Two reporters in Tapachula, Chiapas, look at how migration has shaped—and continues to shape—the border city.

Text by Ángeles Mariscal y Silvana Salazar, originally published in Chiapas Paralelo, March 31, 2022.

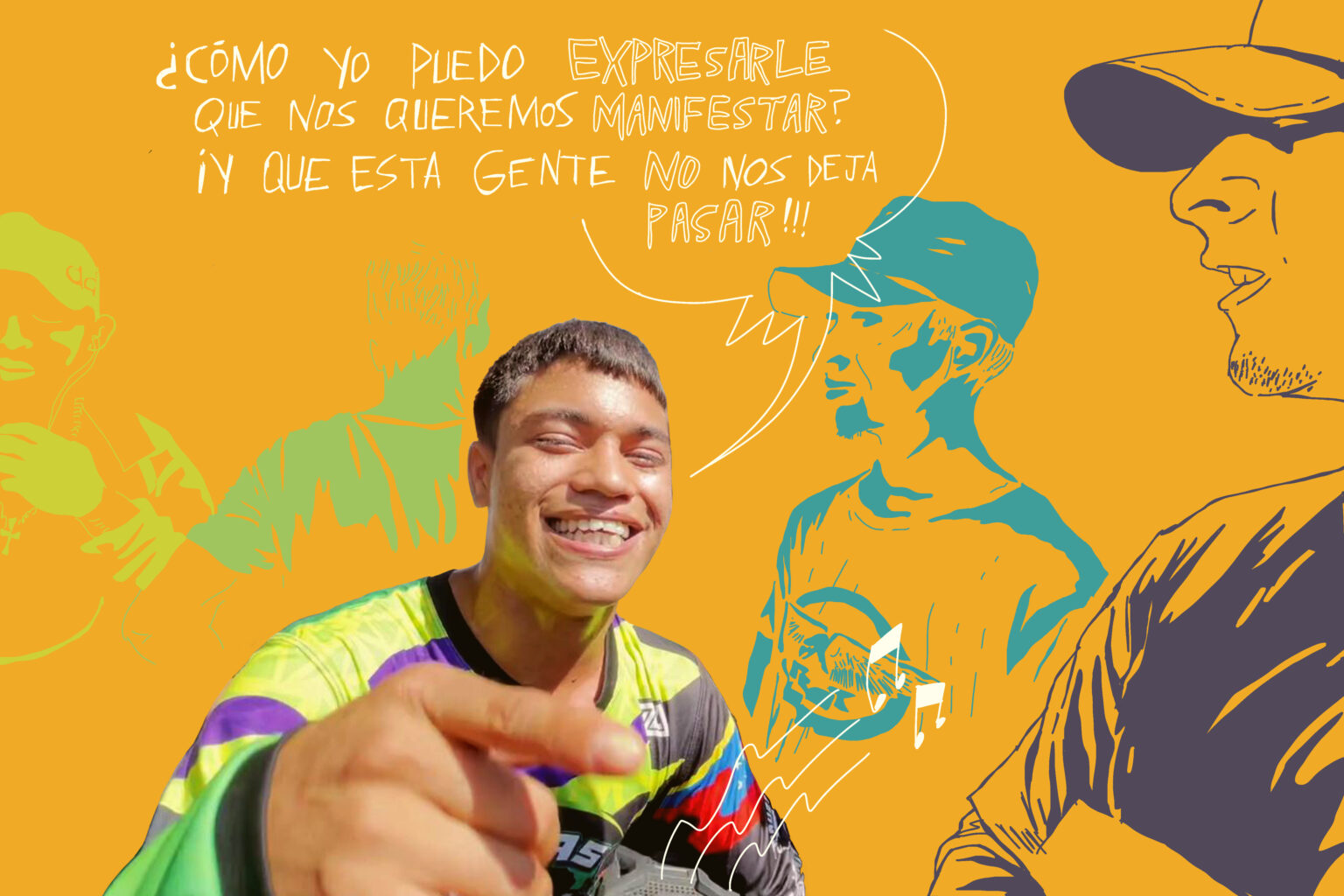

Illustrations by @ConejoMuerto.

Translation by Pie de Página in English.

From the mountains of Lebanon, to the war in Europe, to dreams that began in Asia. It’s been over a century since people from all over the world began to arrive in the land of the Soconusco, and started to build, together with the people from this land, the most prosperous economy in Chiapas, on México’s south border. This economy is structured by coffee plantations, international cuisine and in the multiple knowledges and abilities that come together in this cosmopolitan region.

In the Soconusco region there is a city that is considered to be its pearl, the most desirable place, which is Tapachula. Its residents have a goal: to recover their historical memory and recognize their migrant heritage, and in that way, imagine and give form to a new identity that is the product of the ongoing migration that’s here to stay, be it for a while or for the long haul.

Giant trees over 30 meters high, free flowing rivers, flowers, palms, pre-historic ferns, humid air, and fertile land where any seed that falls to the earth will grow into a plant. This region became famous when Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, before he wrote Don Quixote, wrote to King Carlos V that he should grant him the governorship of the province of Soconuso, which in that era was part of the Capitancy of Guatemala.

In the historic volume Chiapas in the eyes of foreigners: XVI and XXI Centuries, José N. Iturriaga recovered the letter where Saavedra made his request to the king. “I ask in the mildest way that H.R.H. decide to send me to an office of Indians among the three or four that are currently vacant, in the Kingdom of Grenada, or the governorship of the Soconusco province in Guatemala, or an accountant of the galleries of Cartagena, or Corregistries in the city of La Paz, whichever of these careers H.R.H. wishes,” according to the document.

The king didn’t grant Saavedra’s wish, but the reputation of the region travelled to the ears of those who, for various reasons, decided this was where they wanted to live.

Migration and adventure don’t always start out with a happy story. Such was the case of the grandmother of Yamel Atihé Guerra, a psychologist from Tapacula who is the granddaughter of Lebanese migrants who left their country because of hunger and war.

“My grandfather came from the mountains of Lebanon. Unfortunately, he lived through a very difficult era of starvation, and that is why, in the end, he decided to make a new life in America. They came fleeing hunger, and the war that was being conducted by the Ottoman Empire.

“My grandfather told us once how they watched one of their sisters die of hunger and, he said ‘you can’t eat money, and there was no food, and I couldn’t give money to my sister to eat.’”

For Yamel it’s clear: in her family and in those of her neighbors, there are shared histories that connect various generations who were born in the region. “They all had an experience of suffering, of injustice, of anger and also a common desire that aspires to happiness, to be able to provide well being for yourself, and for your family. It’s the common denominator among everyone who struggles in this life, in this case a migrant, from any country, during any time period. I understand that people don’t just leave their countries for no reason,” she said.

Atihé’s family home is located in the central area of Tapachula, in which grows is a giant tree filled with birds, iguanas and flowering plants, a tree that gives shade and coolness that help cope with the humidity and heat of this chosen land.

This tree could even be the symbol of the spirit of what is lived inside of homes. “When grandfather José Athié Athié came to Tapachula in 1920… Tapachula was multicultural, his neighbors were Japanese, in Henkle House there were Germans, there were people from France. There were people speaking all different languages, telling different stories of migration and adventure,” she said.

Just like the Atihé family, other Lebanese people arrived to the region, and with their entrepreneurial spirit they founded marvelous fabric stores, and a style of doing business that, a century later, allows thousands of people to acquire goods: a system of monthly payments for purchases; that was part of their legacy in this region.

Among the first massive migrations to Tapachula and the Soconusco region were Germans, who first tried to settle in Guatemala and later here, where they established large coffee plantations.

Thomas Edelmann, who was born in Tapachula and whose ancestors are German, is one of the most important coffee producers in the Soconusco region. “I’m the fourth generation born in Tapachula, he said, and his physical appearance rules out any doubt.

The arrival of his ancestors wasn’t easy. “My grandparents talked about the war that made them leave their country, they’d say, ‘you don’t know what it’s like to go hungry at any given moment.’”

Later, migrants from China and Japan began to arrive. They were attracted by promises of prosperity by the then government of Porfirio Díaz. “Porfirian peace and prosperity included the attraction of capital, and that brought many here,” said historian Jorge Alejandro Martínez Flores.”

The shape of her eyes, the color of her skin, and her clothes make MariaArgelia Komukai Matsui a living image of her past. “We are descended from Japanese people, we’re the third generation; my grandparents were the first generation, Komukai and Matsui both came from Japan,” she said, as she walked through Tapachula’s cultural center, where a group of children practiced martial arts.

“They came without knowing, without understanding. My grandfather said they came, they unpacked and they said ‘we’re staying here.’ They started to work and help those around them, they were doctors that helped many sick people, said MaríaArgelia Komukai.

The Japanese population in Chiapas goes beyond Tapachula. The municipality of Acacoyagua lies 76 kilometers towards the center of Chiapas, and at its entryway is a Torii Arch, which according to the Shinto tradition are the doors to another state of consciousness. On the arch is written “Place of important men,” another legacy of Japanese settlers in this part of the country.

In Acacoyagua’s central park there are murals of women with kimonos, cherry trees, and temples. And in the gardens, there is a monument recognizing those who brought Japanese medicine. Every corner of the region around Tapachula and the Soconusco is multicultural, this is clear in the food, the buildings, the activities people do and in the residents themselves, who are a living example of mestizaje.

Every historical era has particular traits, and in this region, since the end of the 20th Century, what we’ve lived is a new migration of people form at least 20 countries, according to the National Migration Institute (INM).

According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), between June of 2020 and July of 2021, 84 million people worldwide had to leave their country of origin. Over the same period, 18.3 million people in Latin America and the Caribbean endured enforced displacement.

The main reasons for this are violence and insecurity, as well as climate change. Most of the displaced are from Africa and Venezuela.

“The migrations that we are currently experiencing have a different context than last century. Today, the government has failed to create policies for the integration of migrants who come from abroad, principally from Central America, South America, and the Caribbean, and this marks a big difference with previous migrant arrivals,” said Jorge Alejandro Martínez Flores.

In Tapachula’s central park, in the offices where migrants fill out forms, in the other parks and streets of Tapachula, migrants meet every day. Most of them are waiting so that they can soon leave for the United States, while others are looking for the best way to stay.

Tapachula can be hostile, with severe temperatures and a lack of public spaces to socialize together. The struggle to get a job and housing at a fair price cause anguish, and sometimes a feeling of segregation between nationalities. Even so, taking a longer view can help us see threads of humanity and solidarity.

Yadira Alvarado arrived in Tapachula 20 years ago. The people accepted her as part of the community, she had a family and now owns a successful restaurant. For her, a woman migrant originally from Honduras, this is a good place to live.

“We started out with a little stand, selling in the area where we lived, then we started to deliver. A lot of people from Tapachula know us now, we’re well known for our food, people know that my husband is a carver, and both of my children are hair dressers. We’re known and loved, many people here appreciate us,” she said. As she spoke, she prepared the dishes that taste of Honduras, and which customers seek out in her restaurant El Rincón Catracho, which is in the center of the city.

The walls of her restaurant have murals that call up the landscapes she left behind, which she says she remembers but doesn’t miss. “Here in Tapachula I have a home, my children were born here, here I can walk around without any issues.”

Yadira is an example of someone who isn’t searching for the “American dream.” She’s just looking for a place to live, and she works hard to make it happen every day in Tapachula.

Yuderky Jules is 23 years old. She dreams of being able to study and never going hungry again. Her parents fled Haiti, she fled Venezuela. “They had to leave Haiti because the situation in Haiti has always been critical, the poverty is really extreme, if you earn money it isn’t enough to buy [the things you need], and sometimes when people have kids they can’t take care of them, so some older people couldn’t study, and that’s why they had to leave Haiti, because they could neither study nor work.”

But hunger and precarity followed her family to Venezuela. “I remember how, since there wasn’t rice, we had to eat damaged rice,” she said, in an interview in her apartment in Los Cocos, Tapachula, which has become a key area where Afro-descendent people as well as Central American migrants live.

“Getting here is really hard. The path is difficult, there’s so many mountains, rivers, the scariest thing are the thieves, the rapes, the kids who are dying in the rivers. It’s a horrible experience,” she said. Her memories tell her that whoever has gone through this journey, staying is a priority. That’s why Yuderky insists that locals must open up to new migrants.

“I think people from Tapachula can get inspired by all the stories that come to this society and which we can’t even imagine exist. Yesterday when I was walking downtown, on the pedestrian street, I heard people speaking in Hindi, in English, I heard a Chinese woman explaining to a Hatian man that she doesn’t speak Spanish, and I thought ‘this is marvelous, and we’re missing out,’” said Yamel Atihé.

She thinks that the racism and xenophobia that cause people to reject migrants are political strategies, not citizen strategies. “People from Tapachula can’t allow the loving and welcoming attitudes that have characterized us to shrink because of two-faced politics. It’s not our way, it’s the government’s way. The way of humanity that I’ve seen in Tapachula is one of openness.”

In this region, and in the world, we are living in a historic moment, a situation without precedent in our region, because of the amount of people who are arriving to save their lives, for freedom and for safety. This is a new opportunity to re-found Tapachula as a cosmopolitan and welcoming city.

This article was funded by the UNHCR-Factual grant on forced displacement in Latin America and the Caribbean.

This report was originally published by Chiapas Paralelo, which is part of the Media Alliance organized by Red de Periodistas de a Pie. You can read the original here.

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona