1 abril, 2022

The suspicious death of Pedro Carrizales, better known as El Mijis, forces us to see an ongoing problem in Mexico: the abuse of power by police departments, which violate the rights of many on a regular basis.

Text by Marcela Del Muro, originally published March 18, 2022.

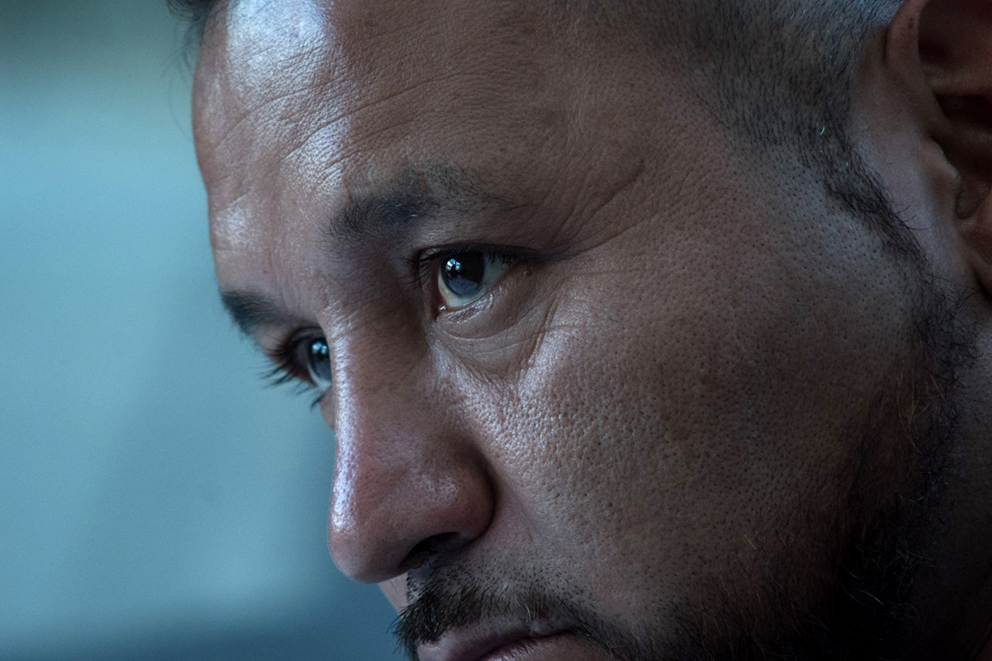

Photos by Mauricio Palos.

Translation by Dawn Marie Paley.

SAN LUIS POTOSÍ—El Mijis “never traveled alone,” according to Frida Guerrero, an activist, journalist and close friend of former congressperson Pedro Carrizales Becerra. She spoke during an appearance on the Momentum news show on March 4th.

He never traveled alone, but on January 31st he decided to do so, because it was a short trip, just three hours by car. Pedro left Hotel Las Fuentes in Saltillo, Coahuila and headed out towards Monterrey, Nuevo León. Before he left, he told his wife Miriam he’d come back to the hotel with her and their children, around one in the morning. That was the last time his family saw him alive.

El Mijis was retracing and mapping the route from San Luis Potosí to Monterrey in order “to be able to launch a migrant support campaign,” according to Frida.

The day after he left, Pedro contacted his wife to ask for the reset code for one of his two cell phones, and he promised to call back. On February 2nd, Miriam received the final voice messages from Pedro: “My love, I’m on my way. Thank God they released me, the police had me, the GAFES (special forces from Coahuila), I thought they were criminals.”

During 30 days, Pedro was disappeared. His phone’s location was traced to Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, on February 5th, 8th, and 15th.

But, according to the official version, the activist was in a fatal accident at kilometer 27 of the highway between Piedras Negras, Coahuila, and Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas. The accident occurred at dawn on February 3rd. Due to high speeds, his red truck flipped and lit on fire in a drainage ditch beside the highway. Pedro was more than three hours outside of Monterrey and about four hours away from the hotel where his family was waiting for him.

The remains of Pedro Carrizales, who is better known as El Mijis or Pedro Piedras, were returned to his family on March 2nd inside the morgue in Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas.

“There’s so many questions,” said Frida, who confirmed that Carrizales Becerra’s family is also questioning the official version. They aren’t the only ones.

«The Attorney General’s Office in Tamaulipas can’t be trusted, because on serious issues, on sensitive issues, they’ve falsified information,» said Raymundo Ramos, the president of the Human Rights Committee of Nuevo Laredo.

Doubts about the official story

Frida says there were two meetings between the Carrizales family and the Tamaulipas AG’s office. The first was on Friday, February 25th, and the second on Wednesday, March 2nd.

The second meeting was long and painful for Miriam (Pedro’s oldest daughter), his assistants and Frida. During seven hours, they listened to various investigators explain how Carrizales Becerra died.

“The truck matches, according to the serial number,” said Frida. “They gave us their version, that he was speeding,” but none of them could provide an estimate of how fast he was driving when he lost control of his vehicle, before he fell into a drainage ditch a meter and a half deep. “It was a really short distance, as if he had hit something.”

His family asked: “If he was going so fast, why didn’t his truck go flying.” None of the investigators could answer.

The crash led Pedro to fracture his back at the T12 vertebra, in the thoracic area, which sliced his abdominal aorta, the most important artery in the body.

“He lost all his blood, all five liters, in one breath. He died in less than a minute. That’s why there was no soot in his lungs: he was already dead when his truck lit on fire,” said Frida. The fire, according to the AG’s office, started in the battery, “that’s where the fuses are and boom, the truck lit up.”

In another interview with journalist Julio Astillero, Guerrera said that no one in the family was able to see the burned truck, but that they were given the damaged papers that were found inside. Papers that somehow survived the same fire that charred Pedro’s body.

Most of his body was completely burned, just one part was charred. That’s where they were able to take a DNA sample, according to the family. The AG’s office was unable to explain how hot the truck had to have gotten for his body to end up like that.

“They said he was driving on that highway, but we can’t be sure it was him,” said Frida. El Mijis, she said, “had no reason to be there.”

What the official version can’t explain

El Mijis’ plan was to travel 90km from Saltillo to Monterrey, but the phone he had was located in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, more than 260km north of his destination.

“On February 25th, the Tamaulipas AG accepted that on February 5th, [one of Pedro’s phones] made a call originating from Nuevo Laredo. And on February 15th, when his wife was with Rosa Isela [Rodríguez Velázquez, Secretary of Security and Citizen Protection], she got an alert that that phone had been activated,” according to Frida.

Nuevo Laredo is a border city that has been a focal point of disappearance and violence over past years. A recent example of how came on March 14th. That day, the city became a war zone due to a series of operations carried out by the Specialized Attorney General for Organized Crime (FEMDO), in which Juan Gerardo N, one of the heads of the Noreste Cartel, was captured.

But “if the congressperson had been in an accident immediately after leaving Coahuila, flipped his truck and was burned to death, how is it possible that his phone was turned on and off in Nuevo Laredo? That means it was stolen from him,” questioned Ramos.

The last to see El Mijis alive

Frida Guerrera affirms that the last people to see El Mijis alive were the police officers that detained him. They are part of an elite force known as GATES, which translates as a SWAT team. They are part of the State Security Commission in Coahuila.

In the last voice message he sent, when Miriam was in a panic trying to locate her husband, you can sense the worry in his words:

“I couldn’t talk because they were detaining me, and what I want is to get out of here now.”

El Mijis

Frida thinks that “because of his tone of voice, it was obvious that he wasn’t alone and that the authorities weren’t giving the situation the importance it deserves.”

Those messages, according to the activist, were also traced to Nuevo Laredo.

Ramos explains that on the road between Piedras Negras and Nuevo Laredo, “as soon as you enter Coahuila, there’s three state police checkpoints, and it’s very likely that he was detained in at least two of them. We have denounced the police in Coahuila for human rights violations: arbitrary detentions, torture, sexual violence and enforced disappearance.”

The area where Carrizales is said to have crashed is constantly being overseen, because there is an international border bridge in the town of Colombia, Nuevo Laredo, where there is an encampment of marines. It’s an area about 20km long, where three states meet: Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.

Elite Coahuila police, specialists in human rights abuses

After the declaration of the so-called war on drugs by then-President Felipe Calderón, Coahuila’s governor Humberto Moreira implemented the Coahuila Model. This “consisted in assigning military officials who were retired or on leave to take over police forces of certain municipalities and of state security agencies,” according to the Mexican Commission for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (CMDPDH).

At that time, the state was experiencing very high levels of violence. Part of the state was occupied by Los Zetas.

In 2009, the Immediate Response Group (GRI) was created, and tasked with containing violence and confronting organized crime in the area.

“That organization was the first of various special forces that were highly militarized, created without a clear legal framework, and without clarity behind its creation, organization or specific functions,” according to the CMDPDH.

In 2011, the GRI was disappeared and the Special Weapons and Tactical Team (GATE) was created, as part of Coahuila’s State Security COmmission. The Commission was headed by soldiers.

The CMDPDH says that the GATES “received intensive training carried out by ex-soldiers who were part of an elite unit of the Mexican Armed Forces, together with soldiers from Spain and Israel.”

From the first years of its creation there were complaints of human rights abuses by residents who had been detained by members of the GATES. Coahuila’s State Human Rights Commission (CDHEC) notes that, between 2012 and 2015, there were 1,005 complaints made against the GATES.

Given the complaints around human rights violations, the response of the government of Coahuila was to change the name of the force. They became Fuerza Coahuila, Action and Reaction Police, and otherwise. Regardless, many members continued to participate in operations even after the name change.

Torture, disappearance, murder and framing

Looking over the recommendations emitted by the CDHEC against the Special Weapons and Tactical Team, one finds a series of horror stories.

The Commission started an investigation based on a newspaper article that read: “a resident of the first neighborhood of Villa de Cloete was killed after being detained by the Accredited State Police and the Special Weapons and Tactical Team in Cloete,” according to recommendation 23/2017.

On September 5, 2017, between 10 and 11 at night, the parents of the murdered youth were told that their son had been detained in a pub in Villa de Cloete, in the municipality of Salinas. They went to the scene, but a GATE agent threatened the father, and they decided to leave. On the morning of September 6th, the couple went to the municipal police offices. Their son’s truck was parked out front, and they expected to go and pay a fine and take their son home.

“We told them we were his parents, and they said ‘your son is at the Red Cross [Hospital].” The mother asked what happened, and the police said “prepare yourself, your son died.” The municipal police told the family that they didn’t pick up the young man, they said they were informed that he died of a heart attack in hospital.

Of all the recommendations reviewed for this story, most involved arbitrary detentions and torture, used so that people in custody would confess to crimes they didn’t commit. Also, in most cases, agents planted objects like guns and drugs on the people they detained. Regular, everyday situations like going out to eat with your children or going to work in the morning became moments of danger, especially for young men, in the state of Coahuila.

“In Coahuila, they’ll tell you there’s no cartel. In Coahuila, these assholes (elite police forces) are the cartel,” a member of the GATES told El Universal journalist Íñigo Arredondo.

The GATES arrived “like a succession of arms and drug trafficking, faked confrontations, altered crime scenes, extortion, kidnapping, and torture of the coyotes who cross migrants to the United States.”

According to Raymundo Ramos, “for the last 10 years there have been permanent checkpoints of elite special forces on all of the highways into Coahuila.” During this time, the Nuevo Laredo Human Rights Committee documented approximately 40 cases of violations committed by the GATES.

“It’s a very repressive group, there’s a lot of abuse of authority.” Raymundo recommended not traveling alone in Coahuila, “and especially men or women traveling alone; at the checkpoints, everyone is a suspect.”

Tamaulipas and the cover-up

Frida thinks the only way to know what happened to El Mijis is for the Federal Attorney General’s office to carry out an in-depth investigation, because there’s no way to trust the Tamaulipas AG.

Raymundo thinks the way Pedro’s body was found is strange. “I don’t trust the official version of the Tamaulipas Attorney General, because we have documents that prove they’ve lied. I’m not confirming this was an extrajudicial killing, but we have documented extrajudicial killings which, often, were perpetrated by police officers,” he said.

The Committee has represented families of victims of enforced disappearance and extrajudicial killings by members of the Marines. Between December 2017 and May 2018, the Special Operations Unit of the Secretary of the Marines carried out an operation in Nuevo Laredo that resulted in at least 45 disappearances, of which 21 were later found dead.

Mexico’s Attorney General has 34 investigations open connected to these disappearances, and 30 marines are facing charges. Of them, just 18 are currently in prison.

“The move by civilian authorities to investigate and lay charges should be carried out alongside measures by the [Secretary of the Army] to avoid the repetition of these kinds of events,” said the UN regarding the case.

Raymundo also pointed to events in January of 2021 in the city of Camargo, Tamaulipas, where 16 Guatemalan migrants, two Mexicans and one Salvadoran were massacred by 12 state police. Some of them were part of a special operations group called the GOPES, which is similar to the GATES. “After the killings, the police officers burned their bodies to hide the evidence,” said the activist.

Protection, truth and justice for the Carrizales family

In the President’s early morning press conference on March 17th, Frida Guerrera asked Andrés Manuel López Obrador for help to ensure Miriam is incorporated into “some kind of system of protection by the mechanism [to protect human rights defenders], because she’s alone with her babies. She doesn’t live at their house anymore, out of fear.”

The official version is that Pedro Carrizales died in a car accident, but it’s not only his family, Frida and Raymundo that doubt the Attorneys General of Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, Coahuila and San Luis Potosí version of events. His death has sparked debate on social media, and in some traditional media as well.

Pedro was more of an activist than a politician, he himself said so. As a congressperson, he brought much needed issues into the media and into politics, many of which were uncomfortable for governments. His proposals may not have been approved, but they are still being discussed, defended or remembered.

The death of Pedro Carrizales Becerra leaves many questions open. But it’s also brought to the fore the constant abuses of police forces in México. Forces that arbitrarily detain, torture, carry out enforced disappearance, kill, and constantlly abuse their power. Until the very end, El Mijis brought out issues that are very uncomfortable for the state.

Marcela del Muro is a freelance journalist based in San Luis Potosí. She likes to write stories and hold on to them, that’s why she’s a journalist. Her work is centered on human rights, migration, disappearance, gender violence and the environmental crisis.

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona