A photographer travels to Aldama, Chiapas–a place he has visited many times over the past years– to find the people who were injured in multiple and ongoing armed attacks that occur regularly out of the town of Santa Martha Chenalhó. The idea behind his visit is to do a photo shoot, focussed on pain and its imprint, with the hope of bringing new perspectives: that someone realizes they remain there, without support, with bullets in their bodies, violence materialized in metal and scars

Photographs by Isaac Guzmán, originally published March 26, 2021

Text by Leonardo Toledo

Translated by Pie de Página in English

It is said that a portrait is a moment of memory, an image that will tell of someone in a particular moment determined by time and circumstances. “That was him,” “that was her,” a portrait isn’t what people are, rather what they become when someone else or they themselves look at the portrait in the near or the distant future. They are to be what they were. The retractus stretches time, taking it back to the present of any possible later. The trahere holds the line, to avoid the victory of forgetting. These portraits tell and will tell that in the first months of 2021, these people were there, using their bodies against forgetting.

Whose bodies are these that we see? Do we recognize them? Do we recognize ourselves in their faces? Can we see ourselves in their gazes, which have dulled? Can we think of ourselves as being among them? Maybe it is easier to think about when a Sub-secretary presents them as numbers, in a power point where he affirms they are few, that they’re less, that they received their food assistance, while their aggressors received land, money, TV sets and impunity.

When we, city dwellers, look at the faces of the residents of the Indigenous towns of the high mountains in Chiapas, we see many things, but it is hard for us to see people. There is a fog, many layers of fog that confuse and diffuse the image. They are previous portraits, portraits we’ve made, portraits made by others of us. This image that we invented and over time we have convinced ourselves that it is authentic, the true self, the canon of their identity. Any image of Indigenous people is a heteroimage, which is to say an image made from outside, from afar, from before, from someone who is their other. All are the same, even if they’re different. We select them and put them in precious boxes, we discriminate against them to order the world as perceived, to the extent that we can no longer distinguish between one and another.

There are those who –thankfully– would say that what I’ve just affirmed is false. That they do see people, that it is an insult to say they’re interchangeable. That they know the person in the photo, that they’ve spoken with them, that that’s their best friend. That they know them and who they are. That’s why I must clarify that I’m referring to the image of people, not to the people themselves. That image that each person (every one of us) projects and is perceived by others, that image that doesn’t belong to us even though it is ours. I use Milan Kundera’s idea of authority to examine this texture, with some lines from his book Immortality:

It’s naive to believe that our image is only an illusion that conceals ourselves, as the one true essence independent of the eyes of the world. The imagologues have revealed with cynical radicalism that the reverse is true: our self is a mere illusion, ungraspable, indescribable, misty, while the only reality, all too easily graspable and describable, is our image in the eyes of others. And the worst thing about it is that you are not its master.

Such is it that the first person who sits for the photo session with Isaac in Aldama, doesn’t manage to relax, to “reveal themselves for the photo.” They’re not uncomfortable or nervous, they’re there on their own volition, as is the photographer, in fact they decided to do this project together. They want to tell their story, they want to be the narrators of their images, construct their self-image with someone with the technology and the training who is willing. But none of the photos convince the photographer, nor the subject-authors. It’s not the pressure, or the improvised photo studio they’ve built in the school (which was abandoned by teachers before the pandemic, for fear of another armed attack). It’s about talking of wounds, of bullets, of the violence they’ve suffered, their bodies as witnesses. It’s also about, they know, convincing, showing that it is true. But the body isn’t evidence enough. It hasn’t been enough thus far. That’s why, as they’re about to go home, that first person pulls out a document in which a doctor describes in clinical language what happened to him and his body. There’s no better way to say ‘this is me and these are my wounds’ than with this cold institutional paper, in these times in which the word of the health authority is nearly the only one to be heard.

How can colonized bodies narrate themselves? How to break with the occupation of this territory that is obliged to relate only what is expected, nothing more? Spectators and consumers of images hope they tell us the story we want or that we pay them for, nothing else, nothing different. For Susan Sontag, our consumption of images defines reality in a capitalist society, it is our form of being in the world, of living in it and transforming it. “Social change is replaced by change in images. The freedom to consume a plurality of images is equated with freedom itself.”

Just as the production of images isn’t unique to our times, neither is the imposition of those images. Portraits of others are always produced from a position of power, be they from a camera, a paintbrush or a pen. Whoever creates a portrait captures the subject from their point of view, from their perspective, from their vision of the world. That’s where the subject is framed, bordered, contained. There are few opportunities to respond, the portrait is taken and printed, and that’s how it will remain in the archives and be read by those to come. There’s even less of a chance to respond when those of whom portraits are taken don’t have access to the technology (the camera, the paintbrush, the pen) or to the techniques or the language. The portraitist is, at the best of times, a kind of interpreter, a translator between worlds. He shows his peers the far away other, distant and unequal. Just as Fray Bartholome de las Casas did those who lived in the lands he settled in his 1553 account A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies:

…this infinite multitude of Men are by the Creation of God innocently simple, altogether void of and averse to all manner of Craft, Subtlety and Malice, and most Obedient and Loyal Subjects to their Native Sovereigns; and behave themselves very patiently, submissively and quietly towards the Spaniards, to whom they are subservient and subject; so that finally they live without the least thirst after revenge, laying aside all litigiousness, Commotion and hatred.

How do you speak of yourself and your pain, if it is assumed you should be patient, without rancor or hatred? How do you show the anger about impunity and the absence of justice from an image of purity, bountifulness, calmness without any desire for revenge? There were other spokespeople, interpreters and defenders there too, they maintained the image of wisdom without malice. They were there, praying, making pilgrimages, walking four abreast, rebels; and at the same time, obedient and faithful.

A few years back in Aldama, it was decided that a man from the village would speak for the victims, for the injured, for the displaced. He took the role, knowing that he’d have to jump through hoops to make it happen. He disobeyed some, he ignored others, he contradicted many. He stood in the town square without interpreters or spokespeople, without permission, disobedient. Maybe that’s why he’s been in prison for a year, without due process, without witnesses, without flyers and marches to demand his freedom, without anyone adjusting their plans to support his cause. “Let Cristobal go home!” yell some isolated voices, that do not reverberate.

Early last century the photographer Guillermo Kahlo was in Chiapas, tasked with creating a typology of Indians. The governor sent a family from each town to a studio that the photographer set up. That’s where they had their portraits taken, in their best clothing, after traveling for days through forests and mountains. In some cases the portraits were of just one person, because the whole family didn’t manage to complete the trip. Is that why, in the Porfirian inventory, the records say “in that town a family is made up of a father and daughter,” “in that other town it’s a mother and two sons”? These portraits were part of a pattern, they defined and froze in time the being of the peoples of Chiapas. That’s who they are (not ‘who they were’), that’s how they dress (not ‘how they dressed’), that’s what they’re called (not ‘that’s how they used to be called’). A catalogue of uprooted bodies, without will, positioned in a foreign scene, barely decorated with two potted plants that serve as a frame. Speaking of family, a few years later, the daughter of this photographer would say, of her own body:

My body is wasting. I cannot escape it. Just as an animal senses its death, I feel mine has already installed itself in my life, to the extent that it has taken away my ability to struggle. My body will leave me, leave me, as I have always been its prisoner. A rebel prisoner, but a prisoner all the same. I know we will mutually annihilate each other, the battle will have no victor. It is a vain and permanent illusion to think that thought, in fact, can liberate itself from this other material that is meat.”

Photographer Isaac Guzmán questions himself on his own production of images in front of the victims of violence in Aldama. The original idea of focussing just on the scars that the bullets left is quickly thrown out. He is worried about replicating images produced by physical anthropology last century, hard, cold, measuring bodies from a biological perspective, cataloguing them, creating taxonomies of colonial domination. He also recognizes the use of cameras as a means of controlling bodies, of enforcing domination over the other. But his fears are quickly vanquished by the determination of his subjects to take control of the situation. They propose ideas, show their scars without shame, pull up their shirts, pull down their pants, adjust their blouses to show the insulting marks. A woman and her son introduce themselves, she pulls down the child’s pants to show the bullet scar in his buttcheek. The photographer becomes shy, as he knows who will be on the other side of the image. He asks her to pull the pants back up. “It’s enough for him to stand sideways and show with his finger where the bullet hit,” he manages to say.

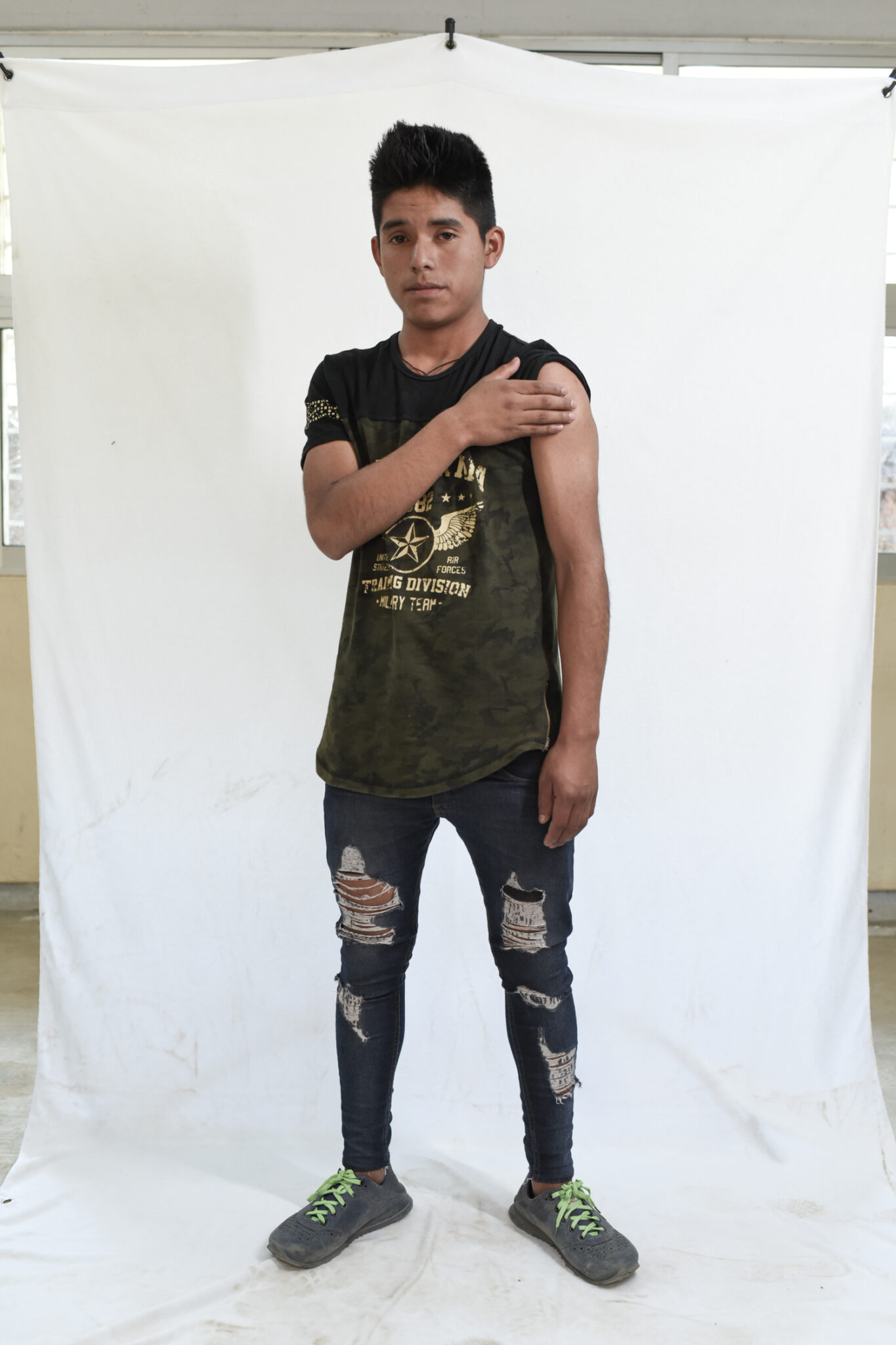

They show one scar after another, each accompanied by a story, a memory. One of the women’s husband’s was killed. Another man still has a bullet in his rib. A couple chats as they are photographed, telling the story of their displacement, narrating how for the last two years they can’t enter their smallholding, they can’t cultivate coffee, they can’t live normally (neither the new normal nor the old normal). A young man decides to pose in a way that is extremely rigid, like a tree. He was shot while he worked in the fields, he tried to run away and as he fled he fell and fractured his femur. He still can’t walk properly, every step hurts. He hasn’t been able to go back to work the fields. A boy was playing with a ball when he was shot at, he was alone at home. The bullet grazed his neck, but because of the lack of medical care the wound grew, now he has an enormous scar, puffy, impertinent, contrasting with his sullen face.

We don’t see people, we see images from the same vantage point where were saw these same bodies exhibited on postcards for tourists, from where we saw the hidden faces, the brave and drawn faces of 1990s photojournalism, which sustained the idea of beings with a predefined personality and interchangeable faces. Our expectation of a supposed identity is significant, we hear the stories of these scars, but we tell a story of attributes and defects that comforts us, a story we already know. It brings to mind what Elisa Ramírez Castañeda wrote in her book Photographers and the Indigenous in 2000:

This particular selection of photos is associated with images that have long occupied eyes and memory –those considered the ethnographic and canonical representation– and with them we are met with new information inside a defined mental space. They are Indigenous, precisely because they correspond to their representation, a historically created archetype, an outdated model.

We move from this canonical representation to the portraits of victims from Aldama. But this time, they interpollate us by showing their wounds, their scars. And not in a symbolic way, nostalgic for paradise lost, but rather raw, exposed, inappropriate. There is no request for sympathy or commiseration, rather a demand for justice, a demand in the face of the unpunished violation of their bodies, of a state that avoids them, that awards their victimizers, with medical doctors from the big city who says it’s better if the bullets stay in their bodies, bullets that go back in every day, that invade, that stain, that are at the once threat and memory. Sullied and invaded bodies, again and again, every day, without exception.

In one of the photos Isaac appears in front, and a boy with an empty stare shows a scar under his knee, behind him there is a poster that reminds us of the institutionalized educational discourse about bodies. State discourse enters and interferes with individual discourse, which we can’t read or hear. There’s nothing there where a reader of images from the city recognizes themselves, except for the poster. There we all are. That all that never manages to find itself in the wound of the boy, much less in his stare.

So… Who is looking when we look? What do we say to ourselves when we see those looks? We live in times when technology is not a limitation to creating portraits and memories, there’s more cameras than people, the selfie (the self portrait, so rare in times of Fray Bartholomé) floods public discourse. The heteroimage, the construction of the image of the other no longer depends on the writer as on the reader. We are, in reading the image, authors of the portrait, we establish the limits, we attribute virtues and defects that don’t exist onto a field of pixels. This other who takes the camera and explains to the cameraman, and the image says “it’s me, it’s me” and it appears immediately on our screen at home, on our cell phone, and we are the ones who decide and define –from a place of power related to ‘possessing’ the image– the amount of fog that we’ll place in front of it, until it becomes distant and incomprehensible or until we recognize ourselves and share the outrage. Are we the same body, trapped in violence, unbearable violence? Can we feel that same stray bullet that is a daily reminder that the body is under siege, under fire? Or do we stay distant, marking from our individual will a murky imagined difference, built through centuries of monologues? Is it possible to continue saying ‘I’m me and he is other, worse for wear in a distant forest, while I’m an immaculate, solitary tree that will become a violin?’

Too many questions,and their answer is not found in Guzmán’s photos or in this text. It is worth remembering what Elisa Ramírez said as an affirmation-condemnation in the text cited above: “The ghost of distances and inequalities prevents the other, as a hypocritical reader, from being my equal, my peer.”

This report was originally Published by Chiapas Paralelo, which is part of the Media Alliance organized by Red de Periodistas de a Pie. You can read the original here.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona