Reviving Mexico’s modern ghost towns

9 abril, 2021

The federal government has proposed recovering 600,000 units of social housing that were abandoned nearly immediately after their sale over the last 20 years. In these areas, residents who remained have organized to live without water, electricity or sewage

Texto: Arturo Contreras Camero, originally published March 30, 2021

Photos: Duilio Rodríguez

Translation: Dawn Marie Paley

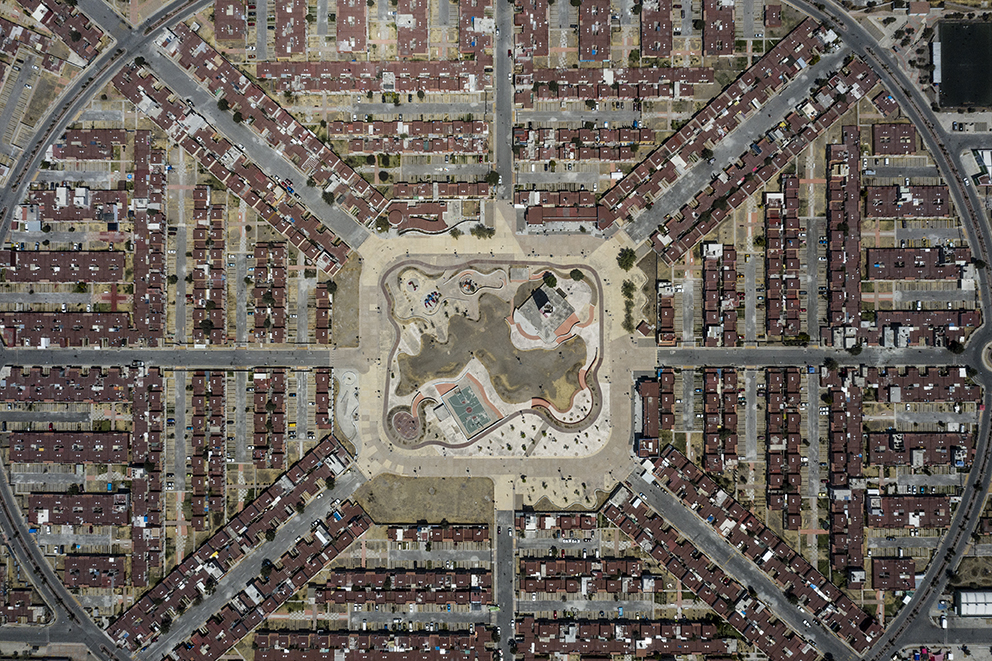

ZUMPANGO, MÉXICO STATE.– On a map, the neighborhoods look amazing. Symmetrical subdivisions with a radial design and closed residential streets. But upon visiting, one finds phantom streets, with rows of identical houses, abandoned and looted, as well as houses with the windows covered with plastic bags and sheets for doors, as if their neglect was an open invitation. Dotted among them are homes where the owners stayed put, after having invested more than money, time, and life.

Until a few years ago, the official version was that these houses were abandoned because their owners couldn’t pay their mortgages. But the lack of urban planning, poor construction of public spaces, and the lack of essential services also played an important role. By the end of 2018, Mexico’s Institute of the National Workers Housing Fund (Infonavit), counted nearly 661,942 houses abandoned under these conditions in Mexico. Another figure, from Mexico’s National Evaluation Council of Social Development Policies, suggests there could be as many as five million.

The houses in the Santa Isabel subdivision in Zumpango, Mexico State, are an example of these types of immense areas of cookie cutter houses that look like they were cut out of cardboard for a miniature model. Their location is likely the first problem. They were built in the middle of nowhere, so far away that people that lived here would have to spend the majority of their daily wages on transportation. “That’s why many people don’t come live here, because the District (Mexico City) is really far away”.

Photo: Duilio Rodríguez.

The person speaking is Ana, who has lived in this residential subdivision for more than 20 years. “The problem isn’t just the distance time-wise –on a good day, it can take as little as 50 minutes– but the cost of the trip, which is very expensive. It’s about $120 pesos (US $6) per day to come and go.” Beside Ana’s house there are two others that are abandoned. “When I arrived here there was nothing at all, no electricity or water, but the issue of transportation was central. At first we would go around pleading for a bus to take us”.

When Ana bought her house she never thought that Homex, the company that promised her a home with electricity, water and sanitation, would leave her living in an unfinished subdivision without services. That was what caused many people to leave their homes, giving way to a massive invasion.

Organization, in the face of forgetting

A few blocks away from Ana’s house is a street full of houses that are lived in, but not by their legal owners. Rather, the tenants are people who need housing and can’t afford it. Some of the neighbors in Santa Isabel developed a method to prevent such invasions, which are sometimes taken advantage of by criminals.

If one of the residents notes any sign that someone from outside the development is living in the houses or wandering around, they immediately warn the others. Sometimes they do so through a Whatsapp group, other times, they use a whistle. In silence, from their homes, they evaluate the situation and decide how to proceed.

That’s how they approached these two journalists as we walked out of an abandoned house towards the street. “Good morning! Who are you, what are you looking for? Is this house yours?” they ask from a distance. After we introduce ourselves, the neighbors start to describe the challenges of living in a subdivision that has been forgotten by those who built it, by the government, and by many of its residents.

“The owners have never, ever come, they don’t even care, it’s up to us to care about something that isn’t ours,” says a man in a Cruz Azul jersey, shorts and flip flops, who later introduces himself as Raúl. He’s immediately interrupted by another woman, wearing pajama shorts and a sleeveless camisole, all in pink. Her name is Iris Zita. “Now that the rainy season is coming, for example, there are flies, caterpillars, and snakes and it’s us who are out there cleaning, sweeping everything, clearing it away.”

“We organize ourselves, quote unquote,” says Raul. “There isn’t a classic structure, it is more like communal work.” As if they were on the same wavelength, Iris Zita replies. “It’s simple, I don’t want the weeds grown over and I don’t want spiders in my house. When people arrive from elsewhere, and they see that it looks cleaned-up, we don’t run the risk that they come and take over; if they see everything trimmed down, they’ll say no, someone lives here.”

“We even trim the trees! There were people who wanted to take over the houses and they would hide in the trees until night,” said Raúl.

This group of neighbors looks after their “U,” as they call the shape of the street they live in. It’s a small area, made up of about 30 houses, in a subdivision of more than 500. They estimate that 60 percent of the homes here are abandoned.

Homex: The construction firm that fled before completing the job

After we chat for a while, the neighbors begin to speak more openly. “We don’t have anybody, we’ve been abandoned,” said Iris Zita, angrily. She refused to be photographed, ashamed at wearing pajamas. “The area, some say it already became a municipality. But it doesn’t seem to belong to anybody. The receipts for our property tax don’t say Santa Isabel, it has another name.”

Indeed, the subdivision she lives in doesn’t legally exist. When she pays her property tax, the receipt shows with the name of one of the nearby subdivisions, and the same goes for her neighbors. These are some of the long term impacts that the construction company Homex created.

Housing companies, unkept promises

This subdivision, like many others, was built by Homex, a company that together with Casas Geo or Urbi, underwent a massive boom during the 2000s. With the arrival of the National Action Party (PAN) to power, they began the construction of hundreds of thousands of housing units around the country, but when the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) came back to power, these companies went bankrupt. Many subdivisions, like Santa Isabel, were abandoned, left half finished with a pitiful lack of basic services.

In this subdivision, until a few years ago, there were no power lines. It wasn’t until some residents built their own that the electricity meters were installed, many houses still don’t have them. Water supply is lacking and there is no sewage system. At times, a nearby canal of untreated sewage overflows and fills the houses with a layer of liquid waste of up to a foot deep. There’s no phone lines, just satellite service and cell phones, but the signal is terrible.

Even though the subdivision was slated to have more than one school, the construction company only built the elementary school. The recreational center was never finished, its half built shell stands over the remains of the center of the former hacienda.

“They were going to build a pool here, where it says stop” said Iris Zita as she pointed towards the end of the street. “This land belongs to Homex, there’s always people watching it. There’s some that look after where the pool was supposed to be, but there’s nothing there.” She says the pool was one of the reasons she bought her home there. “My daughter was very excited, she told me to buy a house near the pool, and that she would take swimming lessons in the recreation center.”

Iris Zita, resident of Santa Isabel, Zumpango.

The perversion of Infonavit

What has happened with Infonavit is a disgrace, according to architect Luis Antonio Urias, who doesn’t mince words as he described the events. “It wasn’t just corruption, but a whole series of a kind of neoliberal policies, which today remain dominant. A series of measures were adopted which privileged the sale of homes over the demand for them. In a very subtle manner, because they never said it, [Infonavit] became a financial organization, to me that’s the crucial point.”

Urias is currently a professor at the University of Sonora, where he teaches courses on construction and the history of housing in Mexico. Ever since he was a student at the Autonomous National University of Mexico he has dedicated an important part of his scholarship to studying social housing. In 1989, he received a prize from the World Bank for developing a system of remunerated self-construction.

“If you read about how Infonavit was created, it was one of the best government institutions in Mexico,” said Urias, who is also a PhD in architecture. “But what has happened between the time of [Carlos] Salinas and today? They converted it into a financial company, more concerned with money than with people. Before ‘92, in the Law [regulating] Infonavit there was no way to repossess a home because of missing payments, it couldn’t be done. They had to wait until that person had an income again, but when [Infonavit] became a financial organization, that change was authorized.”

“That’s how Infonavit started to repossess houses,” said professor Urias. “It paid for lawyers, they brought lawsuits and they removed families from their homes, but it turns out that they didn’t have the infrastructure to look after those homes, to care for them, and since the paperwork to reassign [the homes] was not straightforward, what happened to the houses? Infonavit also ended up abandoning them.”

When it began operations, the Institute for Housing Promotion, which operates with five lines of credit, privileged one in which the Institute would develop its own housing units. That line of credit disappeared in 1992 and a new one was created.

In this context, credit line two was opened, in which the developers build the housing and offer to sell it to Infonavit and it goes through an authorization process. When Infonavit authorizes the agreement, it commits to pay the developer, and the developer is the one who agrees to bring customers seeking housing to Infonavit.

Regarding potential solutions to this residential juggernaut, professor Urias notes that there is a path forward that has thus far not figured into the federal government’s vision to rescue Infonavit: find out what happened to the families who lived there and were dispossessed, and then create mechanisms to reassign houses to those who need them most.

The new airport and the promise of growth

On March 3, 2021, all the police cars that hadn’t been seen for a long time arrived at the Santa Isabel subdivision on a single day.

There was a major operation, the [director] of Infonavit and the [secretary] of Sedatu [the Secretariat of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development] arrived. They arrived with like 10 police cars, and who knows if it’s true or not but they came in, they ate, they went around and the people from Sedatu met behind closed doors with Gamboa [the mayor]. They didn’t say anything to us, but we knew they had signed the contract, that they were going to improve the subdivision, put in street lights, and that Infonavit would be in charge. There was no meeting with the residents. They basically told us to leave our homes. There were state and municipal police and the National Guard, and they locked down the entire elementary school.”

-Antonio Martínez, resident of the Santa Isabel subdivision

According to an announcement by the head of Sedatu, Román Meyer Falcón, there are 250,000 abandoned homes in the seven municipalities that surround the new Felipe Ángeles airport in Mexico State. In Tecamác and Zumpango alone, there are around 50,000, of which they are planning to recover 40 percent. In addition, Sedatu proposed a special Program for Urban Improvement aimed at those seven municipalities, with the goal of generating local jobs.

Since the government’s announcement, it seems a parallel market is emerging, which could feed residential speculation in the area as a consequence of the construction of the new airport. Not far from the Santa Isabel subdivision is another subdivision called Las Plazas, which was completed and has street lights and public recreational spaces. Among the houses, people have all kinds of small businesses, including computer repair, produce stores, poultry shops and corner stores. At the entry to Las Plazas, there is a small mall where a real estate company has it’s office.

“In our area, we’re seeing that many people are looking for houses around here,” said Juan Mía, a real estate agent. “There needs to be change. We’re all waiting for it but it hasn’t come. They’re working day and night, but they still can’t [afford a house], we’re certain that the airport will have an economic impact in the whole area.”

“Lots of people are looking to live nearby, they’re looking for houses. The businessmen, they’re looking for lots to buy hotels, restaurants, malls, all of that. [Property values] have to go up. They will go up unless another President comes along and moves the airport to Toluca.”

This office is dedicated to reassigning the mortgages of some of the houses that are abandoned, but also of those in which the owners are present. “I’m looking for someone that wants to pay for it. If you have an Infonavit credit, I’m looking for someone that also has one and who can pay your debt, and if you, let’s say, make a profit, you’ll get that back,” said Ivonne Ramírez, another agent in the office. “I’ll do the paperwork with the institution, and I’ll tell you: you have to do this, this and this, and we’ll do the paperwork. It takes me from 45 to 60 days. Then I’ll go to a notary and another person will be assigned the house, that’s what I do,” she said pleasantly, in the voice of someone making a sales pitch.

Abandoned homes, an option for those without

Zumpango is the municipality with the third largest number of abandoned Infonavit houses in the country, after Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua and Reynosa, Tamaulipas. Among the more than 13,000 abandoned homes, it is common to see sun-worn signs that say “for rent” “for sale.” Santa Isabel, which has more than half of the abandoned homes, is still a liveable development, regardless, there are others like Santa Cecilia where the solitude seems to cover up for unspeakable crimes.

The two developments are connected by a highway that isn’t finished, parallel to which are a series of avenues. In between the streets, separated by dusty median strips, there is a collection of tin shacks clustered into an improvised market. In the midst of the noise from traffic, Guillermo Alcántara and one of his friends wait for a repair in a tire shop that looks like a newspaper stand.

“Ah yes, all these houses are unoccupied and they’ve been stripped because the owners never come! They rob them, they vandalize them, they take the windows and everything else, and they sell whatever they can, then no one wants to live in them because that’s also dangerous.”

Guillermo Alcántara, resident of Zumpango.

“Just imagine! The insecurity here is so bad that, dang! I sell small blenders, when I used to live by the tower over there, I would put out a table and display the blenders. And this guy showed up, and he said to me ‘…I’m from the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación, and guess what? I’m going to charge you rent now,’” said Alcántara, puffing up his chest and lowering his voice to imitate his would-be extortioner. “I mean, just imagine how bad insecurity is here! I told him it wasn’t my house, that I just started living there recently, and that I really don’t sell very much. I told him to take the blenders, it was the only thing there was. He didn’t want them, and so he left.”

Alcántara spoke in an animated way as he narrated what the different subdivisions are like. “Santa Cecilia!” He exclaimed, as if surprised, while his friend made a hiss that sounded like air escaping a punctured ball. “No, over there it’s super… I live over there, you know. The house I’m living in is abandoned and it has Polish air [cold drafts] all over the place, because there are no doors, no windows, no toilets, they just leave the shell and you have to fix it up as much as you can.”

Guillermo has lived in Zumpango for two years. He moved here after being ripped off by a crooked politician from Mexico City, but he tells the story so quickly it’s impossible to get the details straight. Like him, there are people who have been occupying houses for six or seven years.

“There are people who have put up doors and railings, who fixed up these houses. I mean, they’re abandoned, the people living in them aren’t vandalizing them,” he said. A long silence followed, as if he remembered he’s living in a home that isn’t legally his. “And if [the government] comes and fixes them up, what will happen to me?’

Arturo Contreras is a journalist on a constant journey to find the best way to tell each story, and in this way do a service to citizens. He analyzes databases and make graphics, and tells of experiences in a way that makes sense of our reality.

Duilio Rodriguez is a photographer and editor interested in art, cinema, architecture, literature, rock climbing and spots in general (except soccer). duiliorodriguez.com.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona