Sixty-five percent of the minors who disappear in the city of Puebla are girls and women, and civil society organizations have pointed to trafficking with the aim of sexual exploitation as the main reason. In 2019, Puebla city ranked first in the disappearance of children and adolescents in the country, and the state’s Search Commission failed to execute its full budget

Text by Aranzazú Ayala and Román Huerta, published by Lado B on May 24, 2021.

Edited by Mely Arellano.

Visual material by Gogo.

Translated by Dawn Marie Paley.

Victoria Rosales had no idea how many adolescents had disappeared in Puebla, until she found out in the worst way possible, when her 17 year old daughter Nadia disappeared on Friday October 27th, 2017.

That day, like any other, she went with her daughter to a stop of the Ruta 5, a few streets away from their house in the Lomas de San Miguel neighbourhood in the south of the city. She watched as her daughter got on the bus and waved goodbye. By 2:30 that afternoon, Nadia should have been home from school, but she never arrived. That, says Victoria Rosales, is when the ordeal started.

The year Nadia disappeared, the capital of the state of Puebla was in second place nationally in the disappearance of girls, boys and adolescents. Things haven’t improved since then, in fact, things have been bad for a long time: the disappearance of minors isn’t new, though it is still a problem that isn’t well understood.

Between 2012 and 2018, the municipality of Puebla had the second highest number of disappearances of people between the ages of 0 and 17 years old in Mexico, according to the Network for Childrens’ Rights (REDIM), which is based on the National Data Registry of Disappeared and Missing People (RNPED).

By 2019, the city had become the worst on a national level, that year 389 minors were disappeared, or at least, that was the number of investigations into the disappearance of a minor opened that year. In 2020, Puebla was ranked third nationally for most minors disappeared, according to the National Search Commission (CNB) and the Department of the Interior (SEGOB).

Of course all disappearances are alarming, but those of children and adolescents have to be investigated in a particular way, because of the age and the stage of development the victims are at. They deserve holistic protection, according to Juan Martín Pérez Garcia, who is the ex-director of Redim (his term ended May 14th). Any interruptions or impacts stemming from such an experience could have negative repercussions that last the rest of their lives.

In an interview with Lado B, Pérez Garcia explained how, compared with adults who can “decide to leave, minors cannot be without the protection of their family network and their legal guardians,” because they are “vulnerable to adult power” and can become “objects for sale” for sexual and or labor exploitation or illegal adoptions, among other things. That is why the state has the obligation to fully protect them.

One more bit of information can help contextualize and understand the size of this problem: in Puebla, 65 percent of minors who have yet to be located are girls and teenagers like Nadia, whose family has received multiple reports that she has been seen in prostitution zones in other states, but “the Attourney General hasn’t done anything.” In the three and a half years since she was disappeared, there are few leads in the investigation.

Attorney General, Absent and Ignorant

Three years have passed since Nadia Guadalupe was disappeared, and there’s still no Amber Alert in her name. Just eight months ago, the new investigator –the fifth since the case was opened– that the State’s Attorney General (FGE) assigned to investigate the case began to send the paperwork seeking collaboration with other states in the search.

It bears repeating: it took the FGE more than three years to send the paperwork. In addition, the family has still not been told why an Amber Alert was never emitted. Victoria Rosales recalls that the Public Ministry told her that Nadia “wasn’t in danger” because she “doesn’t have the profile for human trafficking.”

The Amber Alert is a mechanism within the state’s jurisdiction, and when a minor disappears they are obliged to immediately enact it, because it sends a missing person bulletin to the national level and activates collaboration with all of the states in the republic.

But though Puebla is one of the entities with most disappeared children, the mechanism is not always applied. According to information from the CNB in its April 2021 report, 62 percent of disappearances of minors take place in one of seven states in the country, one of which is Puebla. Regardless, the Amber Alert isn’t always activated.

According to information published by Puebla’s Attorney General, “the diffusion of the Amber Alert in Puebla takes place through the online portal and official social media accounts, as well as by authorities, civil society organizations and media, via official information.”

According to a review of the FGE’s Twitter account, only 28 Amber Alerts were emitted for disappeared minors in Puebla between 2015 and 2020, far from the total of 479 children and adolescents who have yet to be found, according to the same office. In other words, only 5.8 percent of the cases were published on the social media of the government entity.

The Voice of the Disappeared in Puebla collective told LADO B that the FGE often fails to create the bulletins, that it does not publish them online or share them publicly, arguing that they do so in the interests of protecting the minor. In fact the collective is aware of various cases in which authorities from the FGE told family members of the disappeared not to approach the media or collectives, because they “will complicate the case and put the person at risk.”

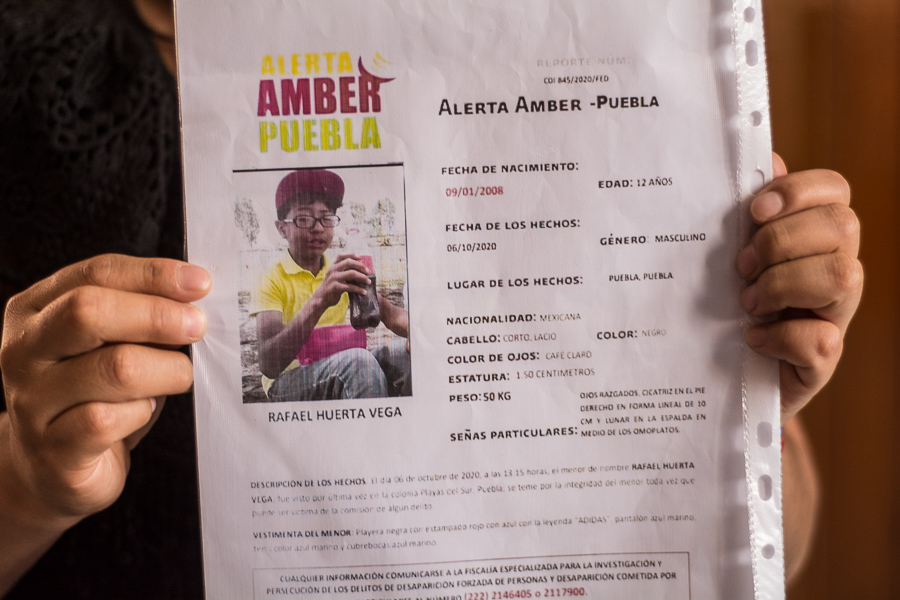

But just emitting the Amber Alert isn’t a panacea, as Teresa Vega, mother of Rafael Huerta Vega knows all too well. Rafael disappeared on October 6, 2020 at the age of 12, in the Playas del Sur neighborhood, when he was believed to be on his way to the store. Though she reported the disappearance that day, the Amber Alert wasn’t activated until three or four days later.

Just as in Nadia’s case, the investigation hasn’t made significant progress. Rafael’s mother hasn’t even been allowed to see the case file, which has been denied to her, on the grounds that it is a “private investigation,” nor has she been allowed to make a complaint against the father of her son, who lived with the boy when the disappearance happened, so that they can investigate presumed mistreatment of the minor.

Teresa Vega and Victoria Rosales agree that the State Attorney General not only doesn’t do its job, but in addition, they say that the police officers berate them, they don’t explain things to them and are rude, and that officers have slyly accused them of being responsible for the disappearances.

And if with regards to investigation the authorities are inefficient, in terms of prevention they are even worse.

There’s no officials at any level who are working on the prevention of disappearance of youth and children. It’s not a minor oversight if we consider that, according to Redim, the disappearance of minors in Puebla is linked to human trafficking and sexual exploitation.

A search commission that doesn’t search

The obligation to search for the disappeared and investigate such cases, including those involving minors, falls to the FGE and the state government, vis a vis the State Search Commission.

Puebla’s State Search Commission was created in June of 2019 as “an autonomous branch of the Department of the Interior, with technical and managerial autonomy, in charge of determining, executing and following up on the work of searching for, finding, and identifying disappeared and missing people in the state of Puebla,” according to its website.

However, the lack of a real effort in searching for the disappeared is revealed, according to the president of the Commission of the Family and the Rights of Children of the Congress of the State, congresswomen Mónica Rodríguez Della Veccia from the National Action Party (PAN), by the fact that 10,000,000 pesos from the budget were not used in 2020 and had to be returned to the federal government.

Mónica Rodríguez brought that information forward to María Teresa Castro Corro, Puebla’s Secretary of Planning and Finance, during her testimony on January 22nd. But it turns out it is not completely true, because according to document RRA 03827/20, available on the National Transparency Platform, the under-execution of the budget took place in 2019.

Puebla was one of 20 states which did not spend a federal subsidy of 248,881,652 pesos, and had to return its part, 10 million pesos, to the federal government in 2019, the same year that Puebla City was first nationwide in terms of the disappearance of minors.

LADO B sought an interview with the Puebla’s State Search Commission to see if there is a specific protocol that is followed in searching for minors, as well as to get clarity around the budget issue. There was no response before this article was published.

There are other institutions which also play a part in searches for the disappeared, such as municipalities. In accordance with the Victims Law of the State of Puebla, municipalities must guarantee, together with state authorities, a rapid investigation, reparations for damage, to seek to uncover the truth, to provide protection on the part of the state, and to provide efficient, agile and transparent access to the justice system.

So far this year, the Municipality of Puebla has attended to 95 calls for assistance in accompanying and carrying out searches on the part of the FGE and Puebla’s State Search Commission.

The City of Puebla has a specialized group dedicated to searching for disappeared women, children and adolescents, which depends on the Municipal Department of Governance, whose functions include assisting in the search for minors. It was created on July 12, 2020, in accordance with to the fifteenth point of Justice and Reparation described in the Declaration of the Alert of Gender Violence against Women (AVGM) in the State of Puebla.

This organization allows for collaboration between the three levels of government and distinct dependencies. For example, the state government can seek support from sniffing dogs or from specialists to accompany a search, or with the publication and dissemination of images.

Disappeared children: who, why and how many?

To begin with, there aren’t even trustworthy numbers of how many minors have disappeared, nor do we know why they were disappeared. Civil society organizations take their numbers from the RNPED, but its methodology changed in April of 2018 and it became impossible to view information at the municipal level, regardless of the insistence on the part of activists and journalists.

Between 2015 and 2020, according to information from the FGE released through transparency reporting requirements, in the city of Puebla there are 1,620 disappeared, of which 479, or 29 per cent, are minors.

Of the children who remain disappeared, 314 are girls (65 per cent) and 165 are boys. The age group with the most disappearances among young women is 15 year olds, followed by 16 year olds, 14 year olds, and 17 year olds. The tendency among young men is similar, the most common ages for disappearance are between 14 and 17, though it is much less common.

The analysis of these numbers shows that adolescent women are the most vulnerable to disappearance, presumably for being potential victims of sexual exploitation.

In 2018, the National Association against Human Trafficking (ANTHUS) found that Puebla city was the first site nationally in the traffic of minors.

Juan Martín Pérez Garcia, who is a member of REDIM, thinks that the disappearance of children and adolescents [in Puebla] is primarily connected to human trafficking with the potential end goals of sexual exploitation or labor exploitation. According to his analysis, this is so because of the closeness to the Puebla-Tlaxcala corredor, one of the most famous, if not the most famous, for sexual exploitation, especially of women, and of minors in particular.

Regardless of these warning signs, the numbers indicate that things remain the same, and that the risk of disappearance continues to be high for minors in the city of Puebla.

According to an analysis of information obtained by the FGE, LADO B found that the second most common ages for disappearances in Puebla are newborn babies and children under 3. For the most part these are connected to custody battles, in which fathers or mothers remove the minor without the consent of their partner, according to Marisol Casillas Hernández, a therapist who is in charge of statistics for the Mexican Association of Stolen and Disappeared Children.

No support for families

In 2019, Puebla’s state congress approved the Victims’ Law, which enshrined the centrality of children in decisions regarding support, protection, immediate help, lodging, and the right to truth for victims of kidnapping, enforced disapperance, human trafficking, torture, and other cruel treatment, suffered by too many over many years in the state.

Regardless, mothers, fathers, and family members of children and adolescents have stated multiple times that the authorities do not help them or follow up on their cases. This is why they have had to join organizations or create collectives in which they can continue their searches.

This report was originally published by LADO B, which is part of the Media Alliance organized by Red de Periodistas de a Pie. You can read the original here.

Click here to join Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona