the areas without a connection to SACMEX pipes, says C, city hall tries to bring water every once in a while, but it has become politicized.

“There is a neighbor who gets water on Wednesdays, but when the elections happened they told her she had to attend the end-of-campaign event for the candidate, who is supported by people from city hall who are part of the Morena party. The neighbor refused, and up until today, she hasn’t received water. I was calling the office that takes care of water to ask for a water truck and they haven’t come.” C captures rainwater, but since her house is outside of the urban center, she wasn’t eligible for the Rainwater Harvest program. She built her own system with gutters, a tube and barrels. In her experience, those who get access to public programs are allied with the mayor.

Like Fernando, don Francisco, who is 58 years old, has a connection to the public water pipes managed by SACMEX. The water he receives, in addition to often being treated with bleach, isn’t enough for his family; as it only arrives every two or three days. In addition to using bottled water, he buys from private water trucks at least twice a week. He estimates that his family spends a quarter of their income on water, compared to the three percent ceiling recommended internationally. His family has never heard of SEDEMA’s Rainwater Harvest program, even though residents of San Salvador Cuauhtenco qualify for a complete subsidy, which means there is no cost for those who request to participate in this government program.

Francisco says that the water that is delivered to the community of San Salvador by private trucks comes from wells administered by SACMEX, but that it is extracted in secret.

“They steal it from Milpa Alta or San Francisco Tlalnepantla, Xochimilco. There are people who hoard water and sell it; for example, in San Francisco: they take 100 pesos (US$5) and allow the trucks to fill near Monte Sur,” a country club in Xochimilco.

Inequality: the more you have, the more water you get

According to Sacmex, the highest water consumption occurs in the areas with the highest level of economic resources, which are cataloged as having a high development index. In these areas, each home has access to around 2,000 to 4,000 more liters of water monthly than do households in poorer and more popular neighborhoods, like San Salvador Cuauhtenco.

Comparación de consumo por recibo por alcaldía en 2009 y 2017 en metros cúbicos, donde Milpa Alta es la de menor consumo, pero las cifras pueden reflejar la falta de acceso al líquido entubado.

The Mexico City Human Rights Commission (CDHCM) has documented the inequities in access to water. It contacted Leo Heller when he was the special rapporteur for human rights and water of the United Nations, to inform him that in some lower income parts of the capital it has registered between 28 and 67 daily liters of water use per person (under the 100 liters considered optimal by the World Health Organization). Meanwhile, in neighborhoods with higher wealth, the daily consumption can be over 800 or even 2,000 liters. SACMEX has reported that the 11 wells in Milpa Alta only produce 67 liters of water per day for each resident, and that that won’t change until there are resources made available to rehabilitate the wells in 2023.

A survey carried out by the National Institute of Geography and Statistics (INEGI) showed that 1.1 percent of households in Mexico City don’t have access to hydraulic systems, while in Milpa Alpa it’s 10.9 percent. The study notes that in San Salvador Cuauhtenco, 15.9 percent of households lack access. What’s interesting is that even though Milpa Alta has serious water supply problems, from 2019 to 2019 it had the second to least complaints (16 in total) for failure to comply with the human right to water and sewage removal at the CDHCM. The borough only had 1.4 complaints per 100,000 residents, which is why it is so important to spread information about this human right among the most vulnerable, as well as the forms it can be defended via corresponding authorities.

Various causes, one origin

Hydraulic injustices take place in part because of the origin of the liquid (wells, diversions, rivers); due to the quality and availability of the infrastructure; and the concentration of or the distance between households, among other legal, technical, budgetary, political and historical factors. The reality that the 29,000 households without a connection to running water in Mexico City face is connected to the quantity of water that is available in the territory. Access to water is tied in large part to the socioeconomic status of residents, which constitutes discrimination of their human rights. Without equity in public services, the most marginalized sectors are those who pay the social and economic consequences, which makes it more different to escape from poverty.

This context also reflects the incapacity of the state to guarantee another essential human right: that of dignified housing, which is what has led to the occupation of “unauthorized” or “illegal” areas. Mexico City’s Environmental Prosecutor for Territorial Organization has reported that Milpa Alta is the borough with the third largest number of irregular human settlements. Some of the reasons for this are the lack of a holistic housing policy, disorganization in urban planning, a lack of soil and water treatment in these áreas, as well as land speculation. The current regulatory framework in public institutions allows for the conditions of discrimination and inequity.

The problems with regards to the Rainwater Harvesting program in places like San Salvador have been known to the SEDEMA since the first year the program was implemented in 2019. In an internal evaluation document, SEDEMA clarified that “there is a considerable population that is vulnerable and lacks access to water that cannot participate, because they live on land demarcated for conservation, or they do not have the official documentation required.”

It would be possible to change this situation by seeking a writ of protection from Mexico City’s Superior Court of Justice in order to ensure access to the program to all of those who have been excluded.

If the government of Mexico City is truly promoting a “City of Rights,” SEDEMA and the government of the borough of Milpa Alpa could take on such a legal process, with the active participation of marginalized communities. Water, a public service and a human right, can be guaranteed through citizen empowerment.

Proposals

Making complaints to SACMEX or local authorities regarding corruption and illegal water sales is pretty much pointless. These institutions lack protocols and personnel that are trained to attend to these kinds of infractions; in addition, bureaucrats can also be involved, as residents of San Salvador have alleged. The Public Ministries and States Attorney Generals could help, but investigating corruption related to water is a new issue for Mexican authorities. In addition, these crimes are often not typified and there is a need for better proposals in this regard.

Community Participation

Accessible spaces where communities can participate, understand and attend to these problems together with local public institutions are needed. Communities have valuable information that could help to resolve their water problems. The lack of communication and contact between authorities and citizens is notoriously bad, which is why shifting the paradigm of public administration must include a territorial-participatory focus, which requires multidisciplinary action.

Collective citizen mobilization is needed so that the communities can change their contexts. This process requires dialogue, listening, organization, institutional connections, and the creation of agreements and follow-up on work plans which should be carried out in a multicultural, intergenerational and gender equitable manner in order to be inclusive.

Accountability

Another important element is pushing for most transparency, accountability and audits; especially in relation to water and sewage projects, the management of private water trucks, and the information regarding the debt that companies have with SACMEX (this was one of the reasons the current administration of Mexico City withdrew contracts with the companies contracted years earlier).

If these massive debts are paid up, there will be a larger budget to strengthen guarantees for the human right to water and sewage treatment. In addition, on the part of SACMEX there needs to be increased supervision in order to reduce leaks due to the deterioration of the water system, and to prevent the clandestine removal of water from the system or via wells. Complaint mechanisms need to be improved. The technology to detect leaks in the hydraulic system already exists.

It’s also important to fight against the political use of water, especially with government provided water supplies. In order to do so, it will be fundamental to establish a transparent and culturally acceptable system, which includes an equitable distribution calendar that takes into account priority areas. According to the reports available from the borough of Milpa Alta regarding the delivery of water by truck, in 2017 the town of San Salvador Cuauhtenco received an average of 187 trips per month, in 2018, 286, in 2019, 207, in 2020, 186, and in 2021, 220. There was no available data on water delivery by truck from SACMEX.

In addition, privately owned water trucks must be formalized, and carry registries of each borough, town and neighborhood. They must also have price ceilings, standardized water quality and reveal the sources of the water they are transporting. The Federal Commission for Protection against Sanitary Risks as well as the Consumer Protection Secretariat could play a role in this. Apps –which young people could help design and maintain– could also help with the social control of the water trucks.

Fetching water is a gender issue

INEGI’s 2017 Module of Households and the Environment (MOHOMA) shows that in Mexico, 33.6 percent of the population of localities with more than 2,500 residents (like San Salvador Cuauhtenco) that don’t have a connection to public water infrastructure get water from trucks, in these cases women spend four times longer getting water than men.

The MOHOMA also found that Mexicans who rely on water trucks spend $367.90 pesos on average (around US$18) per month; regardless. According to our investigation, this figure can reach over $1000 pesos (US$50) monthly, which is well over the three percent threshold recommended internationally to ensure the human right to water and sewage treatment. This indicates a lack of compliance. The MOHOMA also found that communities with over 2,500 residents also paid an average of $210 (US$10.50) per month for bottled water.

In the global context of COVID-19, Milpa Alpa was, for a long while, the borough with the most cases per 100,000 in Mexico City. It placed among 10 municipalities with the highest rates of transmission in the country, according to data from the Health Secretariat. Access to water is vital for lowering transmission of the virus, as it permits handwashing, cleaning, cleaning fruits and vegetables, and so on. At the same time it is important to note that other factors also contributed to transmission of COVID-19 in Milpa Alta, such as poverty, inequality, irregularity in water infrastructure, skepticism and the lack of care services, as well as exposure in centers of mass gathering, such as the Abastos Central Market, due to the agricultural character of the area.

Debido a los altos contagios en San Salvador Cuauhtenco, fue uno de los pueblos con atención prioritaria por parte de las autoridades de gobierno. Algunas de las personas entrevistadas y sus familiares se contagiaron del coronavirus, y todavía sufren secuelas; pero continúan con sus actividades laborales, ya que la necesidad económica es más grande que la posibilidad de recuperarse adecuadamente en sus hogares. Esta situación también muestra que todavía hace falta mucho por hacer en materia de los derechos humanos relacionados a un empleo digno y a los servicios de salud en la Ciudad de Mexico.

The high rate of contagion in San Salvador Cuauhtenco meant that it was one of the towns deemed a priority by government authorities. Some of those interviewed for this story and their families got the novel coronavirus, and are still suffering its effects; though they continue working as they have economic needs that prevent them from fully recovering at home. This situation also demonstrates that there is still a long way to go in order to achieve human rights related to dignified employment and health services in Mexico City.

The water crisis isn’t just a question of its availability and the quality of streams and springs. It can also be understood as a technical, institutional, and political crisis that is intrinsic to democracy. The complexity of hydrological problems aren’t just a question of infrastructure, rather, they are connected to diverse factors, as described above. Many of these problems are related to governance and the lack of integration of the sector. Solving them will require the participation of many stakeholders from different disciplines, including the local communities that, without a doubt know a lot about their situation. The most urgent issue is a paradigm shift with regards to the management of this essential liquid. Carrying on with a simplistic and limited technical vision based on a cost-benefit analysis won’t help at all.

#HydraulicJusticeForSanSalvadorCuauhtenco

Cuauhtémoc Osorno Córdova is a researcher and columnist who writes about water policy, the right to water and sewage systems.

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona