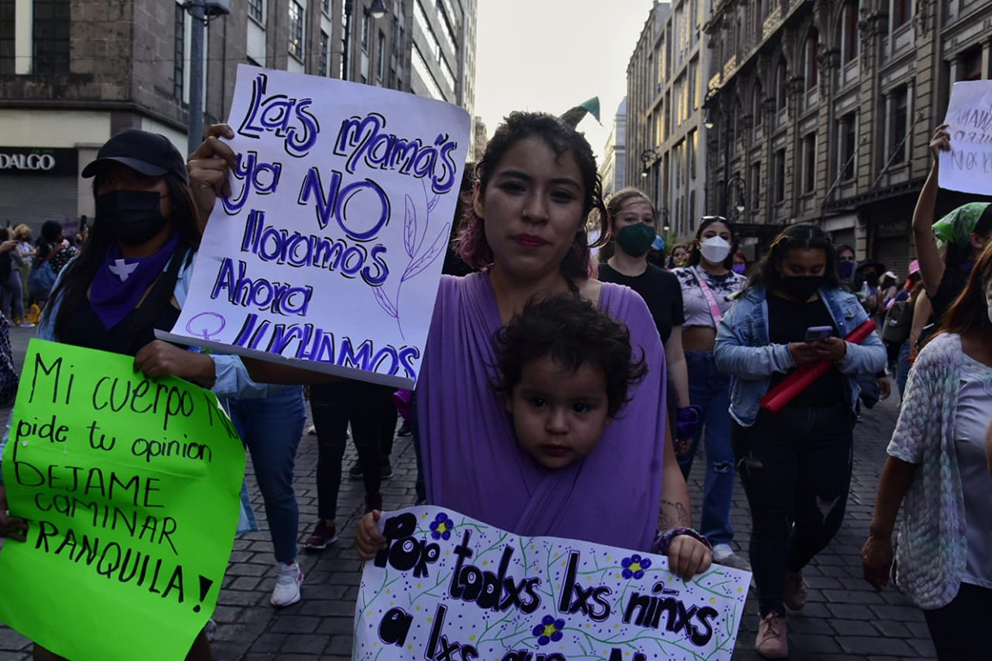

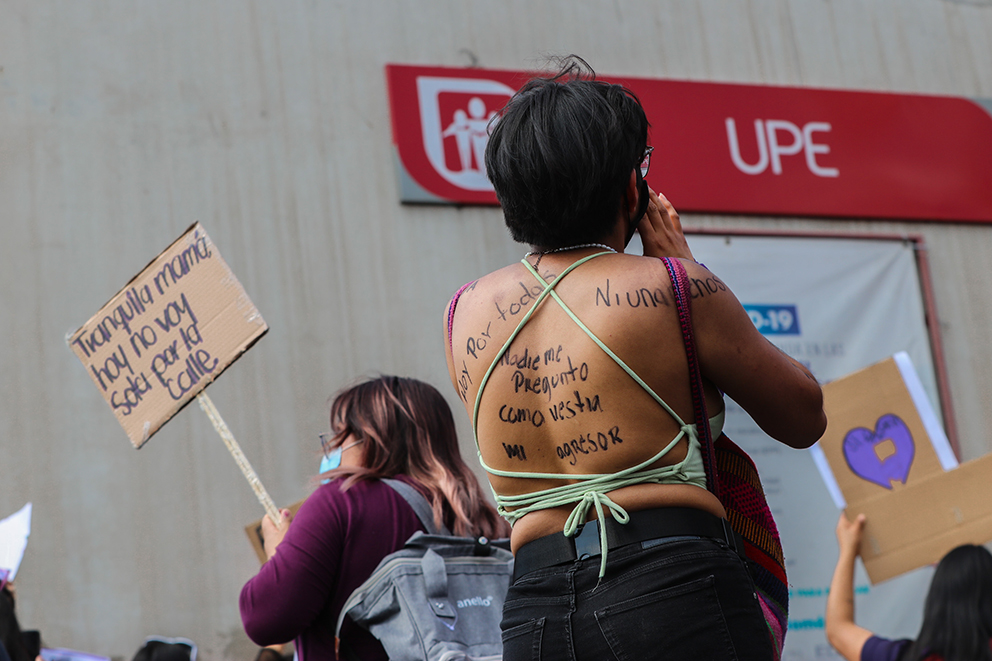

Going against predictions, the March 8th demonstrations on International Womens’ Day took place with one message: no to violence. Massive and diverse, the march in Mexico City put artistic expression out in front, and put a stop to transphobia.

Text by: Daniela Pastrana, María Ruiz, Daliri Oropeza, María José López, and Isabel Briseño, originally published March 9, 2022.

Photos by: Isabel Briseño, María Ruíz, Daliri Oropeza, María José López, Lilia Balam.

MÉXICO CITY—The predictions of violence were wrong. Instead of beatings and gas, demonstrators gave flowers to women police officers and the women in uniform joined the protest against gender violence.

The black bloc, a central figure in womens’ protests since 2019, was reduced to a single image: a broken window at the Hidalgo metro station. The new protagonist was the Jefa Andrómeda (Karen Ortíz), the feminist police officer who received accolades upon arriving to the Eje Central where she raised her left fist and yelled: “Consciencious policewomen, join the march!”

Nor were there separatists. The March 8th demonstration stamped out the transphobia that has been growing over the past months. Among thousands and thousansds of women that painted the emblematic Reforma avenue purple, it seemed like no one cared who was trans and who was cis, or who was Indigenous, or from what neighborhood folks came from.

The drums beat for more than 5 hours. And women of all shapes and sizes chanted, danced, sang and hugged. Workers walked with retired women. Students. Mothers. Daughters. Sisters. Activists. Artists. Journalists. Women in wheelchairs. All with a common cause: to call out the patriarchal order that oppresses and kills us.

“Mexican women to the war cry, to the sisterly roar of love,” said a message on Instagram that summed up the energy in the streets.

It’s the march of sisterhood. After two years of the pandemic, and under the heavy weight of unreleting violence, of government warnings and of the transphobia that’s become manifest in some feminist groups, pain and anger were transformed into thousands of creative signs and slogans.

Against Fear:

“You planted fear, I grew wings.”

“Me sembraste miedo; me crecieron alas”

Against stigma:

“We are bad, we can be worse. And who ever doesn’t like that can go fuck themselves, go fuck themselves.”

“Somos malas, podemos ser peores. Y a quien no le guste, se jode, se jode”

For historical memory:

“May the machos tremble, tremble and tremble, all of Latin America will be feminist.”

“Y tiemblen, y tiemblen, y tiemblen los machistas, América Latina será toda feminista”

For sisterhood:

“Take it easy, sister, your people are here.”

“Tranquila, hermana, aquí está tu manada”

For freedom:

“Mom, today I feel free.”

“Mamá, hoy me siento libre.”

On the peripheries: “Young women resist”

The occupation of the city started on the weekend, when a clothesline where women hang denunciations of abusers and violent men (un tendedero) was installed at the Anti-monument of Women who Struggle, and the inauguration of the Resistance Space of We want to be Alive Neza. On Tuesday, in San Cristobal Ecatepec, in Mexico State, the entity with the highest number of femicides in the country, the march started in front of the Iron Bridge, in the middle of honking trucks traveling up and down Morelos Way.

Families present said two men convicted of femicide are about to be released from jail. “There’s not much we can do,” said Sacrisanta Mosso, the mother of Karen and Erick, who were killed more than five years ago in Tulpetlac.

The women form a chorus, and sing in a circle. “They’ll come back, you pay for the blood you spilled, the women you killed will never die.”

The demonstrations grew. In the afternoon there was another march against the killing of Atena, a 13 years old who sold candy with her grandmother in the Fovissste Residential Units.

Outside of Ecatepec’s City Hall, Claudia takes the microphone. She’s the mother of Fernanda, a criminology student killed in the CTM neighborhood. Angélica says they have changed the investigation files and that the person who is now responsible for the investigation into the murder of her mother and sister. Alejandra, Paola’s mother, says that they left her naked body out after killing her.

“In Ekatepunk, young women resist” said the sign a young woman carried from the Iron Bridge to city hall.

These are the marches in the peripheries that rarely connect with the protests on Reforma avenue.

Around 50km south of Ecatepec, in a rural area of Mexico City, 50 women left the Xochimilco sports complex towards sites that represent systematic violence against women. The “walk of the flowers,” convened by the Coordination of Pueblos, Indigenous neighborhoods and sections of Xochimilco, revealed various forms of violence: sexual abuse, negligence, assaults in public transports, attacks on land defenders.

The walk ended on the esplanade of Xochimilco’s City Hall, where participants denounced that bureaucrats ignored their demands and facilitate displacement, inequality and danger in their communities. After putting their signs up on the temporary fences erected to protect the main building, the women from Xochimilco planted seeds and flowers in the garden area behind the statue of Emiliano Zapata and Francisco Villa, emblems of a struggle that hasn’t ended.

“We are plant women, that push through cement, that care for the earth and that harvest your food.”

Mothers: “Struggling for life”

This year, the mothers of victims of femicide were not at the head of the march, which seemed to overflow itself.

The start time was 4pm, but many groups of women arrived much earlier and started marching autonomously.

The mothers, who are used to walking in a contingent, waited until the agreed upon time. But the march kept moving.

They began to walk with the faces of their daughters on posters or in photos. José Luis Castillo, father of Esmeralda Castillo, who disappeared in Ciudad Juárez, joined up with the Aainja drumming group.

As we walked towards the Zócalo, many waved out their windows in solidarity with the families.

“Please stop the sound truck through so the mothers can be heard” said one, in the middle of all the people and sounds filling Mexico City’s central square.

The mothers were surrounded by a circle of women shouting “You’re not alone!”

Patricia Becerril, mother of Doctor Zyanya Figuero, took the microphone as Araceli Osorio, mother of Lesvy Berlin, lit incense on the offering that was carried out as a final ritual.

“I don’t know what’s going to stop me, or if something will stop us, but I can assure you that we’re in struggle, sometimes sustained by the hands of our youth, of our women. Thank you so much. We must continue to struggle for life,” she said to the women who listened attentively.

Many of the marchers traveled from other states to name their pain and demand justice, just like they do every day, but together with thousands of other women who yelled “Justice!”

“We’re back, we’re stronger”

The winds of freedom carried across Mexico on March 8th. In Guanajuato, thousands of women and children rebelled against a conservative society and took to the streets, demanding their rights to life, to education, to a dignified salary, to justice, to maternity, and to the right to decide about their bodies. The key cities in the state (León, Irapuato, Celaya, Salamanca, and the capital, Guanajuato), played host to large mobilizations, made up mostly of young women, and for the first time there were also marches in Apaseo el Alto and Cortazar. The pandemic set the struggle for gender equality back decades, but “we’ve come back even stronger after being shut in,” said the women.

In Merida, Yucatán, where feminist struggle was born over a century ago and where young Maya women continue to resist the loss of their language and culture, the women intervened in five statues: the statue of Montejo, criticized for being a racist symbol; the statue of Andrés Quintana Roo, located in Santa Ana Park; the statues of Felipe Carrillo Puerto and Justo Sierra, and the Monument to the Fatherland. They read a pronouncement in Spanish and in Maya to denounce various kinds of violence women are subjected to.

In Guerrero, one of the states with the most gender violence in Indigenous communities, there were marches in all of the regions for the first time. In Chilpancingo, the capital, a group of women carried a banner to the capital that read: “Women in resistance against sexual assault in schools.” Girls led the contingent. “May they have all that I didn’t,” read the sign of one woman who was waiting for the youth contingent.

In other places, the demonstrations were accompanied by concrete actions to recognize the memory and the history of womens’ struggle.

In Chihuahua, part of Marisela Escobedo’s story (she was killed in 2010 in front of the state legislature while demanding justice for her daughter Rubí) was painted onto a mural on the outside of the Center for the Human Rights of Women.

In Sinaloa, activist Mirna Medina, who is part of the search collective Las Rastreadoras de El Fuerte, founded after the disappearance of her son, received the Norma Corona Sapién Medal of Honour, which was created by state deputies of the 64th legislature. Legislators also approved abortion up to 13 weeks into term.

Diversity: “We’re so powerful that they want us divided”

Mary Saenz, who is from Veracruz, arrived at the Zócalo in a white dress with a long train that she herself sewed. She walked through the police lines with a Mexican flag in hand. She said she was demonstrating for all of the women who have been killed and violated. Her performance seeks to represent the tarnished motherland.

It was impossible not to turn and look. Her image was one that represents perhaps the central characteristic of 8M in Mexico City: diversity.

As the enormous purple snake crossed Reforma Avenue, there were Indigenous women, Afro-descendent women, people from different social classes, women using walkers and wheelchairs, women with kids in their arms or in strollers, lesbian couples or trans folks or gender fluid adults and children. Sex workers, electricians, unionists. No one rejects them. No one gets upset. The main message seemed to be: unity.

At night, after the mothers finished giving their testimonies, small bonfires are lit in the Zocalo.

“This fire is for everyone who should be here but isn’t,” said the women witches who danced around the fire and did performances about femicides.

Later, they repeated slogans in support of trans resistance: “We’re so powerful that they want us divided.”

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona