Damián Genovez Tercero is home. A year and a half after he left his home in Chiapas searching for a better life in the north of the country, and 11 months after being killed by the soldiers he admired, his body was carried 2,000 kilometers along the most dangerous route in the country in order to return to his family and friends. This is his story.

Text: Daniela Pastrana, originally published June 28, 2021.

Photos: Isabel Briseño

Translation: Dawn Marie Paley

TAPACHULA, CHIAPAS– This is, above all else, a story of poverty and abandonment. It’s the story of a young man who set off to seek a better life than what this lush place, which is ripe with life and exotic fruit could offer. Here, 12 hours working in the fields pays US$5 a day.

The young man, who was 18 years old, wanted to leave the misery behind, but we went straight into the wolf’s mouth, up there where everyone blesses us, where appeals to God are everywhere, even in internet passwords. There, more than 2,000km from his home, he was kidnapped by criminals. Then he was killed by soldiers in the Mexican Army; he had once dreamed of being just like them. Through all of this he was with his younger brother Alejandro, who was disappeared and remains missing…

A year and a half after he left to go north, Damián Genovez Tercero, the güerito (light skinned man) who wrote songs between the corn stalks in the fields, returned home in a coffin.

In order to get him home, his parents had to undergo rains and hunger in the Zócalo in México City. They fell ill and had to deal with the torturous bureaucracy and the disregard of a government that has promised to protect the most vulnerable, but who cannot recognize when its soldiers have done wrong.

Damián’s body was exhumed on Wednesday June 23rd from Municipal Cemetery #2 in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, and rolled as if in a cocoon of plastic. It traveled along the most dangerous roads in the country, together with his sick father, two federal bureaucrats who left as soon as they possibly could, two funeral home employees who counted every hour that passed traveling in pesos, two lawyers and two journalists.

Finally, on Thursday the 24th, he arrived home. He was buried on a muddy, rainy afternoon, amid flies, yelling and wails of mourning from unmasked faces. Because in the home in which he was born, there are older and bigger problems than a pandemic.

Tamaulipas, June 23, 9am

In Nuevo Laredo’s Municipal Graveyard #2 there are around 15,000 graves. The person in charge is Donanciano Blanco, who explained to us that most of the burials are for heart attacks, kidney disease and diabetes, and that on average there’s about 12 burials a week, though recently, for some reason, that number has dropped. Last week there were only three. Covid hit hard, he himself has two family members who died, of a total of 747 in the city, but they don’t come here because they are cremated. There is also another public cemetery and two private ones. What about violent deaths? They happen, yes. But not as often as those who die of illness, he said.

In the case of Damián Genovez a “premature exhumation” was carried out after less than a year. It is most common that bodies are exhumed after more than seven years in the common grave. A premature exhumation is a little more complicated, because the body is still intact. That’s why he asked RB (a worker at the graveyard who asked to remain anonymous) to help him out.

“He’s got something in his nose, he doesn’t smell, because the other guy threw up right there,” said the head of the graveyard as we waited for everyone who was supposed to arrive: investigators from the State Attorney General’s office, staff from the Executive Commission for Attention to Victims (CEAV), and from the State Commission Against Health Risks (COFEPRIS), as well as Raúl Tercero Arriola, Damián’s father.

The father’s tragic journey has been a long one. For the last week, since the agreement to exhume the body was signed, his problems haven’t stopped. That day he went to the hospital for kidney stones that required an operation. He was in the hospital for two days, when he got out he took a bus to Tapachula with his wife and uncle. “The doctor said I needed an operation, but I told him: ‘I can’t, I have to retrieve my son.’ So I signed a form saying I was leaving.”

Once Tercero arrived in Tapachula he waited for the CEAV to make good on their agreement to take care of his travel costs. He told us over the phone that he didn’t know whether he would travel to Nuevo Laredo on Monday or Tuesday. By noon on Tuesday, he still didn’t know. He had to borrow money to fly to México City and from there to Monterrey, where he ended up getting stuck, because there was no space on the buses leaving for Nuevo Laredo until five in the morning.

So it was that he arrived at the exhumation just after 9 in the morning, without having slept and with 10 pesos in his wallet. Two bulletproofed National Guard trucks were already there waiting for him. The investigators had not arrived yet but Donaciano Blanco said the authorization had already been approved and they didn’t need them.

As we walked toward the grave, the bureaucrat working for the CEAV told us that he drove from Mexico City to Nuevo Laredo the day before, and tried to convince us to stop and sleep in a hotel on the way to Tapachula. Beyond the macabre idea of sleeping in a hotel with an exhumed body in the room next door, his proposal fell flat: the funeral home is in a rush, and their time is expensive.

The Vélez Funeral home, based in Nuevo León, is the same that charged Raúl Tercero every day and every night that they were in custody of his son, to a total of nearly 200,000 pesos (around US$10,000). Tercero paid to the best of his abilities, taking on more debt to do so. According to his lawyers, Tercero has spent nearly 600,000 pesos since July 2020, when soldiers killed Damián in a military operation. That has been the price this man, a truck driver, has paid as he searched for his son and set up camp for nearly five months in front of Mexico’s national palace.

“Not once in my life have I seen that much money at one time,” said Raúl Tercero.

In Damián’s grave another skull appears, of a body they moved to get to the young man’s corpse. A common procedure, according to the gravedigger.

The father cries when his son’s coffin appears in the grave. The psychologist from the Holistic Attention Center of the CEAV asks him if he wants to be in the next part of the exhumation. Raúl Tercero says yes, and complains that he didn’t get the money to be present. “We always have to be responding to things [from Mexico City],” says the psychologist, frustrated. She traveled from Monterrey together with the legal representative of the Center for Attention to Children (CAI).

The next step is difficult to narrate: in an area near the common grave, the funeral home employees take Damián’s body out of the scuffed up coffin, they put it on three gasoline containers, cover it with salt, and begin to wrap it first with packing tape and then with cling wrap.

The image is disturbing and desolate: in front of us, the embalming shows the rawness of the ruined life of a young man.

But nothing prepared us for what came next. Raúl Tercero wants to put “the bit of clothes” he got back from the Attorney General’s office into the new coffin. Each piece is individually wrapped. But the pent up emotion makes his hands shake and he can’t open the bags. No one approaches him as he sobs harder and harder and talks to the plastic wrapping.

Before we left, while the funeral home workers changed vehicles, Raúl Tercero went to his place in the Hipódromo neighborhood, the last neighbourhood in which he lived in Nuevo Laredo. It’s a single room. During the five months he was away the house was ruined by abandonment and the rats ate the plastic bags. The last thing he brought out to the truck was wrapped in a blanket.

The man packed up quickly. He shows us each thing he bought so that his children would be comfortable in the city, to which his wife Evelyn never wanted to return. In the room, there’s broken dreams and photos of his two absent sons.

Tamaulipas, June 23, 2pm

Before we pull out, Raúl Tercero warns us there will be few stops. The funeral home wants to make it to Tapachula in 24 hours.

The armoured trucks of the National Guard which were with us in the cemetery are replaced by a single patrol car. At the last minute, the representatives from the CAI advised us that they are not authorized to travel with journalists in the CEAV vehicle, as was originally planned. We decided to travel in the truck with the lawyers, who offered so long as Pie de Página paid the travel costs.

We left nuevo Laredo in four vehicles: the National Guard car, the funeral home truck, the CEAV’s vehicle with Raúl Tercero and the lawyer’s truck, which we’re in. In the following hours, two things become clear to us: the funeral home is in charge (they decide the route and are the only ones the National Guard cares about) and they are in a huge hurry. They won’t slow down. They even leave the CEAV vehicle carrying the father who worked so hard to get to Nuevo Laredo behind.

We traversed Nuevo León and Tamaulipas. After midnight, we entered Veracruz, at Tampico. Raúl Tercero knows these roads well and is upset by the route we’re taking. It’s the shortest, but it’s also the most dangerous.

His suspicions are confirmed just after four in the morning. After we pass Nautla, the National Guard doesn’t want to continue. They tell Tercero that this part of the road is dangerous, and they’ve been shot here before. Our escorts leave us for 90 minutes in the stretch of road where we need them most: a dark highway that’s full of potholes, where the CEAV vehicle ends up bending a rim and popping their tire. The good thing is, there’s a full moon.

At six am we stop at a gas station to wait for another car from the National Guard, or at a minimum, until sunrise. Raúl Tercero told us how hard it is to be a truck driver, and a new reportage on the exploitation of workers comes into the horizon. He takes out a square bag from his backpack, like a lunch box, filled with pain medicine. “When I get it really bad I have to inject myself. I do it myself. I’m used to it,” he said.

Tapachula, Chiapas, June 24, 6pm

Twenty eight hours after leaving Nuevo Laredo we arrived in Tapachula. I can’t stop thinking about how we traveled more than 2,000km in the opposite direction as thousands of migrants. And how, if we’re tired, at least we’re not shut into the back of a truck. It’s raining in Tapachula, the insistent rain that characterizes the region. Two hours ago, Evelyn, Raúl Tercero’s wife, called to ask where we were, because the whole family was waiting. And there, in a small covered area outside of the house in the Álvaro Obregón ejido, his grandmother Gloria; Silvia, his biological mother, and Evelyn, who raised him. His sisters. His cousins. The sobbing as the güerito returns couldn’t be more heartbreaking.

The family walked to the cemetery in their neighborhood, dodging rain and mud. Outside, at some point, the National Guard and the funeral home workers left without saying goodbye. Only the representatives of the CEAV make it to the cemetery, withdrawing quietly when they see the representatives of the CAI in Tapachula arrive. They’re the only representatives from the government at Damián’s funeral.

It’s a strange sensation. A few hours ago, in another cemetery, Raúl Tercero was surrounded by bureaucrats he didn’t know, his mask holding back his sobs while he watched strangers remove his son’s body from the earth. Here, it’s just his family, the only ones with masks on are the CAI workers, and Raúl Tercero lowers his son’s body into the earth with his own hands.

The sobbing is disorienting. The ropes used to lower the coffin get tangled during a few difficult moments. One of Damián’s sisters is in a bad way. His grandmother too.It’s incredible to imagine this scene in this leafy place, so green, where you can pick fruit up off the ground. Here there are pineapple mangos that taste like pineapple and banana mangos that taste like bananas, huge lichis they call rambutanes and guayas, which are like sweet miniature lemons, which taste like a mixture of wild black cherry and plums.

“My grandsons left because here, even though we have all of this, there was nothing for them,” said Gloria, the grandmother.

“They left happy for a new life. We went to see them off at the Corona and they were on their way to travel and work. We never imagined that this would happen… If there was work they would never have left our neighborhood. There’s everything here, fruit, everything, except a stable job… If there was, say, a factory or something where the youth could go and work, they wouldn’t leave, but there’s nothing here, that’s why this happened, because they left to make another life.”

The women thank us for having accompanied the journey of their son and grandson. If this was a rich family, I feel like there would be live coverage by many journalists, with sat phones.

But there is no other media here. This is, above all else, a story of poverty and abandonment.

Everyone’s sons

Damián Genovez Tercero and Alejandro Tercero Meza weren’t brothers, they were cousins. When Damián’s father died, almost 10 years ago, his mother Silvia left him in the care of his brother Raúl. She was sick and thought she was going to die. “Look after him as if he was your son,” she said.

“Of course I will,” he replied. “It’s as if I asked you to care for my son.”

Raúl Tercero and Evelyn Meza had four children, two boys and two girls, and they adopted Damián as their own. Evelyn tells about how she left her son Alejandro with her mother in law when she had to go to work.

“Here we all look after each other. Her sons are like my sons and my sons are like her sons,” said Evelyn.

Grandmother Gloria has three great grandchildren and seven grandchildren. “I had nine,” she said. “I’m so sad because I used to give them something to eat when their mother went to work selling. I raised them together.”

We talked about absences. Of how important it has been for the whole family that Damián made it home and be buried alongside his father and his grandfather.“Even if it’s just his body, having him here, where I can go see him, talk to him, because I feel like he’s not gone, licenciada. I love my grandchildren dearly.”

After the burial, the family invited us to eat with them. The women organized the meal while the children played around with the camera.

Gloria thinks Damián’s admiration of soldiers and his interest in entering the National Guard came from his grandfather, Antonio Tercero, who was a police officer for many years. “My husband couldn’t read, but he wasn’t stupid. He worked in the milpa (subsistence agriculture), but he would say ‘this isn’t going to work for us.’ That’s why he went into public security,” she said.

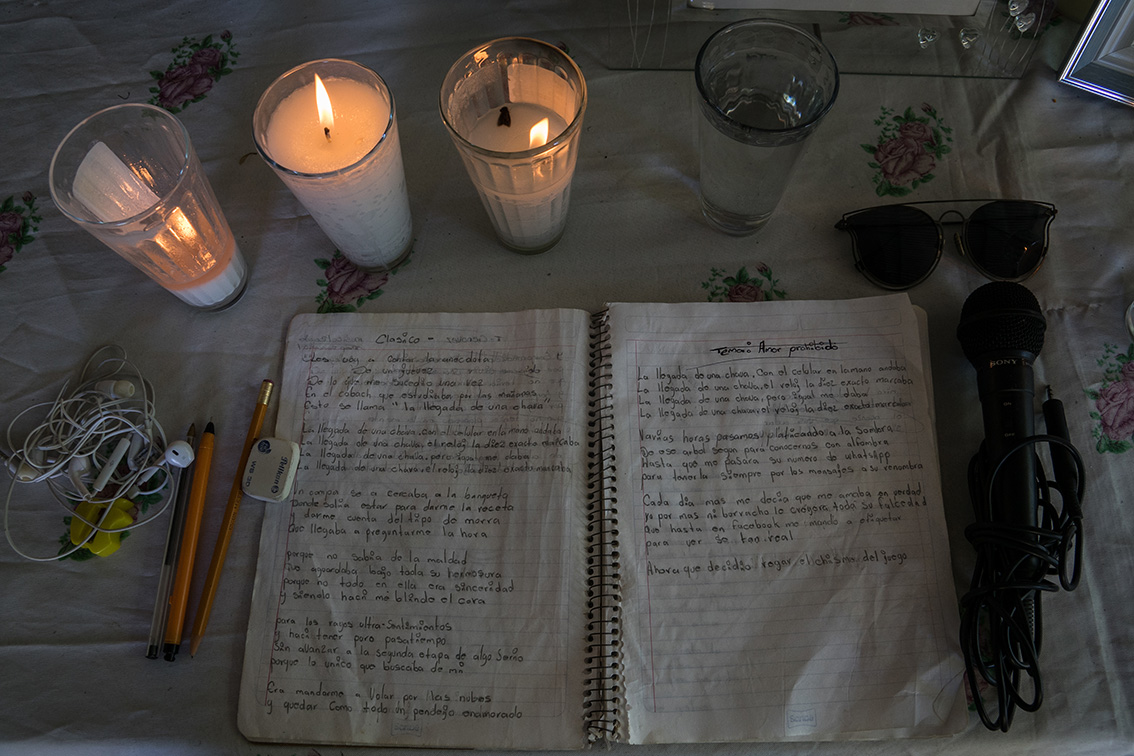

Silvia, Damián’s mother, said he never got into trouble. “He would write and write, he always had his notebook and his pencil,” she said, sadly.

Damián wrote songs. His mother showed us his notebooks, which she put on an altar together with his microphone, his headphones and his pencils. There, in the hand of a youth, are the letters of dozens of songs. Almost all of them are about falling in and out of love.

Por esta aventura de este amor prohibido / Que me mandó cupido un viernes inesperado / Con el amor que me brinda / Pude curar las fracturas de una vieja pasión

For this adventure of forbidden love / Which cupid sent me on a random Friday / With this love that gives me / I could heal the fractures of an old passion

Esta escrito, ya está en la libreta / De puras historias. Pobre el vato quiso ponerse / De enamorado con la morra que conocí / Ella misma me dijo que conmigo quería pecar

It’s written, it’s in the notebook / Of pure stories. The poor guy / Who falls in love with the woman I met / she herself told me she wanted sin with me

Alejandro is still missing…

“How do you feel, Don Raúl?”

“I feel calmer, because my boy is here now.”

He repeated what he had already said a few times on the way: “I took him here and I had to bring him back.”

We left the family and promised to stay in touch about the advances of the investigation about Alejandro, his younger son, who is still disappeared. The authorities offered to hold meetings on the 30th of every month. Thinking of it brings a shadow across Raúl Tercero’s face, as he tells us how, in a few days, he will go back to Nuevo Laredo to return the keys and the phone to the company where he worked, which already took him off payroll.

“Now, my job will be to keep looking for my other son. I need him back, in whatever form, but I need him back. Even if his life is left there, I won’t stop until he is back home.”

Daniela Pastrana wanted to be an explorer and see the world, but instead she became a journalist and decided to try and understand human societies. For six years she ran the Red de Periodistas de a Pie. She founded Pie de Página, a digital outlet that seeks to change the narrative of terror that is installed in the Mexican media. She always has more questions than answers.

Isabel Briceño has never liked the fact that happy stories come to an end, which is why she captures them on camera, she captures sad stories in a search for answers.

Click here to join Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona