The cruel violence used by groups that recruit youth and police hasn’t slowed, according to researchers; a week after the elections people in the state are living through days of massacres and political killings.

Text: Verónica Espinosa, originally published by POPLAB on June 16, 2021.

Illustrations: Juan José Plascencia/PopLab

Children have been impacted by criminality that moves amid the absence of coordination and of official policies meant to stop it; youth are becoming victimizers of atrocities in Guanajuato at a rate that leads the nation, and impunity allows for the free movement of organized crimial groups and results in massive desertion by police officers, and the post-electoral panorama in the state “looks like it’s going to get worse, action needs to be taken now.”

This violence isn’t only rising but that is particularly “chilling” because of the horrors connected to it, according to an analysis shared by two researchers and a civil society organization specialized.

Not a week had passed following the electoral events when the fires were lit again in different parts of the state, from the Laja-Bajío region to León, from Moroleón to Valle de Santiago.

A series of massacres marked the weekend after the elections, by mid-week, Wednesday June 16th, an ex-mayor was killed on the highway between Apaseo el Alto and Tarimoro.

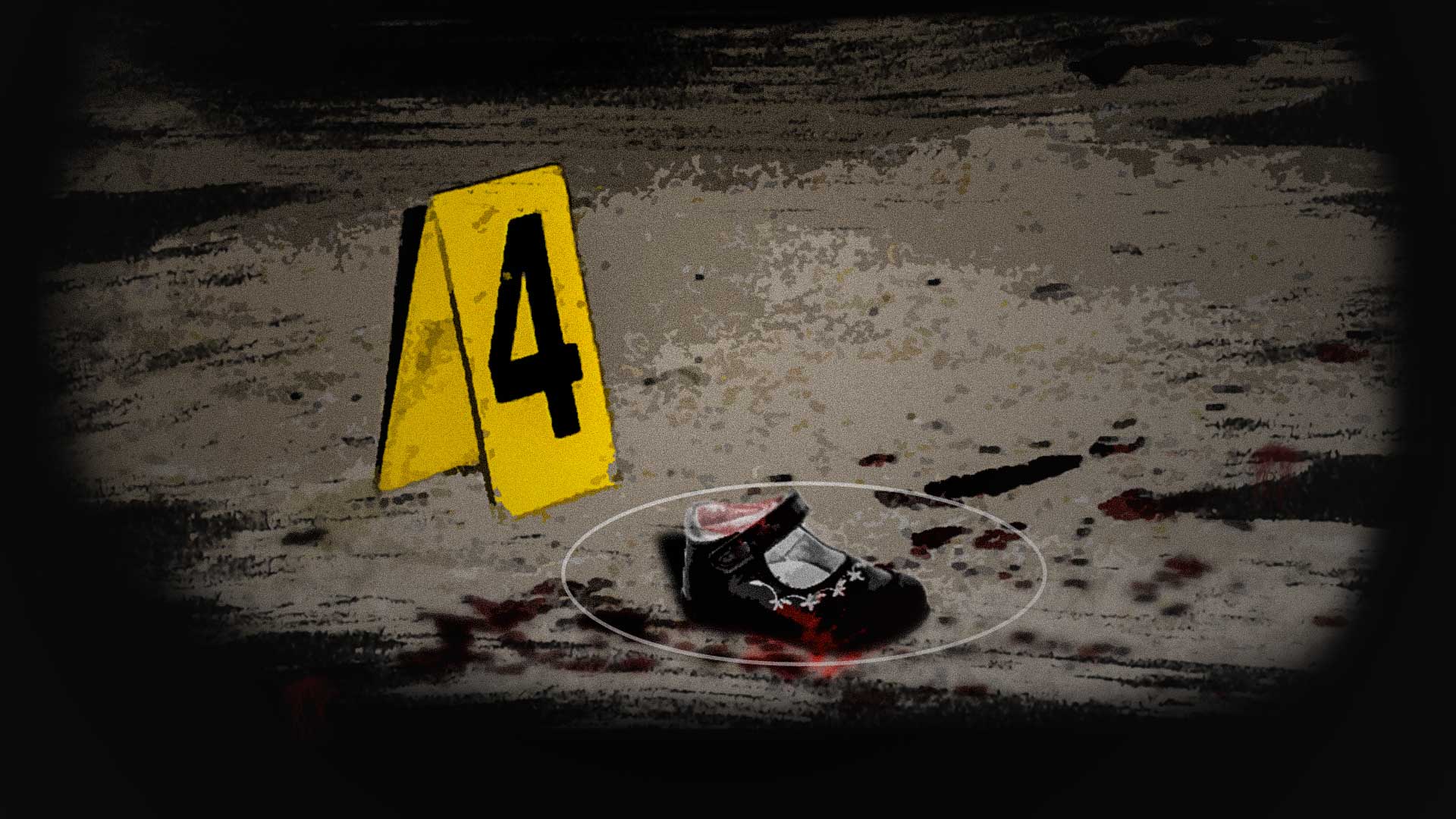

A five year old girl was killed in her home in Salvatierra. Four men at a party were shot to death in Celaya. Women from the same family received messages from men with their faces covered, who broke down their door with a sledgehammer in the small town of Pueblo Nuevo. A funeral procession went into mourning again as one of the mourners was attacked in Moroleón. Six lives were ended in a single day in León.

Over the weekend, the federal registry marked 33 homicides in Guanajuato. But on Wednesday another crime, this one political, was carried out, after an electoral pause marked by the assassination of Alma Rosa Barragán, the mayoral candidate for Movimiento Ciudadano in the municipality of Moroleón, who was shot to death two weeks before the elections.

The ex-mayor of Apaseo el Alto from 2009-2021, PRIista David Malagón, was the victim of a shooting while driving on Wednesday June 16th along the highway from Apaseo el Alto to Tarimoro; he died from at least six bullet wounds.

In their analysis, the experts concur that, as the violence has grown numerically and has filled national statistics with the worst crimes committed in Guanajuato, the kinds of violence committed is also reaching extreme levels of cruelty.

The organization Causa en Común presented their latest report on atrocities –crimes involving extreme violence– committed in Mexico over the first five months of the year, which they track according to press reports.

Guanajuato is in first place in various categories of the worst atrocities since 2020, when the organization began to publish these reports, which are meant to push back against official discourse in which “Mexico isn’t that violent anymore.”

One of the most worrying categories is the murder of children and adolescents, in which Guanajuato tops the list, with the highest recorded number in the country. Between January and May of this year, criminal groups have violently murdered 28 minors in the state.

“In Guanajuato there is a high level of violence, at the same time as there is a huge amount of impunity. The state has become an extremely risky location, even for security forces. To date no authorities have been able to or appear to have effective policies to stop this and to do the prevention necessary,” said Pilar Déziga, a researcher with Causa en Común.

Meanwhile, doctor Jéssica Vega Zayas, a research professor in the Social Sciences Division at the University of Guanajuato, speaks of unresolved violence that grows statistically “and therefore, is always qualitatively increasing.”

“To the extent that the criminality remains in impunity, the problem of violence grows. Among other factors is the battle between organized criminal groups. There is not a clear strategy to deal with this in Guanajuato, rather, these groups have been allowed to act autonomously and with absolute impunity.”

2021: five months of impunity, and counting

Causa en Común’s latest report, titled “Gallery of Horror: atrocities registered in media outlets,” recorded 2,712 events of extreme violence that could be classified as atrocities throughout México between January and May.

Guanajuato leads in four kinds of violence: cutting up or destruction of bodies (73 of 343 cases nationally); burning of bodies (29 of 248 total cases); massacres (37 out of 239 cases) and the killings of children and adolescents, with 28 of 213 victims.

Overall, the state with the most journalistic stories written about atrocities in the first five months of the year was Guanajuato, which was also the state with the most victims of atrocities (358).

Guanajuato is followed by Jalisco, Veracruz, Guerrero, Chihuahua and Sonora states with regards to these kinds of criminal violence. Over these five months, there was also an increase in reports of torture, the discovery of clandestine mass graves, and the killing of women with extreme cruelty.

“Given the federal government’s tendency to minimize the levels of violence, we did our first study on atrocities last year. We decided to make it known that the violence hasn’t lessened, not even close. Between 97 and 100 women and men are murdered in Mexico every day. But that number, which is high, doesn’t say much about the violence that is being lived through,” Pilar Déziga from Causa en Común told POPLab.

“They say there are no more massacres, there’s no more violence, and they show the number of homicides per day. That’s why we decided to carry out this study, so that we as citizens ask ourselves, and we can see how violent the country is,” she said.

They also thought it was important to differentiate the violence according to regions of the country. “It’s not the same when Indigenous people are killed in Chiapas or children and adolescents in Guanajuato. Guanajuato has the most of the latter, with 28 cases; in other states the situation is different.”

Pilar Déziga and Dr. Jessica Vega agree that, in addition to policies to prevent violence and combat crime and insecurity, there is a need for studies and analysis of violence on the part of government institutions, “not just police statistics on what is taking place.”

Deepening research into the kinds of realities and the problems facing states could create a basis for designing violence prevention programs.

Guanajuato, the Causa en Común researcher said “is where we see the worst problems, it was at the top of the list last year with the most victims of different types of violence. It’s evident that the violence hasn’t stopped and we haven’t seen an inflection point in the state that would indicate the numbers are falling.”

This situation reflects that fact that “there is a huge need for focussed prevention policies,” especially for children and adolescents, who are moving from being victims to becoming victimizers.

“[Guanajuato] is one of [the states in Mexico] with the most killings of children and adolescents. What is being done to reduce this violence? Often, they are being killed by other children and adolescents. We don’t track the victimizers, but when we go back over the findings we see an important number of children and adolescents committing crimes. This doesn’t have to keep happening,” said Déziga.

Another factor the researcher highlights is that the police and the public ministry in Guanajuato are overwhelmed, and that “there is not sufficient capacity to investigate or carry out legal processes.”

All of this has led to Guanajuato being “in a state of insecurity which is extremely fragile,” she said.

One of the things that caught the organization’s attention is that the spread of criminal organizations “isn’t being held back at all,” and there’s no response from the government on the politics of prevention, nor are the state police being strengthened. On the contrary, “it is number one in the killings of police officers.”

State, family and religion: incapable in the face of minors who are both victims and victimizers

Dr. Jéssica Vega, like Pilar Déziga, thinks the killings of minors, and their participation in violent events is the most disturbing and worrying aspect of the current reality in Guanajuato.

For example, Pilar notes that 28 minors were killed in Guanajuato between January and May, while in Jalisco and Baja California state, which tie for the second-most victims, there were 15 each. “It’s almost double.”

She thinks that “the step from victim to victimizer is very easy to make in Mexico, where there is no system to repair the damage to victims. There’s no investigations and no punishment, but also, there is no reparations to victims. There’s no budget at the Commission to Attend to Victims. It’s a vicious cycle.”

For the researcher from Causa en Común, the “Gallery of Horror” report only superficially examines “some of the super dark and pathological aspects that society should not ignore. We need to recover the ability to be moved and to stand up against these horrors. People aren’t just being murdered in Mexico, but a very high level of violence is inflicted.”

Social sciences professor Vega Zayas notes that the criminal groups who move with impunity through the territory of the state have affected and infiltrated entire families.

The competition between these groups, the increase in impunity and the lack of control on the part of authorities have also elevated the level of violence, which is now a tool for control by these groups are drugs, family structures and the competition for scarce resources, she said.

That would explain the dozens of attacks over the past years which have taken the lives of entire families in their own homes, in their own rooms, during a family gathering or a wake.

“This has to do with the notion that family is the most important thing in Guanajuato. There are people who join organized criminal groups at a very young age, in addition to that, Guanajuato has very low levels of schooling. When these youth join, they don’t understand the consequences of being involved in organized crime, nor do they realize that that choice impacts their entire family.”

She also says that, in a society like that of Guanajuato, which is marked by religious conservatism, “the idea is that the family will keep its kids in check, for the model of the family that is being defended,” because the idea was this was how the prestige of the family would be maintained.

Regardless, “to the extent that that was not enough, when neither the family nor the church can play the role of containing the youth, and once organized crime is in the mix, it can overwhelm the youth and it becomes an issue for the entire family.”

“What implications does this have in terms of attacks on families?”

“One of the common elements today among organized crime groups is that it is well known that their mothers are a vulnerability for these youths. That’s why they end up killing the mothers, because they know that from that point on, the youth will become desolate.”

Another factor of control or recruitment of youth on the part of the criminal groups is the use of drugs, especially crystal meth, which is highly addictive.

Dr. Vega gives an example of this in the city of León.

“León has a history of leatherworking. We noticed the youth were using a solvent known as “agua de celaste,” which is readily available. The problem is that they acquire it very easily and they inhale it, this is very common among youth who have addiction issues.”

This behaviour changed when criminal groups arrived in full force.

“There are very old gangs in León, which is part of a long tradition; the youth joined these groups not necessarily to participate in criminal activity; but rather to belong or because they identify with the most popular neighbourhoods in the city. But as criminal groups entered, the drugs that were used changed, and so did addictions, crystal meth arrived and began causing very strong addictions at a very early age.”

She adds that alongside the increase in addictions among girls and adolescents are teenage pregnancies and low schooling levels, which are characteristic of a “very conservative society,” because of which these youth face a situation of enormous vulnerability.

Meanwhile, according to the university researcher, in Guanajuato there is a struggle between two cartels (Santa Rosa de Lima and Jalisco Nueva Generación), as well as other groups, including La Unión in León and remnants of the Familia Michoacana and the Templarios.

The effects of this include high rates of disappearance, political killings during elections, such as of the mayoral candidate in Moroleón, and killings like that of Javier Barajas, an activist and official with the State Commission for Searching for the Disappeared and brother of Lupita, a teacher who was disappeared and her body found in a clandestine mass grave in Salvatierra.

“This sends a very bad message, a very worrying message. The people who are the most vulnerable of all are completely alone in dealing with this situation. We need these groups to be able to count on government support, because they are the ones facing down in the most obvious way the repercussions of organized crime, they can’t be left alone and exposed to this level of aggression from organized crime.”

The academic insists that special attention be paid to search groups. “They are the most vulnerable. What hope is there for the people who are exposed and realize it, if they start being killed.”

The failures are many.

“If we don’t have long term strategies, which go beyond the government’s terms, we won’t be successful” in preventing and stopping the violence. “In Guanajuato, we have had a National Action Party (PAN) government for a long time, but there are no alliances with the federal government.”

On the other hand, organized crime goes beyond Guanajuato. “It’s part of what is happening in Jalisco, Michoacán, México State, these are regional, interstate conflicts, organized criminal groups go beyond states, their goal is territorial occupation. The same goes for the federal government.”

“What are your expectations with the incoming governments and the possible infiltration of crime groups?”

“These groups have already started pressuring to define who governs or not in particular territories through support or at the very least, through an absence of threats. It’s an analysis that we have to start doing. Those who live in the territories controlled by crime know that there are no resources to confront them, and if they wanted to confront them they know that their life would be at risk, as well as the lives of their loved ones. We know that, if they aren’t allies, they got the message to not mess with them.”

Victoria Espinosa is a feminist journalist. She has been the correspondent of weekly magazine Proceso in the Bajío region since 1997. She is a member of the National Network of Women Journalists and the Collective for Free Expression in Guanajuato.

This report was originally published by POPLAB, which is part of the Media Alliance organized by Periodistas de a Pie. You can read the original here.

Click here to join Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona