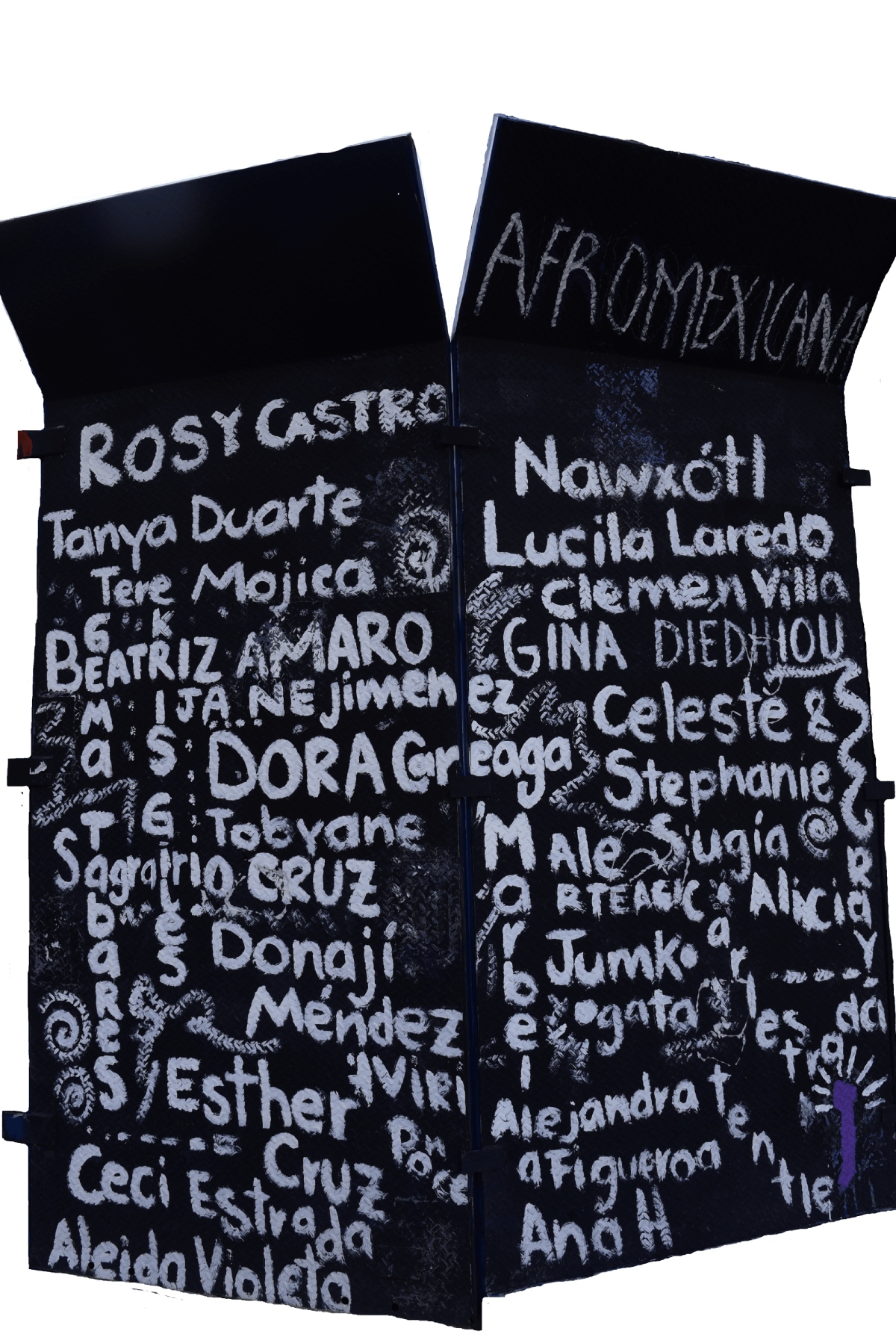

The names of women who have fought and organized as part of all different struggles surround the base upon which a statue of Christopher Columbus once stood. Even though México’s National Human Rights Commission has recommended the transformed monument remain as is, the government of Mexico City has plans to remove it.

Text and photos by María Ruiz, originally published on October 7, 2022.

MÉXICO CITY—On September 25, 2021, women from various struggles took over the pedestal in a traffic circle on Reforma Avenue, where a statue of Christopher Columbus once stood.

On the fencing around the statue, which had been installed by the México City government, they wrote the names of women who have struggled in various causes throughout history. They hung a clothesline where women could hang written accounts of being assaulted and by whom (tendedero), in the spirit of a performance by Mónica Mayer.

“The roundabout, the garden and the protest clothesline are things we have created, they were made so that we never forget the women who have had to take to the streets for justice and truth, the women who have been killed in their fight, to keep the constant violations of our human rights, the unacceptable lack of justice and the danger that women and girls live in México present every day,” according to a poster in the space.

The Monument to Women in Struggle (Glorieta de las Mujeres que Luchan) is in a strategic location, one of the most iconic and touristy places in México City. Over the past years, Reforma Avenue has been transformed into the “pathway of memory,” as anti-monuments recalling rights violations have been put up all along the boulevard.

The takeover of the monument was carried out by women searching for the disappeared who belong to the National Connection Network, mothers of victims of femicide, water defenders, survivors of acid attacks, Triqui, Otomí and Nahua women, and their mothers of the disappeared students from Ayotzinapa.

The occupation took place in a context in which México City officials announced they would remove the statue of Columbus, a colonialist figure, and that it would be replaced by a statue by artist Pedro Reyes. His statue was called Tlali, and it was the subject of complaints due to the way he represented the body of an Indigenous woman.

Tlali never made it to the top of the pedestal, due to the polemics surrounding it. Instead, the city is planning to place a replica of “The young lady of Amajac,” an ancient statue recently found in the state of Veracruz. It is believed she was a governing woman from the Huasteca elite. The problem is that the pedestal where they plan to place the statue has been occupied by the figure of a woman that seeks to represent the struggle of many women.

“The state has a policy of selective memory. It chooses where and what events are remembered, because that’s what is convenient to it publicly. One of the ways memory is used now is to support the narrative of [the current government, which refers to itself as the Fourth Transformation]” according to the women responsible for the space, who have asked to remain anonymous in order to maintain the collective character of the Broad Front of Women in Struggle.

Since the very first day they took over the space, their monument has been under threat. The day after it was set up, the México City government erased the names they’d painted on the fence, but they returned and painted the fence again.

Since the monument was taken over, the México City government began to feed a false conflict between women who took over the pedestal and Indigenous women who live in the city. That’s why on Friday, organized women wrote a letter clarifying that the monument was created by diverse women and that it is collectively theirs, representing all their struggles.

In the face of a discourse created and fed by the state, in which there is a supposed dispute between “feminists” and Indigenous women for the space, the women organizing the anti-monument have responded to being called “the bad feminists who graffitti and burn things.”

“This exercise (The Monument to Woman) is a response. We’re not against direct action, but we understand that it can be a trap, and this is a creative and illuminating response to say: we can [struggle] in many ways,” it reads.

They have also made a complaint to the Human Rights Commission of México City. The Women’s Front mentions the lack of public consultation on the statue that will be installed, which Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum promised; the removal of the names from the fences last year; the imposition of the replica of the Young Lady from Amajac; the destruction of the (anti) monument for the victims of machista violence; and structural damages to the Garden of Memory.

In their complaint, the women from the Front say their right to memory has been violated. That right is protected in Article 5 of the Political Constitution of México City, as part of the right of all victims to have access to reparations for damages against them.

The women working to protect the space are asking people to come down to the statue and join them, especially given the news that the new statue may be put up in the coming weeks. They are publishing updates to Instagram.

They have also said they will continue to resist. “We are going to continue to fight and struggle. What we are fighting for is just, and it is important: the fair treatment of victims.”

María Fernanda Ruiz is always an outsider, audiovisual is her jam, and journalism is the path through which she understands and questions the world.

Click here to sign up for Pie de Página’s bi-weekly English newsletter.

Ayúdanos a sostener un periodismo ético y responsable, que sirva para construir mejores sociedades. Patrocina una historia y forma parte de nuestra comunidad.

Dona