Street-involved women create bags and kerchiefs for economic stability at a silk screening workshop in the municipality of Venustiano Carranza, in Mexico City. The workshop is also a place to learn about feminism, a safe place where they can talk about the violences they’ve experienced and learn the meaning of sisterhood through lived experience

Text and photos: María Ruiz, originally published March 19, 2021

Translation: Dawn Marie Paley

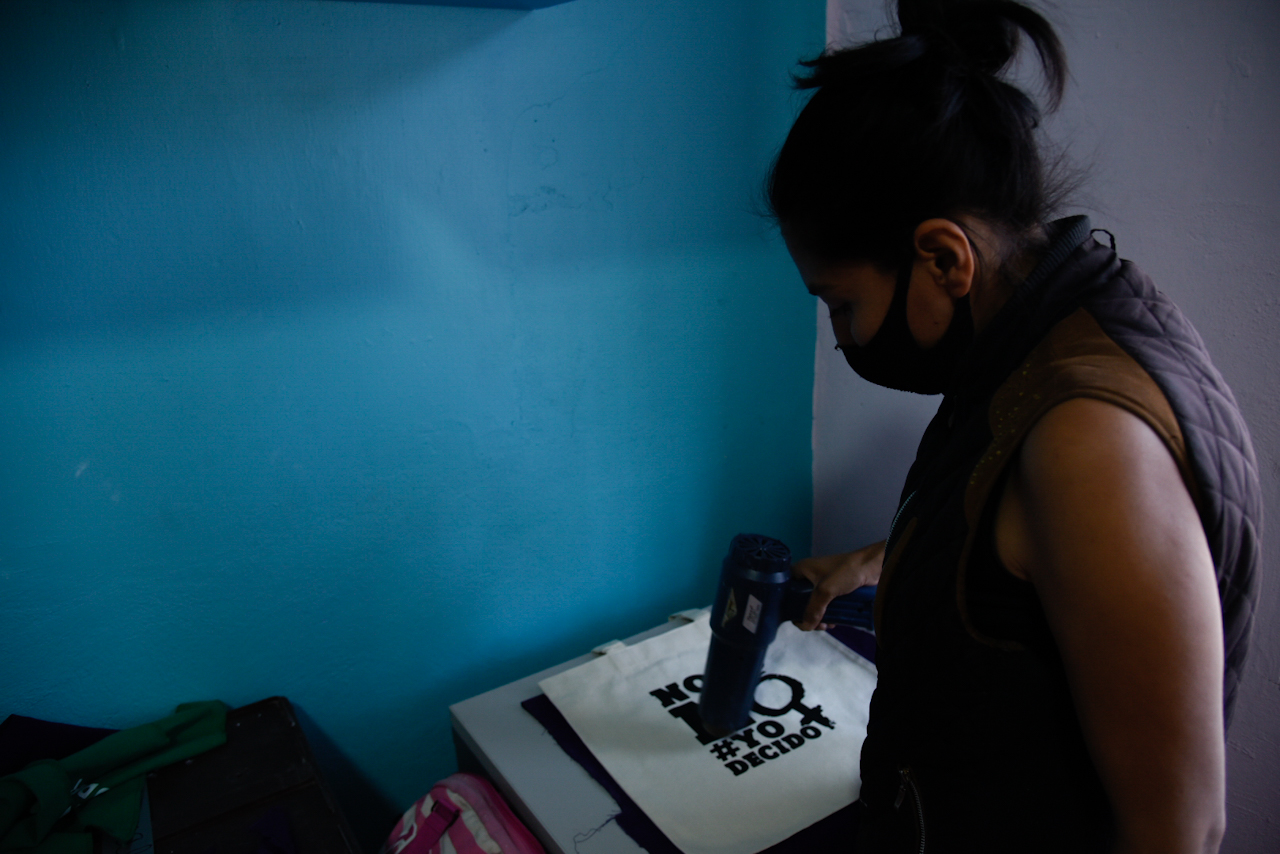

MEXICO CITY.– In a room transformed into a workshop, in front of a large window overlooking the street, two screen printing machines await use. In the corner, a filing cabinet has become an ironing board. Over the month of March, this room became a workshop, and the workshop became a place of encounter for street-involved women.

Between these four walls, with banda music playing in the background, they created bags and kerchiefs to sell during the women’s march on March 8th. The workshop is meant to give them an option for work in which they are paid daily, as well as serving as a source of information on women’s rights. The slogans they printed onto the cloth, like “no is no, I decide,” and “my body is mine,” caused them to reflect on their rights and the violences they experience.

The youngest women are under 20 years old. Mariana, 14, became a mother to Mateo a month ago; Vanessa, 17, is four months pregnant. The oldest are in their 30s: Karla, Mariana’s mother, and Susana, who has been working with El Caracol, an organization devoted to fighting for the rights of street-involved people, for the last six years.

“My body is mine.” That slogan, which is often heard at the marches of women fighting for the right to legal abortion world wide, generated contraditory opinions among them, but after discussing it among themselves, they arrived to a conclusion: they would support their compañeras no matter what decision they took. And they wouldn’t judge if they decided to become a mother or to have an abortion.

“No is no, I decide.” Another common slogan, which graced the pink shirts that all the women from the workshop wore to the march. It reminds them of their right to a life without violence.

This year, 2021, was the second year that they sold kerchiefs and bags before and during 8M, as International Women’s Day is referred to in Spanish. But because of the pandemic, and in order to respect health requirements and avoid infections, they couldn’t be more than four.

“The idea of the workshop is that they don’t have to work in the metro or in the trollies selling sweets or cleaning, for two reasons: one, because those spaces are among those which have the least possibility of social distance, where there are the greatest chances of getting Covid-19; and two, so that they have a stable income in a secure place where they’re making their own products and where their kids can be with them, because [otherwise] their kids have to go with them to the metro and that’s very dangerous for them, they could get taken away or they could call,” said Alexia Moreno, the coordinator of El Caracol.

***

It’s the last day of the workshop and the women easily use the screen printing machines. Karen and Georgina, together with members of the organization El Caracol, move their hands over cloth and paint. They complete the pieces perfectly, with no spots. Their plan is to arrive at the Revolución metro stop at 10am on March 8th and start selling.

They’re good at selling. Most of them have worked in sales at some point in their lives, selling in the metro, or at stoplights. They’ve been abused by police who think that because they live in the street and they work in the informal sector they don’t have the right to privacy or to say no.

By the end of the day they had sold around 100 kerchiefs and had around 15 bags left over. In El Caracol, they’re already thinking of how they can evolve their technique to continue to produce merchandise. Their intention is to begin to sell in small feminist markets, women organized tianguis (temporary street markets) where they hope to build their networks.

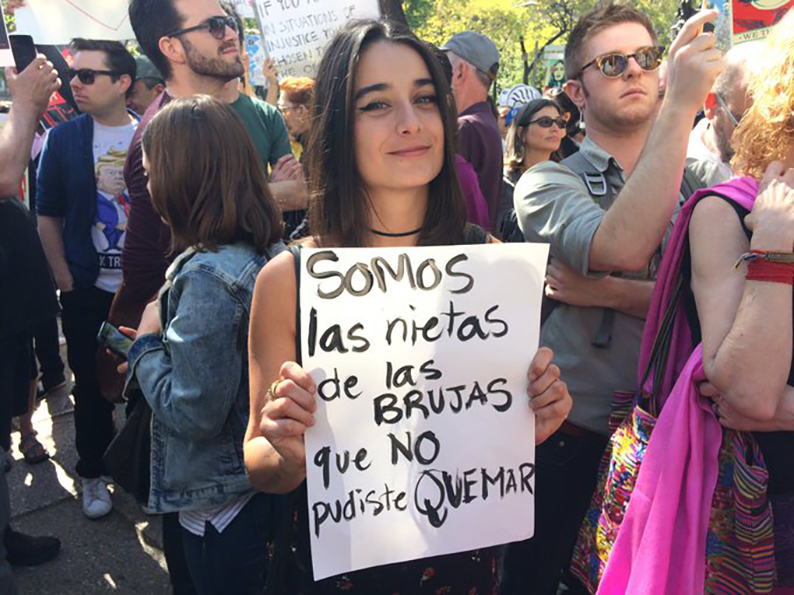

This was the third march they attended as the “Amigas en el camino” collective. The first demonstration they participated in was on November 25, 2019. On that day, Susana spoke on behalf of herself and her compañeras: she asked that they not be judged, nor invisibilized, for living in the street.

The next year was different. In the largest women’s march in the history of México, among the purple crowds in the open space of the Zócalo, Susana González felt hurt. Together with her friends she asked for permission to go up on the stage and name the violence that street-involved women face, but they were refused.

“We also want to be listened to, we want to be understood and to be taken into consideration, we don’t want to live in the shadows of the city. You are in our house, because our house is the street. You came into our home and you refused to let us express ourselves up there [on stage], the lack of support between women is no good, and that’s one example of how when you are from the street, you can’t express yourself,” said Susana in a recorded communiqué the group helped her prepare.

For El Caracol and for Susana, that 8M they were discriminated against by the feminist women who oversaw the stage. Susana said to them: “‘Why are you doing this? Are you saying that because I live in the street you won’t let me up [on stage]?’ And then when they saw that I was upset they were like, yes, ok, you can go up in a minute. But they never let me. So I say, it’s no good that one woman discriminates against another.”

Alexia Moreno recalls that they were told “you’re not going up because you’re not a victim,” and she asks: “Let’s get this straight… Living in the street, they have their kids taken away, they experience police violence and sexual abuse, what else do they need to be victims? To be killed? Because they’re also being killed.”

On that same 8M, “Las Casitas,” as they call their homes in La Raza metro station, were in mourning. During International Women’s Day last year, two women were killed there.

Vanessa, who is active in the silkscreening workshop and also lives in Las Casitas, wasn’t familiar with feminism, but the femicides in her community exposed her to injustice.

“I attend the march for one reason: because my aunt was a victim of femicide. She wasn’t my aunt aunt, but she was a person who was very loved, who lived in Las Casitas. Her name was Ana Laura.”

Ana Laura was killed by the father of one of her friends. He also had problems with his daughter (Ana Laura’s friend). On March 8, 2020, he took out a gun while they were hanging out. Ana Laura tried to stop him and he killed her. Then he killed his daughter and his son-in-law, who was also present. A year after the multiple homicide, he has yet to receive a sentence.

“My good friend was murdered a year ago and we have another good friend, Thalía, who was murdered almost three years ago. She was a lesbian who lived in our community. She was such a lovely person, she lived with her partner. [One day] everyone went out to work and someone who had just come out of prison went to Las Casitas and, since she was alone, he tried to force her to sleep with him. She didn’t want to and he beat her up. She was in pain for a few days, and her organs failed, that’s how Thalía died. There’s another friend of ours who was raped. She went to the police and they said no, because she lives in the street she was guilty and she couldn’t file a police report,” said Susana.

Double discrimination

Susana is 39 years old. She has dark skin and her black hair is very, very long. She is physically strong, and so is her character. She worked as a faquir in the metro, where she would accost herself on broken glass, until her daughter saw her bleed and became very scared, that’s when she sought another way to make money.

That’s when she started to exercise and broke with one of the beliefs that many women have: that we’re weak. Chin-ups became her specialty, she went into the metro and did them on the handrails as the metro sped along. Passengers gave her money because as a woman she “surprised” them with her “unusual” strength.

She had her first exposure to feminism in El Caracol. Of all the women that worked in the workshop, she’s the only one that explicitly identifies as feminist, which is why her demands and her way of speaking are so clear:

“We suffer double discrimination. First, for the simple reason that we’re women and second, because we’re from the street. Discrimination in public spaces, from our partners, in our community, and logically, we don’t have our families. They think that we’re stupid, that we’re dirty, that we’re bad mothers, ridden with vice. So what we ask is that before they judge us, they hear our stories. That they learn why we’re in the street.”

Many of them left their homes because of violence they lived in their direct family. Rape, beatings, abuse. At 16, Susana was abused by her older brother. He spied on her, he hit her.

“I have a seven year old daughter, her name is Melanie. I want her to learn to defend her rights. To not be walked on, to not stay silent, to speak. I remember when I told my mom my brother spied on me and touched me, she got upset with me and supported my brother. I don’t want that for Melanie. I’ve told her: you’re going to have my support, and you’re a strong woman, with or without me. I try to tell her not to be aggressive but also, not to get used. I didn’t have that, I want to give her the tools she needs and I think that’s what this movement is about, to give these tools to them, the youngest ones,” she said.

Karla and Mariana are clear about the violences they have survived. Karla lived with violent partners, when Mariana was three months old she left Mariana’s father because he was hurting her. Mariana, who is 14, has never said she’s faminist but she knows she will not tolerate any more violence. Four months ago she separated from her partner, who physically hurt her.

“I didn’t say anything the first time. The last time he attacked me it was a lot. You hit your limit and you draw the line. I decided to leave because of my baby. My son’s well being comes first,” said Mariana.

Karla says Mariana arrived heavily injured, “macheted.” As a mother that hurt, it made her think of the patterns that are repeated, and she warned her daughter. She told her she would support her if she filed a police report.

“I lived through it in the flesh. I said, don’t be like me, because I lived through all that, and you witnessed it. And I don’t want your son to see that because since he’s a boy, he’ll copy it,” said Karla.

Since then they’ve lived together. For them both, the arrival of Mateo has meant a search for stability and safety. Both are taking steps to get there. Mariana left the partner who abused her; Karla got clean. In March they went to the workshop together, and the day of the demonstration, Karla stayed with Mateo so Mariana could march.

“Feminisms never talk about us”

This year, less street-involved women marched than last year. The pandemic has also impacted them. There is less work, many went back out on the streets or back to their families in other states. There were about 15 people in their bloc, between the educators at El Caracol and the women who live in the street.

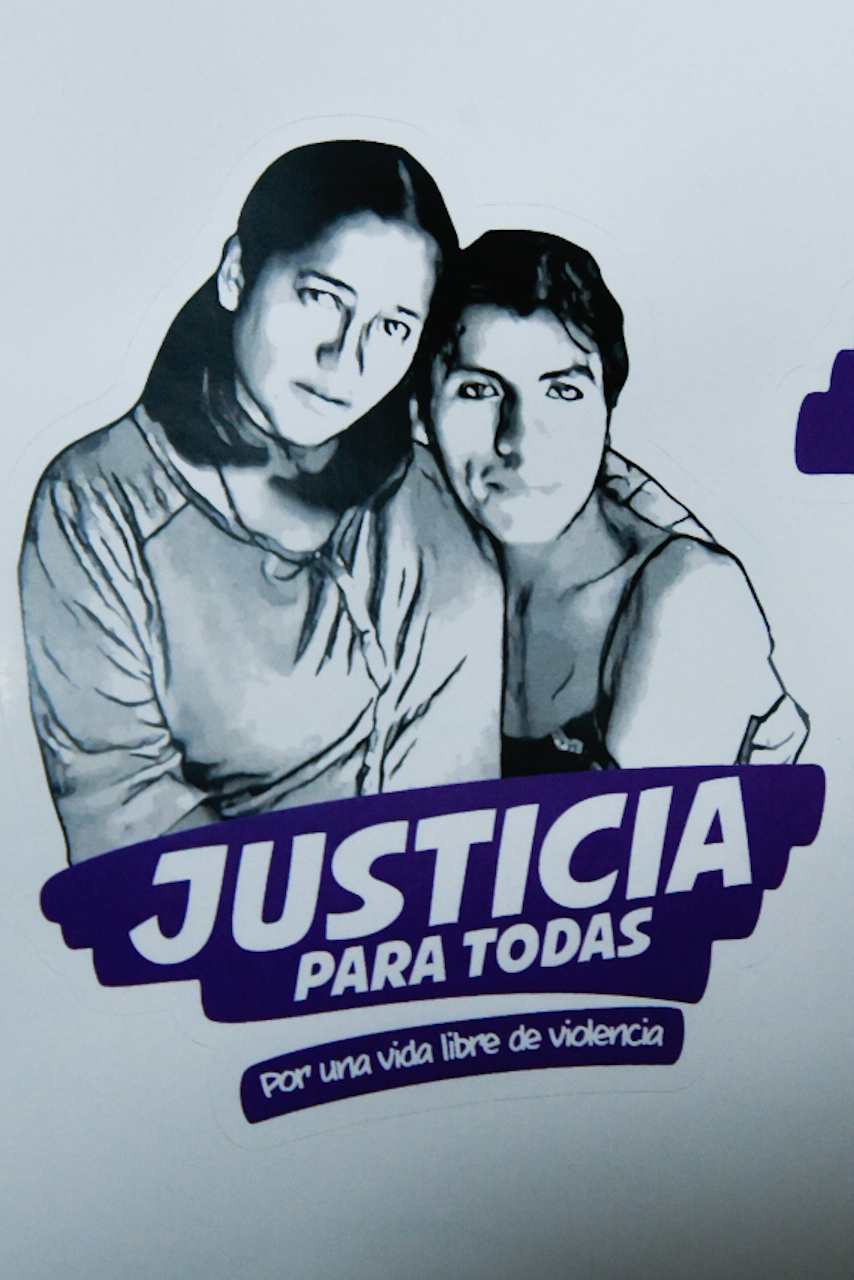

The week before the march they took another workshop, about stencils. They created the stencil from photographs. They also made stickers. The most important sticker was one that said “Justice for all women. For a life without violence” on a purple banner under the photo of two women hugging. The two women are Ana Laura and Thalía.

The day of the march Susana led the chants, they filled the streets with stencils and painted Ana Laura’s name on the memorial to victims of femicide on the temporary walls put up around the National Palace.

Then came the reflection, they told the stories of the woman who had been found dead outside the metro. They cried, because when they marched they did so knowing that they weren’t all there, that Ana Laura and Thalía are missing, together with many other women who have died in the streets, and whose deaths aren’t even recorded.

For El Caracol, it’s extremely important that they are part of the women’s rights movements. According to Georgina Navarro:

Feminisms never talk about women who live in the street. It is fundamentally important that they have political agency, like any other woman, because they are excluded in many ways, but they also have the right to raise their voice, to participate in this historic march.”

Susana has never liked injustice, rather, she likes to help people. Feminism has become a tool to help her achieve that, a way to learn together with her compañeras.

“Normally everyone scratches their own itch, and here, what I came to learn, was solidarity. Not just the solidarity that helps you as a person but the one that helps between two women. This is something really special that we take with us. If I see a woman with a problem, I will go to her and say “Can I help you with that?” So that’s how it is, we look after each other. I wish feminism would allow us to express ourselves, so that they can understand us, not judge us, so that we can explain to them why.”

María Fernanda Ruiz is always an outsider, audiovisual is her jam, and journalism is the path through which she understands and questions the world.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona