Survivors and victims of violence across generations demand access to military files and bases

25 septiembre, 2022

As families of the Ayotzinapa students demanded answers from the government, victims of the dirty war entered into Military Base Number 1, a place where crimes against humanity were committed.

Text by Kau Sirenio, originally published September 23, 2022.

Photos by Cuartoscuro, Kau Sirenio and Alexis Rojas.

MÉXICO CITY—Joaquina García is the mother of Getsemany Sánchez García, one of the 43 teaching students who were disappeared in Iguala, Guerrero, was clear in demanding soldiers bring forth information from their bases. She, like the rest of the families of the 43, wants to learn the whereabouts of her son.

We know that on this Military Base there are many things to clarify, there’s a lot of information they don’t want to give. What are they hiding? What are they defending?

Joaquina García

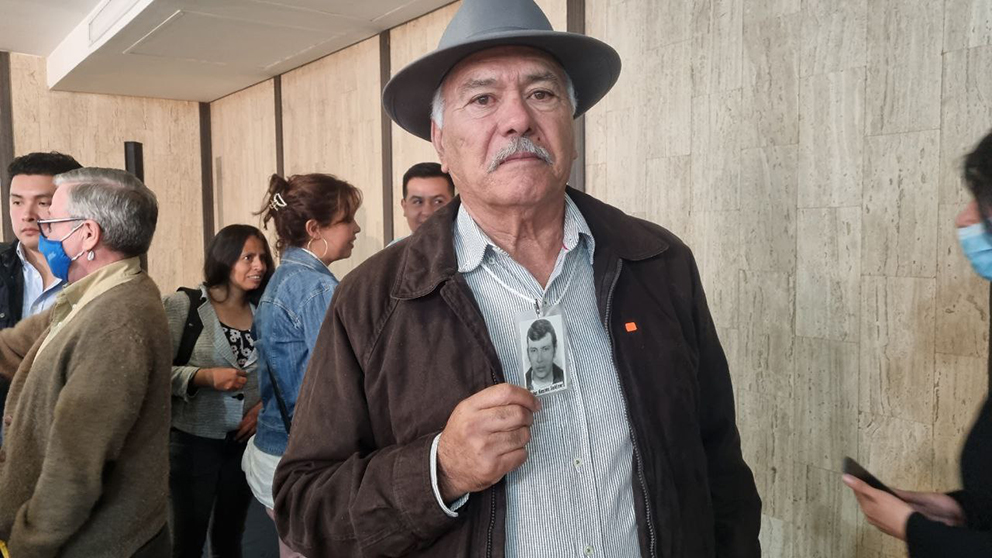

On the morning of September 23, 2022, during a press conference, survivors and family members of the dirty war, as well as members of the Truth Commission, spoke about what they found after three days of inspections at Military Base 1-A. They said there is “credible” evidence that serious human rights violations and crimes against humanity were carried out in the military installations.

Survivors and family members of the victims were present at the press conference. Felix Santana, the technical secretary of the Commission for the Access to Truth, Historical Clarification and Justice for serious violations to Human Rights committed between 1965 and 1990, said that those were were able to enter the Military Base were people who survived torture and enforced disappereance, as well as family members of the disappeared.

It took more than 50 years for the victims of the war to be able to access the military base. The information they presented after their entry to the base was that there was evidence of clandestine jails where guerrilla members, activists and university students were tortured.

They opened the door and they let us in, but they didn’t show us the places we wanted to see. Even so, this is a step forward, because we can start to understand what took place from 1965 to 1990.

David Fernández Dávalos, member of the Truth Commission

To this day, little is known about what happened on the Military Base. That’s what drives the urgency of the demand that information be brought out of the base on the part of one of the mothers of the 43 teaching students disappeared by the Mexican state.

“We recognized two areas and pieces of evidence. We’re talking about recognizing floors, basements, windows, scenery and underground rooms, that allow us to begin a deeper and more extensive process of investigation inside the military base and in other military installations,” said David Fernández, the former rector of the Iberoamerican University and a member of the Historical Clarification Mechanism of the Truth Commission.

Reclaiming History

The histories and the demands are the same, even though the moments and the places are different. “Hand over the information so the truth can be known,” was said on occasions. The first generation, that lived through torture and disappearance on the part of soldiers are working to change the narrative and undo the stigma that so affected activists and students.

The narrative that was built over decades was one in which members of guerrilla groups were cattle thieves, criminals, rapists and gang members. Meanwhile, the rural teaching schools were called Bolchevique Kindergartens and communist strongholds, and the students were called unruly, vandals, reds, and little guerilleros.

According to David Fernández Dávalos, it’s time to change the narrative.

It wasn’t a dirty war, even though that’s how we refer to that period. It was an operation to annihilate groups of people who were organized and who were struggling for a better society. It was a period of state terror, there was violence against people who were organized and who definitely didn’t anywhere close to the operational capacity that the State had in its repressive apparatus.

“To change the narrative, we have to show the truth about what happened,” said Fernández Dávalos during an interview with Pie de Página at the end of the event. “We have to recognize those who, in different ways, and some through political-military insurgency, others in political organizations, and others in social organizations, fought for a better homeland.”

He said that the achievements of these groups found expression in various changes in Mexico. “During López Portillo’s term there was electoral reform, then there was political reform, and that opened the path to the limited democratic system we have today. We have to recognize and name them, because they fought for democracy and fundamental freedoms. They are not social deviants or terrorists, as they were called during many years.”

The search for truth, past and present

The protest by the mothers and fathers of the 43 Ayotzinapa students took place on the same day as the capture of the rural teachers who took the Madera Barracks, in Chihuahua state, in 1965. Soldiers were involved in both events, which are marked by repression. That’s why, according to García, “We are asking them to give us any evidence they have about where our sons are, to show it to us. We are only asking that they tell us where our sons are, and what they did with them.”

The demand of the survivors of the dirty war, more than 50 years ago, is the same that is made by the parents of the 43 students: truth and justice.

We want them to put themselves in our shoes, eight years after the disappearance of our [sons] we want everything to come out, that’s all we want, truth and justice,” said García.

After García spoke, Mario Gónzalez did the same. He is the father of César González, one of the 43 disappeared students. “We’ve always said the disappearance of the 43 teacher training students, our 43 sons, was carried out by soldiers of the 27th Infantry Battalion. Now, the investigation is proving that’s true. I don’t know why they are covering for those members of the 27th Battalion, because they know when the exact moment was that our sons were disappeared.”

The narratives of persecution are connected to the infiltration of social movements. It happened in the 1970s, and it happened in 2014.

“[The army] had infiltrated the Ayotzinapa school. The infiltrator was on the bus with the 43 young men. They knew, because he was giving information to his bosses at the C-4 [military command center] in Iguala. I don’t know why they won’t hand over the disk with the information they have. I don’t know why they disappeared their infiltrator, why didn’t they activate a protocol to save their soldier, which could have saved the lives of our sons,” said González.

When the last speaker finished outside Door 1 of Military Base 1-A, the students graffitied the walls of the base. “It was the army” was spray painted on the main entrance. “Bring out the information,” they wrote, near the door where the soldiers enter the base.

Later, demonstrators threw stones and firecrackers towards the military base. The response came swiftly. The men in uniform threw stones and sticks towards the youth. When there wasn’t a single student, or parent of the 43 remaining, the soldiers sprayed water at the journalists and human rights activists who were gathered at the second door, near the Periférico highway.

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona