Anthropologist Raquel Padilla once said that the drug known as crystal meth was destroying Yaqui youth. “And if the youth are destroyed, what is left?” she asked. How can this new extermination be stopped?

Text and photos: Daliri Oropeza, originally published May 15, 2021.

Translation: Pie de Página in English.

PÓTAM, SONORA–Alely picks up her violin, the one she keeps in a special place in her room. She keeps it in its case, besider her traditional clothing, woven with red flowers. She hangs the case from her shoulder, and starts to run with her face mask on. She runs across the earth that rises up in the streets of Pótam, one of eight Yaqui villages. She goes to the bus stop heading to Vicam Station, where she’ll take her music class with a well known teacher named Koko.

She learned to play the violin when she was seven years old, now she’s 18. First, she had a miniature violin. She learned by listening. This is how she has come into contact with her own Yaqui tradition. Together with other youth, she’s part of a generation of Yaqui women who play the violin, to which the Pascolas and Matachines (traditional dancers) dance.

This ceremonial responsibility has largely fallen to men, especially after the persecution of women during the Yaqui War. Traditional music and dance, as well as other duties, fell to men, as the women had to be protected.

Alely recognizes that Yaqui traditions are being lost among the young. She says that among many people her age, in addition to discrimination and urbanization, there is a lack of interest, a failure to speak the language, and the consumption of narcotics.

She talks about how it became more common to learn of murders. According to official statistics, in January of 2021, the municipality of Cajeme, Sonora, recorded 54 homicides; which compares to 28 in the same month last year. Cajeme, Guaymas and Empalme are among the 10 most dangerous municipalities in Sonora state, according to an analysis of the state Security Secretariat.

According to the records of the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System, Cajeme is, month after month, one of the 15 municipalities with the highest number of homicides in México.

Data from the 2017 National Survey on the Consumption of Drugs, Alcohol and Tobacco showed that children as young as 12 were regularly using controlled substances. In 2019, Sonora’s Health Secretariat documented, of 7,331 people cases of people with addictions to substances, 72% were for the use of methamphetamine, also known as crystal meth.

In an interview she gave before she was murdered by her partner, the anthropologist and ethnohistorian Raquel Padilla Ramos warned of the dangers of addiction in Yaqui territory.

“Crystal is destroying young Yaqui people, and if you destroy the youth, what is left? … I’m very worried about that. I wish it wasn’t like that, but I don’t have clarity on how it can be prevented. I know that they need to have better opportunities in life, and strengthen their relationship with the land, which has been lost, because now they rent their lands because they don’t have the means to make them productive, and in losing that relationship with the land, they lose a lot of their culture.”

Epicenters of Yaqui culture

Alely rests below the shade of a giant tree. It is a poplar which gives enough cool shade for her to rehearse. She’s gotten out of practice during the pandemic. These days, she goes to Vícam for classes sporadically. Before, she went every week.

She misses concerts and performing at events in her town. Covid slowed the rhythm of the eight Yaqui villages. There’s no classes, and many lost work.

The health centers don’t have enough equipment to attend to the sick, which is why most have had to go to Ciudad Obregón or Guaymas to seek medical attention. Those who didn’t lose their jobs go to work in maquilas in Empalme or to work on the farms. There, youth also drink in the street.

“They should do the dance of the deer to distract themselves, learn about things that are meaningful to them,” said the young violinist, about the Yaqui youth who today use drugs or commit crimes.

In music, Alely found a life project. Thanks to music, she shares traditional Yaqui songs, and meets other youth who are interested in their culture, she also learns and plays folk songs that have become popular, like La Yaquesita or Flor de Capomo, which were written by José Molina, who is from her same town.

Most Yaqui songs are unknown. They have to be accompanied with dance. The music isn’t composed on its own. There are recordings of songs from people in each of the eight villages; they are played on the recently founded radio station Namakasia Radio, the first Yaquí community radio.

Autonomous education and independent efforts

Namakasia Radio was born out of an agreement taken by the assembly of the traditional guard in the Yaqui town of Vícam Estación. It was founded in alliance with a prior project, in the same town, called Sewa Tomteme, a cultural center for music, dance, and languages like English or Jiak Noki (the Yaqui language).

Here, professor Francisco Ramírez, who is better known as Koko, shares his collection of music and his musical knowledge. He is a mathematician who trained as a writer, and he’s spent his last years sharing the knowledge of his people.

In addition to being part of Sewa Tomteme, he founded the group of which Alely is part, called Jiak bwia-Tierra Yaqui. The group has gone on international tours, performing Yaqui music and dance.

When Alely was studying in college, she still took Yiaki o Yiak Noki language lessons. Now she works on water purification, because of that she’s put learning her own language on hold. Her grandmother spoke it, but her mother and her aunts and uncles didn’t.

She’d like to go to veterinary school. With that idea in mind, she’s aware that she’s doing really important work regarding the lack of water in her town. In Yaqui territory there is a generalized drought and the water stopped running in the river. Now it’s dry. Most say that’s because of the imposition of the Independence Aqueduct. Six years ago, you could still watch the river flowing.

In an extensive study of the Independence Aqueduct, Raquel Padilla warned that the aqueduct would damage Yaqui culture, organization and their historic territory. She noted that the damage to their territory and culture caused by the major hydraulic project would be irreparable.

The young Yaqui woman manages to make it onto the red bus, which is a little dilapidated, and passes once an hour. It will take her to her teacher Koko, and with her colleagues of the musical group Jiak Bwia-Tierra Yaqui. Once she’s on the bus she runs into her language teacher, Domitilia, who runs the Pótam Cultural Center. She sits beside her.

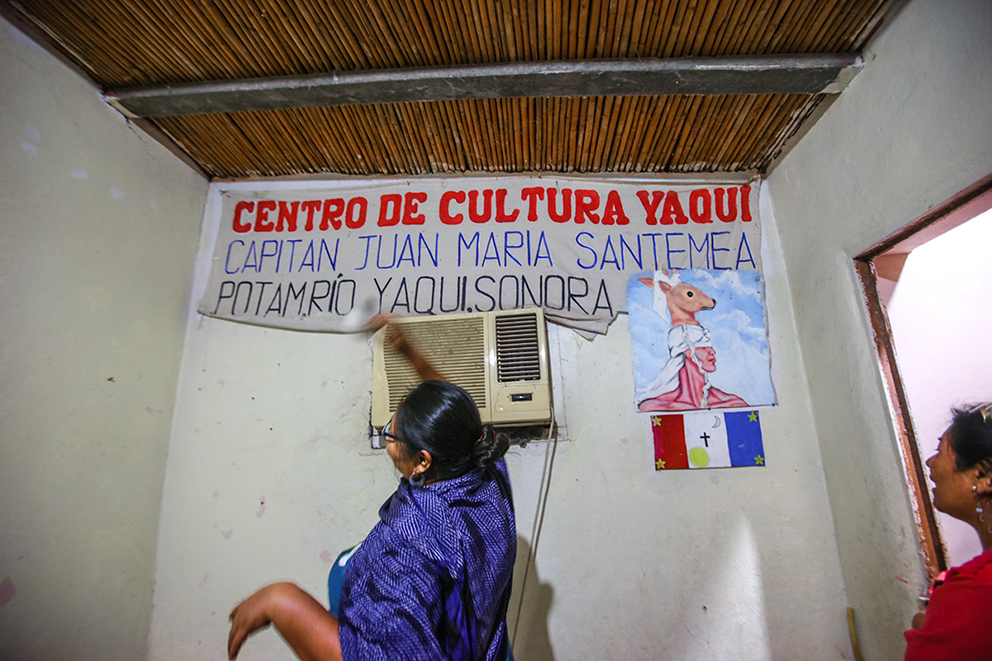

There are five cultural centers in the eight Yaqui villages. Most don’t have any funding and depend on donations from locals to operate. The one in Pótam is called “Capitán Juan Manuel Santemea,” in honor of the man who, after the war, the return and the deportation, came back to found the town of Pótam.

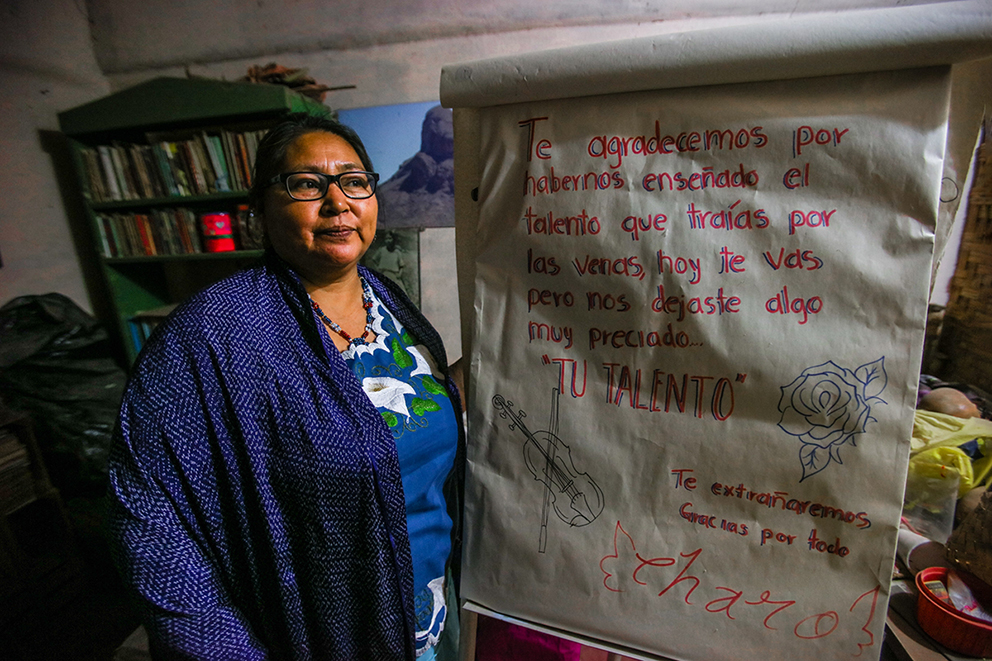

Domitila, the teacher, is one of the cultural referents in the village of Pótam. She expresses what she sees among the Yaqui youth:

“The problem is the synthetic drugs. God knows what they are made of. That’s why there’s less tradicional ceremonial groups, like the Cuarejma. Why? Because they’re lost in their own world. There’s people who haven’t come back, who took drugs or who robbed, or assaulted someone, and they’re gone,” said Domi.

Her concern is that there are no public policies to assist and protect Yaqui children, adolescents, and youth. There’s no universities. There’s no support centers for people with addictions. The cultural centers have no resources.

Among the activities that carried on during the pandemic include work to create a Justice Plan for the Yaqui people, which was ordered by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and began under the supervision of the head of the National Institute of Indigenous People, Adelfo Regino Montes. They have already begun distributing resources connected to the plan to various productive sectors and in housing. The improvements in education, health or culture are less visible.

Namakasia: don’t break

The folks that participate in Namakasia Radio like talking about history and speaking in Jiak Noki. Mario Luna is the founding host, together with professor Koko of the station, which transmits at 87.7fm. He said that the transmitter burned out, probably because of the high May temperatures, which seem higher because the river is dried up. Meanwhile, they’re transmitting online, as they did when they started three years ago.

The radio station’s slogan is “supporting the dignified Yaqui struggle.” Among their shows are various independent efforts, they also play music people have sent in. Now, with the transmitter dead, people are demanding the station come back, since they listen to it while working the fields or eating with their family. It is the only place where some of the songs of Pascola or Venado are played, no other station transmits them.

That, for the founders of the station, is a sign of success, since the programs have meant that Yaqui family traditions are taken up again, accompanied by music and radio. Nakamasia, in the Jiak Noki language, means “stay firm, don’t break, or hard,” according to Luna.

They have made an effort to have children involved in radio station’s activities. They have a radio program called Usiim Noki, the radio program of the children of the Yaqui tribe. For Luna, it is important to promote intergenerational dialogues in the eight towns that the radio waves make it to.

“It’s important to share in our language, because for the people it is important for them to hear their own language on the radio or online,” said Luna.

The goal of the radio, and much more broadly, is to strengthen communication within the Yaqui tribe. “Formally launching Namakasia Radio is part of our communication strategy together with the Traditional Guard, where the language and culture of the Yaqui Tribe are promoted as is information and communiques about the truth of our reality, which is different to how the predatory media have lied and minimized the courage of the Yaqui Tribe.”

During the pandemic and vaccinations against Covid 19, Namakasia radio has played a fundamental role in informing the elderly about the safety of vaccinations, because of their work more grandparents went to get vaccinated.

“Here the kids come to experiment, they can play and say what they want, unlike at other stations. What is important to us is how they agree to talk. That they listen to those who speak our languages, and those who don’t speak can listen. We’re still in a phase of testing and training,” said Luna.

The radio has transmitted softball games, organized by an independent league with women’s teams in the eight towns. The team from Loma de Bácum spoke with Pie de Página. The team’s back catcher said that because of these sporting events, less youth are involved in criminal activity.

Women and deportation

Alely managed to make it to her rehearsal during the pandemic. She is the descendent of a family that was exiled and enslaved in Yuacatán. That’s what happened when Porfirio Díaz imposed his train project at the beginning of the Twentieth Century, at the cost of many Yaqui lives. The great-grandmother of the young musician –who knows little about the history of this war– was able to return to Sonora after working in henequen plantations in Yucatán.

The army went after women specifically during the part of the Yaqui War when Porfirio Díaz ordered the detention and the deportation of Yaquí people in transit.

Those who today live out their lives in Yaqui towns can see that there is an ongoing process by which women, and especially young women, are taking back spaces and activities they abandoned during the war, like holding political office, and holding traditional authority.

When she plays her music in the shade of the poplars and the mezquites, near a pool of water, Alely keeps these memories of her family alive, her peoples’ lived experiences of resistance and struggle. Even if she doesn’t know it. As long as she plays the violin, they’ll stay alive. She is honoring the tradition of struggle in which her ancestors lived.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona