Dozens of families who are saerching for their disappeared loved ones visited prisons and scanned identification sheets for dead bodies as part of the Sixth National Search Brigade for the Disappeared in the state of Morelos. Inconsistencies and omissions from state authorities hindered their efforts.

Text and photos by: Estrella Pedroza, originally published October 23, 2021.

Translated by: Elysse DaVega for Pie de Página in English.

MORELOS– Not all people who are disappeared are killed. Sometimes they’re exploited, worked until their body can take no more; other times they’re imprisoned for crimes that they didn’t commit.

Experienced searchers know this fact well. These experts are mothers, daughters and sisters who, faced with authorities’ failure to act, left their homes to search for their loved ones, doing their own investigations.

«This is why it’s important to dig through files and in places where few have access, like prisons and mental hospitals,» a woman searching for her missing daughter explained. She suspects that her daughter is a victim of human trafficking.

Her goal is to find clues that will help her find missing and disappeared people.

This is why, along with dozens of other family members also searching –most of them women– she showed up to the Morelos state prosecutor’s office on October 9th with high expectations.

«The Morelos government promised us that they would provide all of the necessary resources to carry out the search,» the same woman emphasized, clutching her daughter’s photo to her chest.

She prefers not to give her name, but she’s part of the Sixth National Search Brigade for Missing Persons, which, like in other brigades, has incorporated prison visits as part of their search for those who could still be alive.

During this search outing, they looked through the files of unidentified persons whose bodies are held by the Forensic Medical Service (Semefo) in Morelos.

The Brigade is composed of families hailing from 26 different states and representing 160 different victim support collectives. Still, their expectations began to fall from day one.

Information «not suitable» for searching families

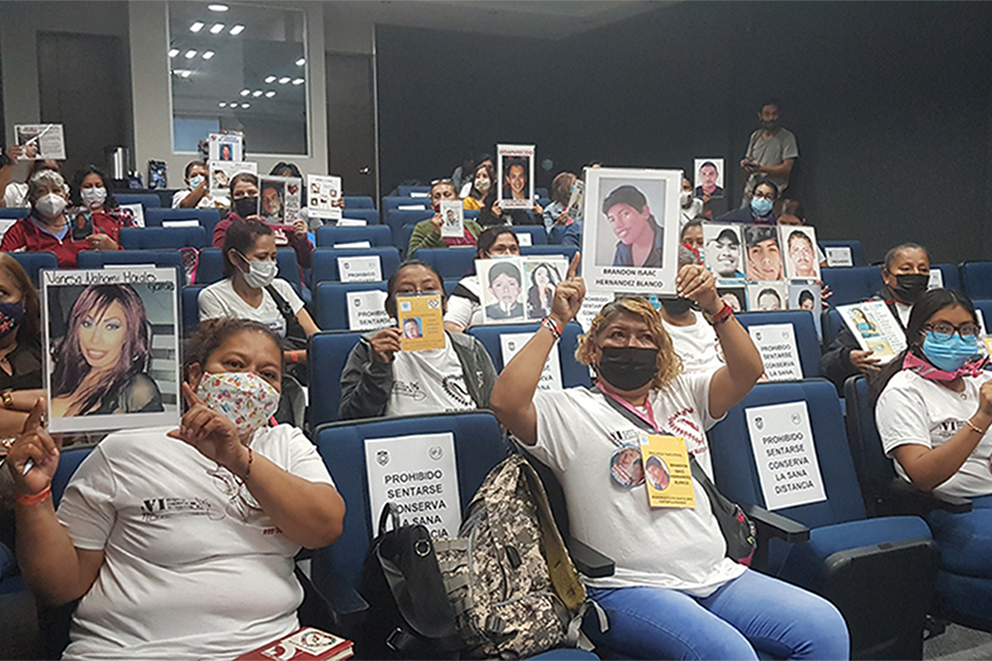

It was after 10 in the morning, a group of 41 people entered the state prosecutor’s office (FGE) in Cuernavaca, the capital of Morelos state. Holding banners and signs, they wore t-shirts with photos of their missing family members on them.

A young man in formal attire told the group to go into an auditorium, where they would project files detailing the information of unidentified bodies on a screen.

These files include bodies that Semefo hasn’t been able to identify, such as those found in the mass graves of Tetelcingo and Jojutla.

Alejandro Cornejo Ramos, an attorney specializing in enforced disappearances, welcomed the families and personally oversaw their search outing.

«Everyone must turn their phones off, no photos either,» he repeated several times before getting started.

The doors closed, and in total darkness, the projection of the identification catalogue began. It consisted of white pages with the FGE’s seal on them, showing photos of the bodies, their belongings, their sex, height, tattoos, and where they were found.

After four hours, a voice questioned the little information they were being granted: the majority of the information sheets had very little information. In some cases, the sheets just read «NA» (no apta), meaning «not suitable.»

An employee condescendingly explained that they had decided not to show certain photos or information so as not to revictimize the families, saying he did so out of respect.

This explanation outraged the families, who are direct victims of these crimes. They explained that the incomplete information denied them «a golden opportunity» to find leads to be able to identify their loved ones.

There are hundreds of unidentified bodies in Semefo’s mortuary refrigerators in Morelos, as well as in Cuautla’s municipal public cemetery.

The families, who have been searching for their family members for years, began to pelt government employees with reasons they should be allowed to see the information.

We are used to seeing these kinds of images, and things that are even worse, with the goal of finding our loved ones.

Woman searching with the Sixth National Brigade

As they explained to the official why it’s important to see all the remains and know every detail, they accused Mr. Cornejo Ramos of scrolling through his social media and ignoring the victims’ needs.

The complaints and anger got worse and worse. Cornejo Ramos tried to deny their accusations, but he was visibly bothered. They had to call a recess.

“The information we were given is incomplete»

As they waited outside the auditorium, one woman stood out: she wore a pink hat, a pink bandana around her neck, and a purple face mask.

In her hands she held a missing person flyer reading «Help me find her.» It showed a photo of Yael Monserrat Uribe Palmeros, 21 years old, who disappeared on July 24, 2020 in Iztapalapa, Mexico City.

Jaquelín Palmeros is Yael’s mother. She’s been looking for her daughter for over a year, and she says that she wears a pink hat to show that she’s looking for a woman who might have been a victim of crimes such as femicide or human trafficking.

She’s a member of the search collective Una Luz en mi Camino (A Light in My Path) and a participant in the Sixth National Search Brigade.

Like most families missing a loved one, she says, she’s dealt with insensitivity, inefficiency, and lack of expertise in police offices.

In her case and many others, Mexico City prosecutors have lost the chain of custody, meaning they’ve misplaced the few hints –including videos– they could have used to find Yael.

Meanwhile, Morelos police have ignored collaboration efforts from Mexico City authorities.

«The car that Yael got into was last known to be in Tlalpan [Mexico City’s largest borough],» she said. «This is why it’s important for Morelos authorities to intervene, but they still haven’t answered.»

Jaquelín found it important to participate in the Brigade and come to the prosecutor’s office. She believes there may be a lot of clues in Morelos.

But all that she had access to in the Morelos prosecutor’s office was incomplete information.

«The information we were given is incomplete… We don’t know how [the authorities] determine the conditions of the bodies they showed us on the sheets. For example, they say that a person has a tattoo, but they don’t say [or show] what the tattoo is,» she said.

Inconsistencies from state prosecutors

Goyita Ortiz has been traveling to FGE offices for 14 years to find her son, Gustavo Alberto de la Cruz Ortiz, who disappeared on March 21, 2007.

Goyita has looked through identification catalogues before. She claims that what the FGE showed them doesn’t compare with the work of prosecutors in Guadalajara, Hidalgo, and Tlaxcala. She says that the other offices have produced many more files and clues.

«We got a lot of information there that’s been very helpful to us,» she said.

The way that the Sixth National Brigade sees it, the way the Morelos prosecution office handles files of the bodies under its domain demonstrates inconsistencies.

Edith Hernández says that she’s seen almost all of the FGE’s catalogue in her search for her brother Israel, who was disappeared and later found in clandestine mass graves in Tetelcingo.

She’s part of the collective Búsqueda de Familiares Regresando a Casa (Search to Bring our Family Members Home) in Morelos. Their members have been present for the disinterments of the bodies found in the mass graves of Tetelcingo and Jojutla.

Edith has seen the identification sheets once and again.

During the Brigade’s second visit, she realized that, although the FGE had agreed to show all of the sheets, they didn’t show the ones corresponding to the mass graves.

A few months ago, some of the bodies were transferred from Semefo to Morelos’ public municipal cemetery. They didn’t show those sheets either.

I asked why they weren’t included, and Cornejo said that he would look into it. But still, in the weeks that followed, they never showed us the sheets from Tetelcingo, Jojutla and those that were transferred from Semefo.

Edith Hernandez

By the time the Brigade’s visit was over, no one had been able to identify a body or obtain clues to help them find their loved ones.

Keeping the faith

Under a blazing sun, dozens of people wait lined up, single file.

Almost all of them are women in blue jeans, red t-shirts and slip-on shoes. All that they brought with them are banners and posters with photos of missing people on them.

They look impatient, as if they’re about to confront something that could change their lives, be it for better or for worse.

They’re on the second floor of the Morelos Correctional Center in the community of Atlacholoaya, Xochitepec.

They’re waiting for police to give them access to the male and female wards as part of the Sixth National Search Brigade’s team that is searching for the disappeared who may still be alive.

Evelia is at the front of the line. Suddenly, she realizes that she left her cream-colored rosary in her pants pocket.

She nervously looks for someone that can hold the rosary for her while she’s inside the building. Otherwise, it could be taken from her in the security screening line.

Her eyes glimmer as she finally finds someone who’s up for the task, and asks them to hold it for her.

«This rosary means a lot to me,» she says in a shy voice, cautiously handing it to them.

It’s Evelia’s first search outing, her daughter gave her the rosary to protect her.

She’s aware of the risk she’s taking, but she says she’ll search «wherever possible» to find her son Erick Jesús Pérez Santibañes, who was disappeared on May 16, 2019 in Morelos.

She reveals that she’s a devout Catholic and a firm believer in God. This is why, as she prepared to leave for the brigade, she brought the rosary to her priest to have him bless it.

Evelia is part of the Morelos collective Regresando a Casa (Coming Home), which is why she joined the Brigade.

She joined the group that was going to visit prisons, a place she’s never been before. This added to her nervousness.

When you go in, you’re just hoping that someone on the inside can give you leads, something to help you find, in my case, my child.

Evelia

She didn’t find anything this time; not a single sign that anyone knew anything about her son, who was a taxi driver and a salesman.

However, she’s keeping her faith. «I believe in God and I’m sure that I’ll find my son soon.»

Evelia got her rosary back towards the end of the search outing, and her fear of losing it dissipated.

«I feel totally unprotected without my rosary,» she said.

«I know your pain»

The search group of almost 30 people didn’t leave completely empty-handed that afternoon: the imprisoned men and women gave them information that could help locate three women who disappeared in Veracruz.

There was an emotional moment in the female ward when the imprisoned women, dressed in beige and yellow, expressed their solidarity and promised to pray for the families missing their loved ones.

A woman who’s been imprisoned for years stepped up and expressed that she understood the pain of the mothers, daughters and sisters who traverse Morelos in search of their family members.

She told us, ‘I know your pain. They separated me from my daughter when I got here. Child protective services kept her in a shelter for a long time, and they threw her out when she turned 18. She went missing after that. The difference between me and you all is that you’re out looking, and I can’t do that from here.’ Then she asked us to help look for her.

Angelica Rodríguez Monroy, host of Morelos’ National Search Brigade

Angelica is the mother of Viridiana Morales, a young woman who disappeared nine years ago.

As a participant in the Brigade, she visited district prisons in Cuautla, Jojutla, Jonacatepec, and Atlacholoaya. She’s also been blocked by prison authorities.

Authorities give them access, but in Morelos, unlike other states’ facilities, «there wasn’t as much opportunity to interact,» Angelica says.

She adds that this is «mostly due to the lack of knowledge of how these brigades operate, or maybe because somebody wants to hide information.»

We know that one of them could be the culprit

According to the 2020 Social Reintegration Assessment published by the Human Rights Commission of Morelos, overcrowding and staff shortages in prisons mean there are ideal conditions for rule by criminal organizations.

«[Prison] authorities have such a tight grip on the inmates that they’re distant to us, they don’t want to participate, and some even mock [the families],» says María Asunción Estrada Flores, who is searching for her son Ernesto Hernández Estrada, who disappeared on September 13, 2016.

For instance, during the first prison visit in Jojutla, out of the 500 inmates, only 130 willingly participated, 105 men and 25 women.

«The officers kept their guns at hand and watched their every movement. They took pictures with their phones the whole time,» Alejandra Rodríguez said.

On a second visit to the same facility, after news articles detailing the families’ complaints had been published, prison authorities changed the dynamic. The environment was still hostile, now on the part of the inmates as well.

«They let us bring in cards and pens so that they could write us messages, any information to help us find the people in our photos,» said Yadira Mercado, sister of Jessica Mercado, a young woman who disappeared in September of 2012 in the municipality of Xochipetec and was later found in the mass grave in Tetelcingo.

She added that «it didn’t turn out that way, they just left us messages of solidarity and support. They said they would pray for us and our missing loved ones.»

The excessive surveillance by prison officials continued.

Yadira, who managed to find her sister and give her a dignified burial, explained that she joined the Brigade to help other families find their family members. She knows how it feels to not know where they are.

This is why she was outraged by the inmates’ insensitivity during the visit.

«Some of them came in with a really arrogant attitude,» she recalls, visibly upset. «They looked at us mockingly, they didn’t even stop to look at our photos.»

Eunice Pelcastre Badillo is the mother of Guillermo David Ramírez Pelcastre, who disappeared on September 22, 2017 in Ecatepec, Mexico State.

She says that it was really frustrating to go inside the prison, «because we know that one of them could be the person responsible for the disappearance of our missing family members.»

It was obvious to the members of the Brigade that the prison authorities or a third party ordered the inmates to behave in this way.

Family members of the disappeared assume that there’s a hidden system of obfuscation in Morelos to stop them from getting information.

During the prison visits, two incarcerated people asked for support in searching for family members whom they, being imprisoned, can’t search for themselves.

María Asunción Estrada Flores is searching for her son Ernesto Hernández Estrada, who disappeared on September 13, 2016. She said that they’ve gotten access to maximum-security prisons, and that they’ve had more interaction with the inmates there. This is how they’ve been able to obtain valuable information.

«Today was a farce. The authorities here tried to change things and control the information,» she added.

Preliminary report from the National Search Brigade

On Friday October 15th, the Sixth National Brigade shared their preliminary report in front of the Memorial to Victims at the front entrance of the government palace in Cuernavaca, Morelos.

It stated that they had discovered 10 clandestine burial sites in Cuautla and Yecapixtla.

The first finding was in the municipality of Cuautla, where the Brigade had previously carried out searches.

In the second week, they searched in a sand mine in Mixtlalcingo, Yecapixtla.

There, the families found eight burial sites, three of which are being processed by Morelos’ state prosecutors. There was a ninth finding in Mixtlalcingo on October 23rd.

The last finding was close to a work site in Yecapixtla, in a building that had been used as a safe house.

Although the area had already been combed and searched by state prosecutors, the findings showed irregularities, as state authorities «hadn’t correctly removed fragments and evidence» of human remains, the report stated.

On October 23rd, a search group began work in the municipality of Amacuzac, one of Morelos’ most violent areas with a high incidence of organized crime.

According to official reports, the group «Los Rojos» operates in Amacuzac. The group has been led for years by Santiago «N».

Estrella Pedroza is a freelance reporter and a member of Reporter@s Morelos for the professionalization and dignification of journalism.

Click here to join Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona